Marmee & Louisa (48 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

Sybil finds a note her mother wrote to her but failed to deliver. “I implore you to leave this house before it is too late. Run away. Be free.” Finally able to escape from her uncle, Sybil is “saved” by Guy, whom she marries. But this hasty resolution does not leave her happy. She is haunted by the memory of her mother, as Louisa was. “Over all these years, serenely prosperous, still hangs for me the shadow of the past, still rises that dead image of my mother.”

Exhausted by her visit with her father, Louisa returned to her bed at the Highlands. She had lost more than thirty pounds since the fall. She was not at her father’s side when he died, on Sunday, March 4, at the house on Louisburg Square, and may not have even known he died. It seemed to Anna, though, that “with his departure her last earthly care left her, & she felt free to follow, & be at rest.”

Anna was called to the Highlands that day. Louisa “had taken ill the afternoon before,” complaining of a pain like a huge weight on her head, which suggests she had a stroke, or cerebral hemorrhage. She grew “rapidly worse, and lay unconscious” by the time Anna arrived. “She never knew me, but drifted quietly away as she had always prayed she might. Painless, & unaware of her condition, and our grief, she lay till early Tuesday morning,” March 6, 1888, “when just at dawn without a sigh she passed away.” Fifty-five years old, Louisa had been in poor health nearly half her life.

1320

“The loss of this talented writer will be felt far and wide among the many readers of her favorite books,” the

New York Times

announced the next morning in a page-one obituary. The packaging of Louisa as a little woman—schoolteacher, nurse, and writer, devoted to the care of her parents—began immediately, along with the idea that her mother was irrelevant. “She was educated as a school teacher under the tutelage of her father and Henry D. Thoreau,” the

Times

continued. “Mr. Alcott was stricken with paralysis in 1882, and since that time and up to that of her own fatal illness, she was his constant and loving nurse.”

Anna, at fifty-seven “the only standby of this large family,” in her words, was the last surviving Alcott. Like Abigail and Louisa, she found it “hard to be happy without mother or sisters.”

1321

Fred and John Pratt were in their twenties; Fred was already married, and both young men were employed by their aunt’s publisher Roberts Brothers. Eight-year-old Lulu soon returned to Zurich, at her father’s request, to his custody. Anna and John spent nearly a year with Lulu in Switzerland, helping her adjust. Lulu later married, had a daughter, and died in Switzerland in 1975. Anna survived Louisa by only five years.

None of Louisa’s survivors had to worry about money. At her death she was the country’s most popular author, and had earned more from writing than any male author of her time. In the decade after

Little Women

was published, according to the

Boston Herald

, she sold more than half a million books in America alone.

1322

Ten years later, when Roberts Brothers was sold, it had printed nearly two million copies of her books. By the mid-twentieth century more than two million copies of

Little Women

alone were in print, and the most circulated books at the New York City Public Library were

Little Women

and Anne Frank’s diary. Louisa’s novel has been translated into scores of languages, including Flemish, Arabic, Portuguese, Urdu, Persian, and Japanese.

In Boston a few months after Louisa’s death, the New England Woman Suffrage Association held a ceremony in honor of her eighty-eight-year-old cousin Samuel E. Sewall. The ancient lawyer and abolitionist, who had been born only a year before his first cousin Abigail May, rose from his chair to address the crowd. “Old Cato, whenever he was finishing a speech in the Senate, always added: ‘This I say, and Carthage must be destroyed!’ So I conclude, ‘The emancipation of women must be carried!’”

1324

Conclusion

F

reedom was always my longing, but I have never had it,” Louisa wrote near the end of her life. She accepted her place beside Abigail among that “Sad sisterhood of disappointed women,” but never ceased hoping for the day when men and women could live equally and with mutual respect. Louisa dreamed of a world in which women would have the same public rights as men—to vote, travel, speak out, and run governments.

In the end, Louisa May Alcott was her mother’s daughter. As willful, valiant, and loving as Abigail, she lived out her mother’s hopes and fulfilled many of her mother’s dreams. Neither woman achieved all she desired, but together they paved the way for modern women. Both wanted equal rights, but neither could find a way to live as men’s equal. Each chose at age thirty to avoid a traditional female role. Abigail married a reformer who seemed to share her belief in gender equality; Louisa decided to have a career and go off to war. This decision to become a “self-made woman” had disastrous consequences for both women. Failing to create an egalitarian or satisfying marriage, Abigail leaned on her daughters for emotional and financial support. Louisa’s decision to behave like a man in the world left her, ironically, lonely and dependent on her mother.

