Mary McCarthy's Collected Memoirs: Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, How I Grew, and Intellectual Memoirs (68 page)

Authors: Mary McCarthy

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Memoirs, #Professionals & Academics, #Journalists, #Specific Groups, #Women

I was conscious, naturally, of seeing my girlhood wishes—all those mornings spent immersed in

Vogue

—come improbably true, and it delighted me to be staying not merely with rich society people but with old-family patricians unable to afford central heating. And it was a strange coincidence—the return of the repressed?—that my old Seminary friend the very fast Helen Ford, from Montana, should turn up close to Rokeby, in the very same neighborhood, indeed just down the road, near the old country town of Red Hook, as a widow and running a chocolate factory painted the color of a Hershey bar, with a house to match next door. She had married the son of the popular author James Oliver Curwood, whom she met on a world cruise of “the Floating University”; he died, leaving her a chocolate business, originally located in Barrytown and named Baker’s, but which was not the same as

the

Baker’s. After going over from college, once, for dinner, I did not pursue the relationship and was startled years later to find that Maddie knew about her and had been curious to meet her.

In the sitting-room of the Tower, Clover had painted a mural of us all in the nude, which produced the inevitable scandal even though the likenesses were no closer to photographic realism than “Les demoiselles d’Avignon” by Picasso. It was felt to be very shocking that we invited men to tea in the presence, so to speak, of ourselves in the altogether. That was the only scandal. Among us, there was occasional dissension as to who should wash the bathtub—we had one for eight people. Otherwise there were no special incidents unless we made the mistake of playing Truth or Consequences.

Yet my relation with the group underwent a change. Extraordinary to relate, they became possessive about me. Besides Bishop and Frani, I had a lot of other friends—Betsy Strong, Fran Rotter, Martha McGahan, Rosemary Paris (who had played Perdita to my Leontes and later married Arthur Mizener)—and the group did not like it if I ate dinner at their tables or went off campus with them to the Popover Shop or the Lodge. Or down to Signor Bruno’s to drink wine out of coffee cups with the

Con Spirito

board, though this was usually not at meal-times and it was the dining-room—an empty place at table—that bothered them most. I was unaware of this and perhaps should have been flattered when a delegation came to me to suggest that I eat a bit more often with my own group. But actually, I was depressed by the clannishness of their behavior, typical, I now know, of society people, who are great stickers-together.

It was mid-June the morning we graduated, and I fainted in the chapel from the heat. Afterwards Frani’s parents took several of us to lunch at the Silver Swan. My grandparents had not come on for the occasion, to hear me get my

cum laude

(no

magna

);

they sent me the money the trip would have cost them. That was my graduation present, and perhaps it was just as well that they were spared Clover’s mural. Besides that, my grandfather sent me a check for what they might have given me for a trip to Europe, such as Frani was getting from her parents—

that

was a wedding present, he wrote. Yes, the decision had eventually been made. We had even sublet an apartment, furnished, on East 52nd Street, from Miss Sandison’s sister, Lois Howland, who taught Latin at Chapin. Feeling the depression, she and her husband were moving down to the National Arts Club and leaving us their very nice things. It was over a “cordial shop” (liquor store) and next to a dry-cleaner’s; at the end of the summer, when the Howlands’ lease ran out, we would have to find a place of our own.

We spent the night in the apartment, then took a taxi down to St. George’s Church, on Stuyvesant Square. We had already had an interview with the curate, and it was exactly one week after Commencement and my twenty-first birthday when we “stood up” together in the chapel. I had a beige dress and a large black silk hat with a wreath of daisies. Most of the group were present; Frani had already sailed for Fontainebleau to study music, and Bishop, I think, was not there either. We had a one-night honeymoon at an inn in Briarcliff, and there all of a sudden I had an attack of panic. This may have had something to do with an applejack punch we served at the reception or with the disturbing proximity of Scarborough, suffused with bad memories of the summer before. As we climbed into the big bed, I knew, too late, that I had

done the wrong thing.

