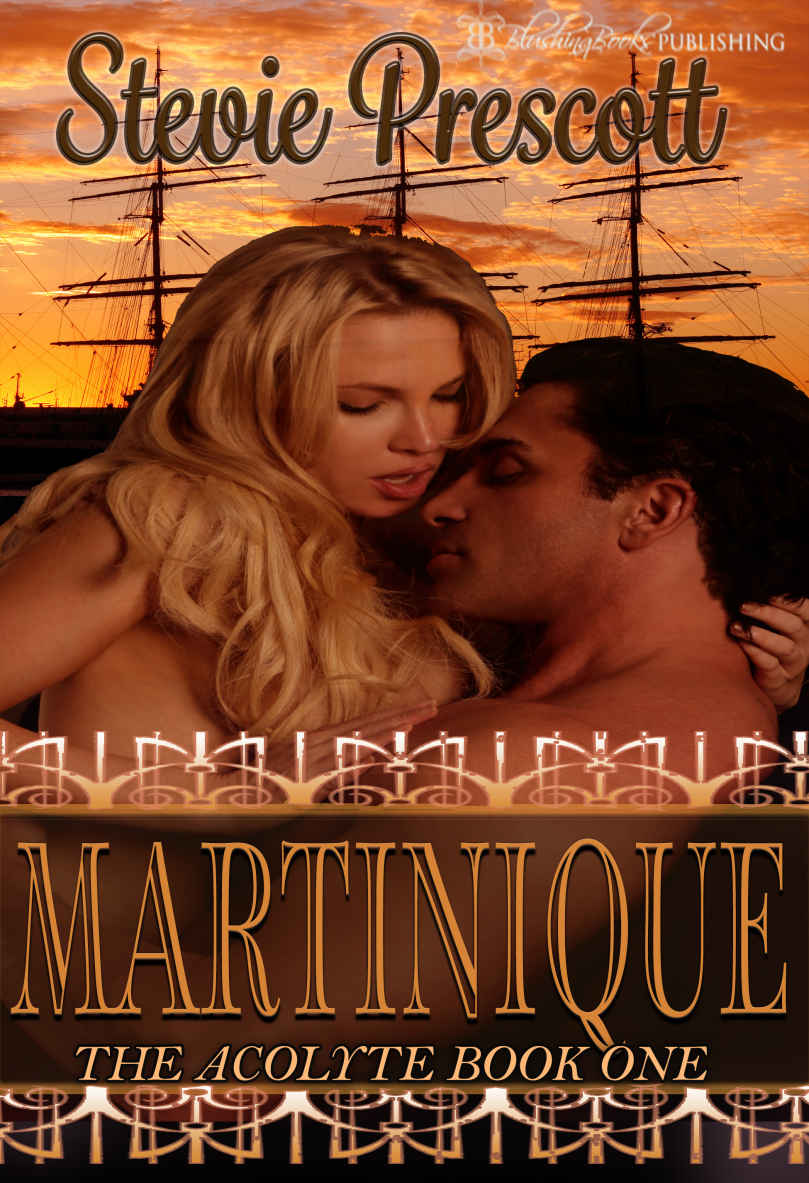

Martinique (The Acolyte Book 1)

Read Martinique (The Acolyte Book 1) Online

Authors: Stevie Prescott

Martinique

The Acolyte, Book One

By

Stevie Prescott

©2015 by Blushing Books® and Stevie Prescott

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Blushing Books®,

a subsidiary of

ABCD Graphics and Design

977 Seminole Trail #233

Charlottesville, VA 22901

The trademark Blushing Books®

is registered in the US Patent and Trademark Office.

Prescott, Stevie

Martinique

eBook ISBN:

978-1-62750-004-1

Cover Design by ABCD Graphics & Design

This book is intended for

adults only

. Spanking and other sexual activities represented in this book are fantasies only, intended for adults. Nothing in this book should be interpreted as Blushing Books' or the Author's advocating any non-consensual spanking activity or the spanking of minors.

Table of Contents:

I am an historian. You would not have heard of me. I once wrote a book on the life of Samuel Pepys. I live in an ivory tower with others like myself. Academics. Christ, I've come to despise the word.

Even so, I've never lost that feeling of awe when I lay hands on the past, my fingertips sliding into the furrows of an ancient marble balustrade, slim channels left by centuries of other hands that gripped it. But my work has been built on what others have found. I'd never uncovered an artifact lost to the world of men. Or in this case, the world of women.