Unable to find a partner who was her equal, Louisa found comfort in Abigail who, more than anyone else, understood and sympathized with her. With her vivid imagination, however, Louisa would doubtless have preferred the kind of love that Margaret Fuller found in Italy. In a better

world, Louisa believed, women would have the opportunity to work and be heard in the world, to “try all kinds” of lovers, to raise families, and to share the burdens and pleasures of domestic life. In short, they would be equal to men.

“There are plenty [of people] to love you,” Marmee tells Jo in

Little Women

, “so try to be satisfied with father and mother, sisters and brother, friends and babies, till the best lover of all comes to give you your reward.”

Louisa’s alter ego replies, “Mothers are the

best

lovers in the world; but I don’t mind whispering to Marmee, that I’d like to try all kinds. It’s very curious, but the more I try to satisfy myself with all sorts of natural affections, the more I seem to want.”

In Louisa’s essay

Shawl-Straps

, written a few years before her mother died, she advised young women to explore the world, as Dr. Johnson in the eighteenth century had advised young men. Abigail had also told her daughters: learn your own country and culture, and educate yourself further through travel.

To Louisa, her lengthy tour of Europe with her sister May and Alice Bartlett had “proved,” despite “prophecies to the contrary,” that “three women, utterly unlike in every respect, [could travel] unprotected safely over land and sea . . . experience two revolutions, an earthquake, an eclipse, and a flood,” and “yet [meet] with no loss, no mishap, no quarrel, and no disappointment . . .

We would respectfully advise all timid sisters now lingering doubtfully on shore, to strap up their bundles in light marching order, and push boldly off. They will need no protector but their own courage, no guide but their own good sense and Yankee wit, and no interpreter if that woman’s best gift, the tongue, has a little French polish on it. Wait for no man, but take your little store and invest it in something far better than Paris finery, Geneva jewelry, or Roman relics.

Bring home empty trunks, if you will, but heads full of new and larger ideas, hearts richer in the sympathy that makes the whole world kin, hands readier to help on the great work God gives humanity, and souls elevated by the wonders of art and diviner miracles of nature. Leave . . . discontent, frivolity and feebleness among the ruins of the old world, and bring home to

the new the grace, the culture, and the health which will make American women what they just fail over being, the bravest, brightest, happiest, and handsomest women in the world!

Stand up among your fellow men

, Joseph May had said to his son on the completion of his man’s education. Improve your advantages. Go anywhere.

A woman can accomplish as much as a man

, Abigail had told her daughters so often they came to believe her. Educate yourself up to your senses. Be something in yourself. Let the world know you are alive. Push boldly off. Wait for no man. Have heads full of new and larger ideas. And proceed to the great work God gives humanity.

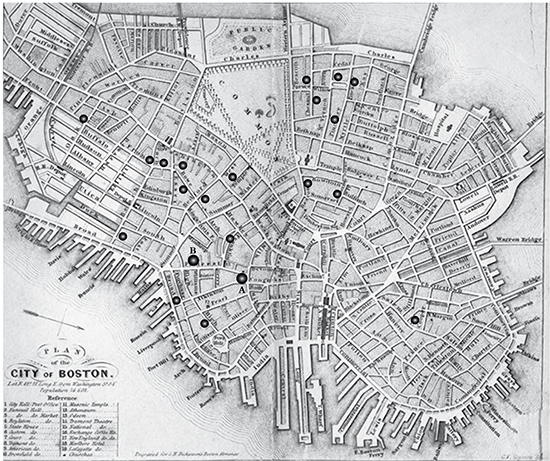

Map of Boston in 1840, when seven-year-old Louisa and family departed after a stay of five years. The 21 dots on the map indicate locations where the Alcotts lived in Boston. At least four additional locations are off the map to the west: Dunreath Ave. at Warren St. in Roxbury, the nursing home in which Louisa died; and 81 West Cedar St., 29 Dedham St., and 26 E. Brookline St. in Franklin Square, all in the South End. The larger dot A marks Abigail’s birthplace, and B marks her childhood home on Federal Court.