To marry a man without loving him, which was what I had just done, not really perceiving it, was a wicked action, I saw. Stiff with remorse and terror, I lay under the thin blanket through a good part of the night; as far as I could tell from what seemed a measureless distance, my untroubled mate was sleeping.

Image Gallery

Tess and her daughter, Mary McCarthy, one and a half months old, Aug. 10, 1912, Seattle

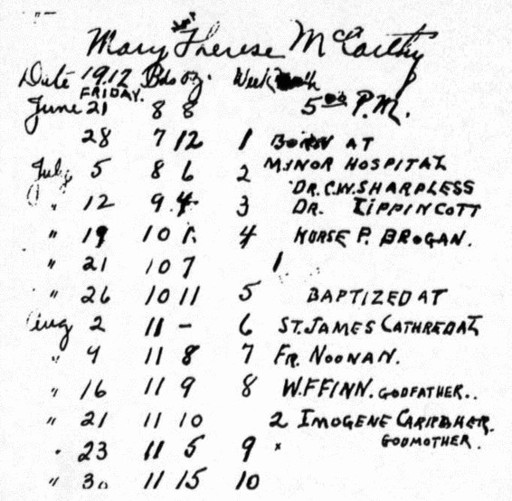

From Roy’s desk calendar

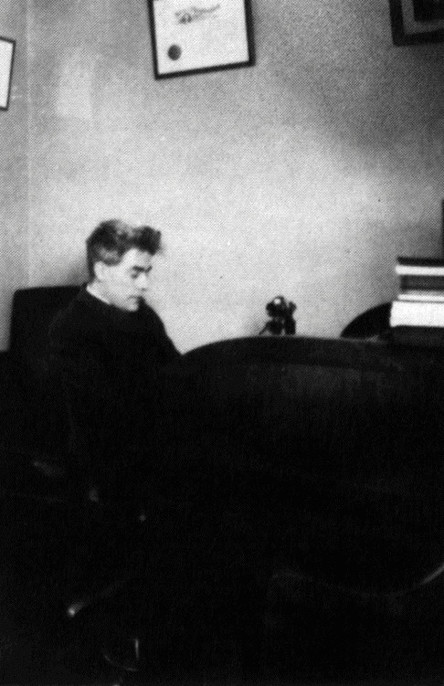

Roy in his office, probably in the Hoge Building, Seattle, around 1914

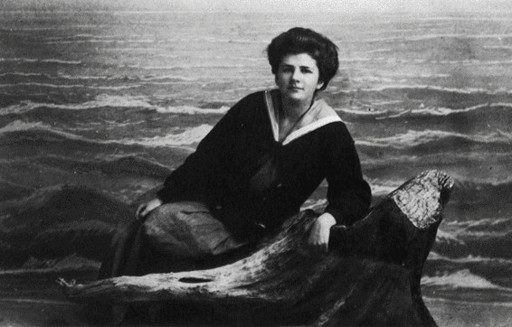

Tess against photographer’s ocean, 1910, The Breakers, Oregon

Tess in her engagement photo

Harold Preston

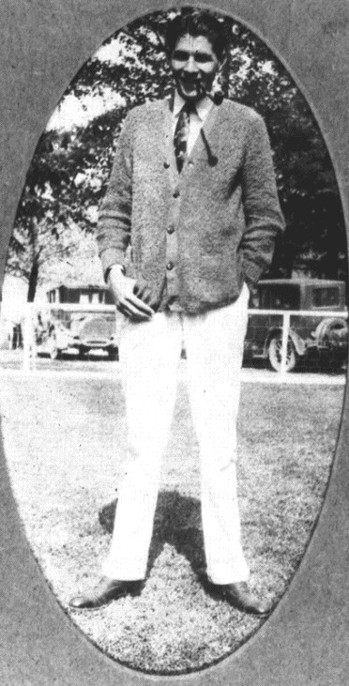

Roy McCarthy

Four generations, Seattle, around 1916: Mary, Simon Manly Preston (great-grandfather), Kevin, Harold Preston (grandfather), Tess with Preston on her lap