My marriage was in a state of cease-fire when my restless husband found a house in upstate New York, once a hunting lodge for a robber baron's mansion. A great little fixer-upper, if one were so inclined. I'm not. But it gave us something to argue about besides who hid the remote.

Though I'm not handy, I was working in the attic, which was to be done over into my office, when I found something hidden in a cubbyhole of the crumbling chimney bricks. A great little fixer-upper for black widows. I screwed my courage to the sticking place and snatched it out, a packet wrapped in old butcher's paper.

It was a set of three bound journals, about mid-nineteenth century. Despite my profession, I wasn't particularly excited. People were once great keepers of journals, and I'd seen hundreds. Most were incredibly tedious, births and deaths, church socials, lodge meetings and household accounts. Still I looked them over, intrigued by the stark headings on the facing page of each volume: Martinique, the Seraglio, and America.

This was not the household accounts. I'd retrieved something remarkable.

"Left-handed literature," Rousseau called it, the right busy bringing relief to the overheated reader. Hypocritical bastard. He wrote enough of it himself. But this was more, far more than that. I didn't stop until I'd finished them all, even though it took time to adjust to the flagrantly feminine handwriting, blobby pen nub dipped in ink. Not to mention the imaginative spelling and sentences that finished in another zip code.

None of which ruined the magic of the story. And what a story! These were the journals of a remarkable woman, a woman of wit and indomitable spirit. A woman far, far beyond her time. Perhaps beyond my own.

I was determined to put it before the public, the unexpurgated life of Lady Létice Marie de Saint Juste McClain, as I think she intended. I edited it, but tried to keep the archaic feel, and more important, all her observations on the human animal, even if they shocked our modern, politically-correct sensibilities. I think a part of her strength, her defiance of convention, seeped into me.

And so, unexpectedly, I've had a part in uncovering a piece of history. I hope that Létice, wherever she is, feels I've done right by her.

My first distinct memory of childhood was the great watchword of Apollo, fearfully emblazoned in black letters of wrought iron above the gate of the Creole cemetery where, one by one, my family was laid to rest. "He who enters here, know thyself." Admitting, even embracing the truth of my own nature became the trial of my existence, a trial over which I have prevailed, finding acceptance.

It is, perhaps, a revelation I should have taken with me, past that gateway and into my own grave. Yet I have determined to chronicle the remarkable events of my life, for it was a wide and turbulent sea that carried me to this safe harbor. I want, not merely to indulge my own pleasure in reliving them, but to record them, without shame or pretense, and with no recourse to the rank absurdity of euphemism. Within these pages a cock is a cock, not a "machine," and a fuck is a fuck, not a "transaction," as in such outdated but still "scandalous" works as Mr. Cleland's

Fanny Hill

, wherein, on occasion, it's uncertain precisely what is happening, garden party or outright rape.

Such candor requires courage, for I know my own. The Age of Enlightenment is past, "enlightenment" being so often a code word for the libertine, to free Mankind from the shackles of prudery and orthodoxy. The pendulum is swinging, backwards, away from the sheer and clinging Grecian gowns of my youth, and the beauties of the Court with their rouged nipples clearly visible beneath. A New Age has dawned, or so we're told, an age of Romance, "romance" being a code for courtly love from afar, love without juice, without sweat, without passion or pain. Every season of fashion brings another layer of petticoat. Propriety is god, Hypocrisy his willing handmaiden, the reason I've taken care none should know the true identity of the woman who writes these words, if only to protect the one whose life and happiness is dearer to me than my own.

As I sit in my elegant drawing room far above Fifth Avenue, pouring from a polished silver pot, it occurs to me how enviously safe is now my position, as the wife of one of the most powerful men of this city, and indeed of this clamorous and prosperous new nation. Though none should suppose I have subdued my true nature in exchange for the bloodless gratification of money or place.

For from that feverish night I met my husband,

la nuit d'amour fou

, a night of madness, I felt that incredible pull, like a lodestone, the magnetism of like unto like. At first sight, despite the daunting breadth and height of the man, he seemed somehow an innocent, younger even than his years. But then he turned from his pose of virtuous decorum, tilting his head with its strong, square lines, fixing on me the sapphire eyes, darkened by thick lashes any woman would covet, and I felt it, with no word spoken. I was born in the Indies, and I knew what was hidden in the tall cane before me; a viper, eyes hooded, body coiled, poised to strike.

