Master Thieves (7 page)

Authors: Stephen Kurkjian

In a matter of seconds the shorter man had steered Abath to a nearby wall. He forced him to spread his legs and slapped a pair of handcuffs on him.

Wait a minute,

Abath thought to himself.

He didn't even frisk me.

It was at that moment Abath knew the two men he'd let into the museum weren't police officers. They hadn't come to investigate a disturbance. They were there to rob the place, and he had allowed it to happen.

Abath had his face to the wall when Hestand walked into the room and heard him ask why he was being arrested. Out of the corner of his eye he could see that the taller of the two men had turned Hestand around and was putting handcuffs on him.

“This is a robbery, gentlemen,” one of the men said almost matter-of-factly. “Don't give us any problems, and you won't get hurt.”

“Don't worry,” Abath responded sharply. “They don't pay me enough to get hurt.”

The thieves quickly wrapped both men in large strips of the duct tape they'd brought in with them, covering even the watchmen's heads and eyes. Then, without asking how to get there, the two men led the hapless guards to the basement. They seated Hestand beside an unused sink, which he was then handcuffed to. Abath was led down a long, narrow corridor to a workbench, where the intruders seated and handcuffed him as well.

After relieving them of their wallets, the thieves told each man, “We know where you live now. Do as we tell you and no harm will come to you. If you don't tell them anything, you'll get a reward from us in about a year.”

You people have no interest in doing anything for me now or a year from now,

Abath thought to himself, as he tried to relax as

best he could, getting accustomed to being handcuffed to the sink with the duct tape still covering his eyes and face.

While the thieves went about wreaking havoc inside the museum, Abath's mental state went from boredom to terror. He knew these guys were serious and that they certainly didn't intend to get caught. With that in mind, Abath figured they'd likely set fire to the place before they left, and he began to panic. He began to sing, almost chant, Bob Dylan's “I Shall Be Released” over and over again: “So I remember every face, of every man who put me here.”

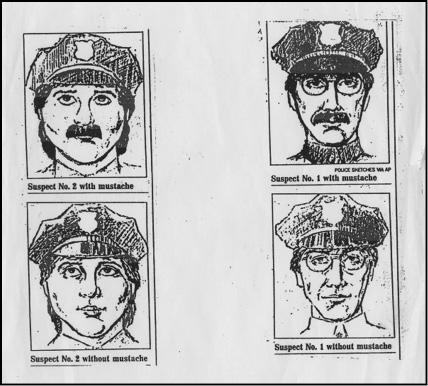

Even so, when Boston police later asked him what the men looked like, Abath could provide only the sketchiest of details. One of the thieves appeared to be in his late thirties. About five feet, nine inches, slim with gold wire glasses and a mustache, though that was probably fake. The other looked to be in his early thirties, six feet tall and heavier, with chubby cheeks. He also sported a mustache.

“That's awful!” Abath blurted out when the police showed him the artist's composite drawing based on the description he'd provided. In the ensuing years all he could remember was that one of the men looked like Colonel Klink from the popular late â60s television show

Hogan's Heroes.

But sitting there handcuffed, helpless while the intruders were doing God knows what, all Abath could do was cycle through his mind, wondering if he had ever seen either of the pair before. Maybe he'd spoken to them in a bar or some other chance encounter and told the thieves about the museum's miserable security system. Or maybe it was because so many people had worked the night shift over the years and knew the terrible secret that there was only one alarm to alert the outside world of a problem inside the museum and that the next shift didn't start until 6:30 the next morning, so there was no one to check on things once Abath and Hestand had been subdued.

The FBI and Boston police artist drew sketches of the two robbers following the heist using recollections of the two night watchmen who were on duty. However, more recently the security officer who spent the most time with the thieves dismissed the accuracy of the images.

It could have been anybody,

Abath thought. How many times had he and his roommatesâseveral of whom also worked security at the Gardnerâcomplained to each other about the lousy security the museum had in place?