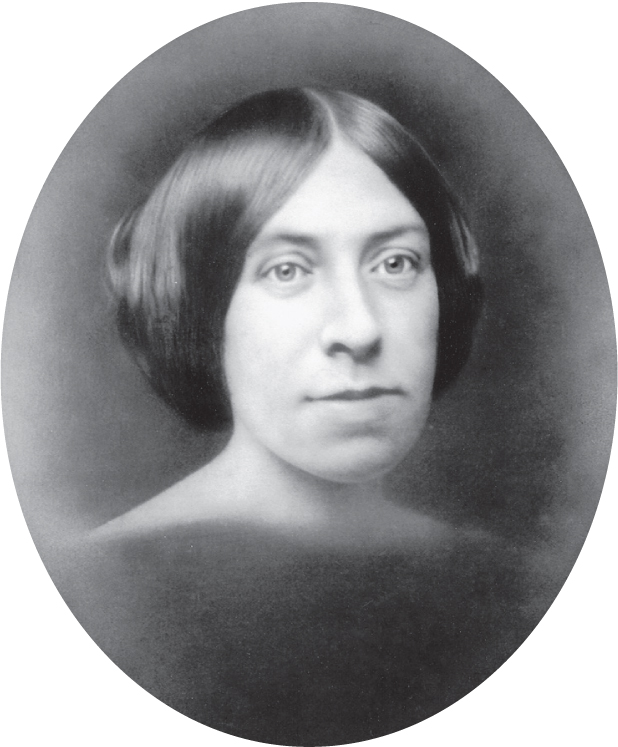

Abigail May Alcott in her sixties. No earlier image of Abigail survives.

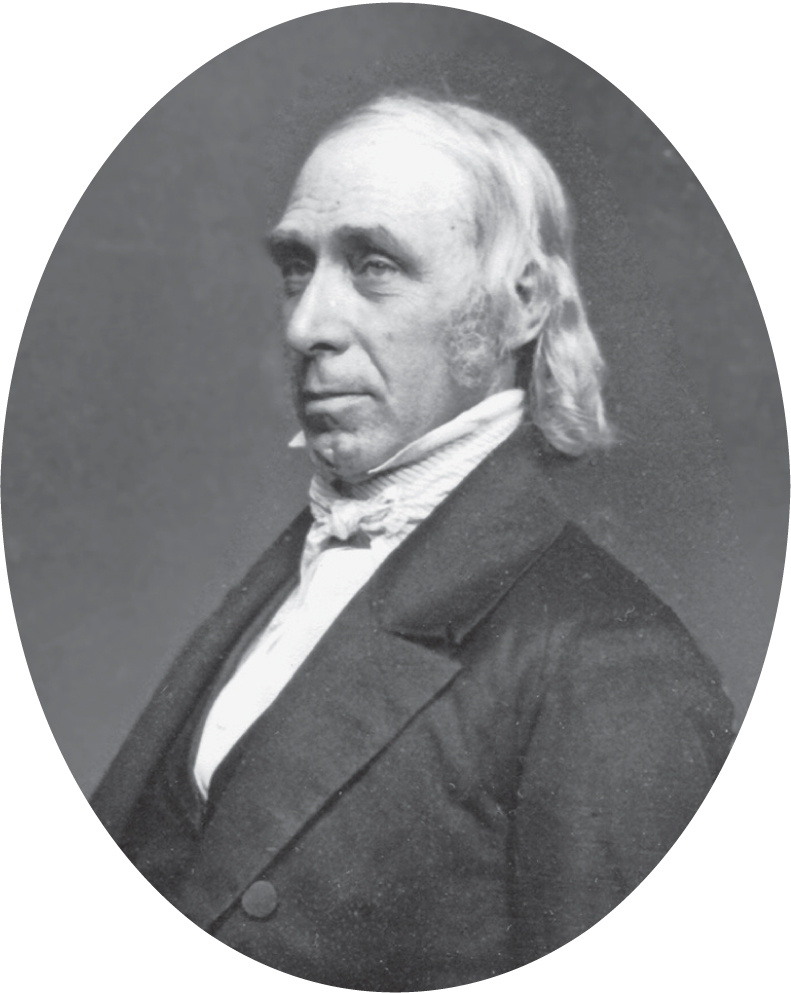

Bronson Alcott in his sixties.

Louisa May Alcott as a young woman.

Anna Alcott, Louisa’s older sister, as a young adult.