An apt metaphor, considering what was not very well hidden by his cutaway coat and tight breeches. Long before the dawn, I was in the arms of a gamesman of wild imagination and inexhaustible variety. I was, in fact, tied down under him before the clock chimed midnight. As the days unfolded, I began to wonder if I would ever see that massive serpent in a fallen state, nesting in exhaustion within the lush, dark hair. After so long a search, I'd found my Master, and he had found a more than willing Acolyte.

So, I will not endanger that propriety he wears in daylight, in order to safeguard the pleasures of the night, the reason for the satiated, contemplative smile I can feel on my face as I sip at the rich chocolate from Brazil, pen in hand.

I lay no claim to altruism, and certainly not to nobility of character. Yet I cannot deny the other reason I confess my life, apart from self-indulgence. It is for the daughters of this Age, the ones beginning their own journey. Kept unsullied like a porcelain in a glass cabinet, shamed by their own desires, concealing a headstrong nature behind a carefully-crafted façade of wide-eyed stupidity drilled into them like a catechism. Young women who have no awareness of the power they hold within the hands they've been told are weak. The power to rise, and the courage to fall. And the strength to rise again.

I suppose I was something of a Romantic as a child, though in truth I've always possessed a ruthlessly pragmatic nature that early reared its head. For this was the self that I would discover on my journey, the blinding pleasure I so often found when I yielded my own headstrong will to an even more powerful one. Of course, a prisoner is a prisoner, and must endure whatever comes at the behest of her turnkey, no less than some poor beast in a bridle, and I cannot say it always resulted in bliss. But the need was there, from the start, waiting for the man who could strike the flint to the fire.

Yet, how could I not be something of the Romantic, when I am a child of the Indies? The pearl of the Indies, Martinique, to the windward, a place of lush greenery and vibrant blooms, waterfalls over rocky gorges, azure seas and beauty beyond the description of a mortal tongue. A place of heat. One of our favorite foods on the island was called a plantain, and like so much that was good, was brought to us out of the slave quarters, the fruit beneath the tough, greenish-brown skin steamed or fried. It was popularly believed that only on Martinique did the long plantains grow upward, stiff and erect, rather than hanging sadly down in their heavy bunches, and that this quirk of nature was a tribute from the gods of the trade winds paid to the lustful men of those shores.

Although I've discovered that all God's creatures have a talent of some sort, for music or business or science, it was difficult at first to face my own, since I have possessed a talent for lust from a young age, a proclivity that has only grown stronger with the passing years. I pleasured myself for the first time at nine or ten, even before the onset of my first menses. Despite the many tales of amorous governesses and wicked schoolgirls leading a young maiden down the road of vice, I discovered the pleasure to be had from it in the same way one would scratch an itch, or stretch their muscles on awakening, without the necessity of any training at all.

Yet it's a mystery to me how, in my child's mind, I came to understand without being told that I must hide this natural act beneath my bedcovers at night. Long before I understood what it was to be aroused by the sight of a well-proportioned man in the glorious state in which he was made, I was plagued by vague imaginings, and always looked forward to my nightly ritual. Once darkness had fallen over my bedroom, my hand snaked beneath the bedclothes, beginning slowly, rubbing and massaging myself into a state of blind oblivion, until my whole body stiffened, and after a wave of blissful contortion, I was released to a most languid state before drifting into sleep.

But it was the contents of those vague thoughts, as I grew, that most troubled me, for in my youth I suffered a deep and shameful love for my father, the god of my idolatry. In truth I saw little of him, and I suppose this helped to form my image of him, not as father, but as Master, of the plantation, its inhabitants and his lone daughter. The feeling was biblical in its intensity, like the salacious daughters of Lot, in the way of scriptural tales dear to the medieval mind, now so often given the boot of a Sunday.

I was raised by my beloved nurse, whom I called Nana. My mother was a flighty and selfish creature who lived for the most part in Paris, spending the money my father sweated in the fields beside his slaves to earn. She claimed a weak constitution that made the climate of Martinique dangerous to her, though I knew it was mere boredom, love of luxury and excitement that caused her to desert us, leaving my father to a bleak existence, with no legitimate freedom to find comfort elsewhere.

He had many friends amongst the planters who'd also lost their wives, generally to childbirth or one of the fevers that swept the islands, and though he did not approve, I suppose it was difficult not to forgive them for finding solace in the quarters, taking mistresses from among the most exotic and lovely of the Africans, as well as the mulattos and quadroons, the bastard daughters and granddaughters of those who'd done the same a generation before. On many of the plantations, the gentleman's native lady sat at his table, and his bastard children played side by side with his white ones, while the most promising were occasionally sent to France to be educated. It was a thing to which I grew accustomed, despite my father's disapproval, and I came to believe it the better way, especially as the republican fervor to emancipate the slaves swept the island.