Abath had probably made such claims in his own house, which was less than two blocks away from an antiques store run by a suspicious character with mob ties. William Youngworth, the store owner, was a friend of several members of the Rossetti gang, and would draw much attention to himself in 1997 by claiming he could facilitate the return of the stolen artwork. Had Abath's complaintsâwhich suddenly seemed to him to be very conspicuous, and perhaps even a threat to his lifeâsomehow been overheard by Youngworth? Or perhaps Abath shot off his mouth about the museum's security lapses at the Channel, a rock club Abath remembers visiting, or one of the seedier ones where Ukiah played in Brighton or

other Boston neighborhoods, some of which had mob connections of varying degrees.

All these thoughts tumbled through Abath's mind as he lay handcuffed and covered in duct tape in the museum basement.

It had taken the thieves about fifteen minutes to subdue Abath and Hestand. It was 1:35

a.m.

While Abath sat imagining these conspiracies, the thieves were on their way, moving among the Gardner's hallowed galleries.

Strangely, their first footsteps weren't picked up on the museum's motion detector until they made their way to the Dutch Room on the second floor at 1:48. The pair may have waited to make sure their presence inside the museum hadn't been detected and that no emergency calls had been made to the Boston PD. Most important, they made sure no cruisers had been sent to investigate.

Surely they also had knowledge about the museum's security system and layout. They knew they had to get Abath away from the panic button located within his reach at the security desk. They knew how to get to the museum's basement and where to hold Abath and Hestand. Now they knew police had no way of knowing that the heist was under way.

The Gardner was theirs. They could have spent the entire night inside.

“Someone is in the Dutch Room. Investigate immediately.” At 1:51

a.m.

the motion detector on the first floor typed out that message, but of course no one was there to see it. The two intruders had made their way up the Gardner's marble steps to the second floor and had entered the gallery where some of Mrs. Gardner's richest treasures were kept: three large Rembrandts and Vermeer's

The Concert.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

was the most valuable of the Rembrandts that Mrs. Gardner had purchased for her museum. The only seascape the master is known to have done, the painting is a dramatic representation of the story told in

Luke's chapter in the New Testament of Christ calming a violent storm that has so frightened his disciples they awoke him. Mrs. Gardner purchased the painting from a London gallery in 1920 after learning of its availability from Bernard Berenson, the young Harvard-educated art specialist she'd hired to locate masterpieces to fill the galleries she envisioned sharing with the world.

The painting itself was large, at more than five feet in length and four feet in width, and even bigger encased in a golden frame. Hardly master thieves, the intruders pulled the majestic Rembrandt from where it hung on the far wall of the gallery and threw it to the marbled floor, shattering the glass in the huge frame. With its canvas exposed, they cut the painting, which had been completed in 1633, sharply from its wooden backing.

As they did, a small device suddenly began to screech from a socket on a nearby wall. The size of a night light, the device had been installed to warn the Dutch Room gallery guard that a patron had gotten too close to the canvas, most often to point out that Rembrandt had etched an image of himself among the disciples on the boat. The sound likely shocked the pair, and one of them hunted it down and smashed it to pieces.

Again there was silence.

They were just as brutal with the second Rembrandt,

A Lady and Gentleman in Black.

The two broke its enormous glass frame, cutting it from its wooden backing, too. Although not as dramatic a sight as

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee,

the painting originally included a young boy waving a wand or stick to the lady's right. But the figure was removed when the work was completed in 1633.

The thieves then moved on to a third large Rembrandt, a self-portrait of the Dutch master. Deciding it was too large to transport, the pair left it leaning against a cabinet rather than making off with it. While that self-portrait may have been too

large to transport, the thieves did grab a postage stampâsize portrait Rembrandt had etched of himself from the table beneath it. Remarkably, it was the second time the work had been snatched.