Martinique in those days was a place for intrepid adventurers, suitable to our pirate founders, though Man's mischievous desire to incessantly categorize his own was fully in evidence. As with the blacks, divided into tiers of Free Blacks and mulattos and house slaves and field slaves, the whites, too, were of many classes, principally two; the lower, the

petits blancs

, including the

engagés

, bonded servants or those sentenced to the island for petty crimes, and the upper, the

grands blancs

, the wealthiest of the plantation owners, especially those of noble families. Of course, not all grew wealthy, and many a failed planter still proudly produced his certificate of nobility on any pretext to anyone who would look at it, an affectation my father despised.

For he was truly of the peerage, his father having been a marquis in the north of Gascony, though not particularly well-off. As his lands failed, my grandfather drifted north, drawn by the opportunities of the great seaport of La Rochelle. The French government, in an effort to settle the island, incessantly proclaimed Martinique a land of opportunity. As he watched the vast wealth flowing in and out of the port from the trade in sugar, he chose to risk all, to emigrate and start his own plantation.

The French Revolution came near the time of my grandfather's death, and it robbed my father legally of his title. Years later, when Napoleon restored the status of the

ancien regime

, it no longer mattered to him, and even less to me, for the nobility of his mien and appearance was not a thing that could be bestowed by a piece of parchment.

Yet despite his nobility, my father had blinded himself to slavery, to its essential evil. He was far better to his people than most, which in some ways made it worse, for he seemed to believe he could infuse something evil with goodness and fair play. He encouraged them to the Church, to marry and start families, and though this was unarguably to his advantage, since every new life carried the odious appendage of a value in coin, he genuinely believed it brought happiness and stability. His physician cared for our slaves, and he gave his people both Saturday and Sunday free, unless there was a harvest. In this way, they could work their own small plots beside their shacks, to vary their diet, and still have a day of Sabbath rest. He decreed other improvements to their lives, and fostered their gatherings, the singing and dancing and storytelling that offered some relief from the labor. The unremitting, ceaseless toil of the cane, sun-up to darkness, the sweat of the fields and the inferno of the mill.

However, he discouraged strong drink, particularly their favored brew. The natives called it

tafia

, the whites "black lightening," pure alcohol, a cast-off of rum that hadn't been aged. I'd never tasted it, but had smelled it, and that was enough. Trapped in its ruthless coils, death could come upon a man long before his time. Of course, my father was often defied in these edicts, and punishment was doled out for offenses; the cane, the shackles, even the whip, though he held a temperate hand, and the song of the lash was rarely heard at Presque Isle.

But Martinique was a place of violent contrasts, in the island and people. It was often said to be two islands unnaturally joined, the south with its white sand and bright blue water, and the mountainous jungle of the north, where the cane grew. Even the winds were contrary that blew over Presque Isle, our small manor house, winds that could bring a hurricane in their wake, when the two opposing forces slammed against one another, joining in a tumultuous embrace that uprooted trees and tore homes apart.

And so it shouldn't have been surprising, I suppose, that despite his temperance, my father on occasion slipped from his pedestal, driven near to madness by his loneliness. It was a thing for which I did not despise him, especially considering the openly animalistic behavior of many of the young sons of the planters, who literally ran wild in the quarters, until the mulattos of the island began to outnumber the whites, a matter of grave concern to him. My father berated these jaded young libertines for their devotion to wine and native flesh. He walked alone.

And how I despised my mother for this! For her desertion, not of me, but of him. When she wrote on occasion suggesting I join her in Paris, my reaction was so distressing my father never put me from him, a thing I believe caused her little grief. And as I grew older, I began to feel that I was the rightful one to have her place, for I worshipped that which she had scorned. My father was still a man in his prime, with broad shoulders and a masculine countenance graced with piercing hazel eyes, a face I never tired of contemplating. By the age of fourteen I sat as hostess, and took care to ensure what little comfort could be given him came from my hand, preparing his favorite foods, washing and pressing his clothes to perfection rather than allowing servants or slaves to do it, reading aloud to him in the evening. Though I sported with friends, ran free on the sand and rode bareback in the sun, these joys still paled in comparison to anything large or small I could do for him.