In the only other theft known to have taken place at the museum, the self-portrait had been stolen in a daytime heist in 1970 when a patron diverted a guard's attention by throwing a bag filled with lightbulbs onto the floor, making a loud crash, and an accomplice snatched the self-portrait from its stand. Although no one was ever arrested in the theft, the drawing was returned to the museum several months later by an art dealer who told authorities that an unknown person had come in to sell it to him, but when the gallery noticed on its back a stamp that showed it belonged to the Gardner, he called the museum immediately to report its whereabouts.

Now, two decades later, a far bigger robbery was taking place. The thieves then moved to a small table on the right side of the gallery and concentrated on the two paintings atop it: Vermeer's

The Concert

and a painting that had long been regarded as being by Rembrandt, the pastoral scene

Landscape with an Obelisk

.

The Concert

was by far the most valuable of the thirteen pieces ultimately taken that night. Only 28½ by 25½ inches, the painting could easily bring $250 million at auction, more than $100 million higher than the 2013 sale of Francis Bacon's triptych,

Three Studies of Lucian Freud,

by Christie's New York. Vermeer's masterwork fully displays his uncanny ability to capture light and dark in great detail.

The Concert

shows a man and two women playing music, with the late-day light softly entering the room through a window on the left, and casting a different glow to every inch of the oriental rug lying atop a table and every fold of the women's dresses. Its brilliant whites capture the small strands of pearls each woman wears.

Without regard for any of this, the thieves removed the great work from its golden frame. Then they did the same to

Landscape with an Obelisk,

which rested at the other end of the table in the Gardner's Dutch Room. It has long mystified many as to why this work was among the pieces the thieves took, as it had long before been dismissed as a painting by Rembrandt.

It's also a mystery as to why the thieves decided to take the final piece they did from the Dutch Room: a Chinese beaker from the Shang era. Called a

ku,

the foot-tall vase was one of the oldest artifacts in the museum, dating back to 1200 BC, with its worth estimated at several thousand dollars.

Upon climbing down, frustrated by their failure, they turned their ire to two frames in a nearby case that contained five sketches by Edgar Degas. Smashing both frames, they tore the sketches from them. Whether the thieves were interested in the horseracing motif of the sketches or angry at their inability to free the Napoleonic banner, the combined value of the Degas sketches was less than $100,000.

The thieves spent sixteen minutes inside the Dutch Room, mostly dashing back and forth from it to the Short Gallery on the other end of the second floor. There, although a priceless Michelangelo drawing was nearby, the thieves concentrated their attention on a Napoleonic banner. They labored to get the banner out of the glass-and-wood frame that encased it on a four-foot flagpole at the far end of the gallery. The frame was fastened together by six tiny screws, and the thieves removed them, dropping each to the floor below. The task proved too laborious, however, and the pair finally abandoned the job. But before they jumped down from their perch, they snatched the gold-plated eagleâcalled a finialâthat rested atop the flagpole.

“To me it's the biggest mystery in the entire case,” says Anthony Amore, the security director of the museum, who has long analyzed every move the thieves made, baffled by how they decided what to take. “Why did they take what they did, and leave what they did? It just makes no sense to me.”

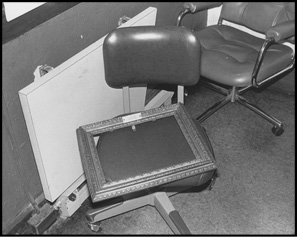

Crime scene photos taken after the theft.

Â

The havoc of the theft is shown in the second-floor Dutch Room, where the greatest masterpieces were taken, leaving behind broken frames and shattered glass.

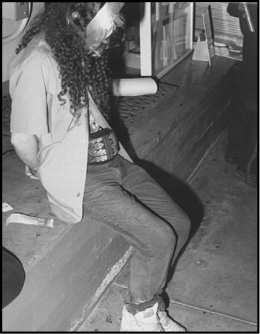

Richard Abath, who made the grievous error of allowing the thieves into the museum.

The frame of Eduard Manet's

Chez Tortoni

, taken from the first floor Blue Room, was left on the chair of the museum's security chief.

Five prints by Edgar Degas were broken from frames that hung in the Short Gallery.