Mark Griffin (18 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Minnelli’s screen credit for MGM’s “super spectacular”

Ziegfeld Follies

. Many promising sequences were cut from the film: Fred Astaire’s “If Swing Goes, I Go, Too,” Avon Long serenading Lena Horne with “Liza,” and Fanny Brice whooping it up as the incorrigible Baby Snooks. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Ziegfeld Follies

. Many promising sequences were cut from the film: Fred Astaire’s “If Swing Goes, I Go, Too,” Avon Long serenading Lena Horne with “Liza,” and Fanny Brice whooping it up as the incorrigible Baby Snooks. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Billed as “the screen’s biggest picture,”

Ziegfeld Follies

was such a massive undertaking that it proved to be too much for George Sidney, who vacated the director’s chair after helming several sequences.

aa

By May 1944, Minnelli had officially succeeded Sidney as director, though the movie was so big that directorial chores were ultimately divvied up among Robert Lewis, Lemuel Ayres, Roy Del Ruth, Norman Taurog, and Merril Pye. As a result, there would be a noticeable variance in the quality of the sketches. Some routines dazzled, others fizzled. To Minnelli fell the plum-star turns, including several elaborate production numbers featuring the most graceful star in Metro’s firmament: the inimitable Fred Astaire.

Ziegfeld Follies

was such a massive undertaking that it proved to be too much for George Sidney, who vacated the director’s chair after helming several sequences.

aa

By May 1944, Minnelli had officially succeeded Sidney as director, though the movie was so big that directorial chores were ultimately divvied up among Robert Lewis, Lemuel Ayres, Roy Del Ruth, Norman Taurog, and Merril Pye. As a result, there would be a noticeable variance in the quality of the sketches. Some routines dazzled, others fizzled. To Minnelli fell the plum-star turns, including several elaborate production numbers featuring the most graceful star in Metro’s firmament: the inimitable Fred Astaire.

A pair of Astaire showcases in which the forty-five-year-old hoofer was effectively teamed with twenty-two-year-old Lucille Bremer (fresh from

Meet Me in St. Louis

) immediately captured Vincente’s imagination. Dipping into his file of illustrated clippings for inspiration, he would lavish these sequences with the same inventiveness and visual ingenuity that had distinguished his work on the Broadway stage.

Meet Me in St. Louis

) immediately captured Vincente’s imagination. Dipping into his file of illustrated clippings for inspiration, he would lavish these sequences with the same inventiveness and visual ingenuity that had distinguished his work on the Broadway stage.

“This Heart of Mine: A Dance Story” was fashioned around a song featuring a lilting melody by Harry Warren and overripe lyrics by none other than Arthur Freed (“And then quite suddenly I saw you and I dreamed of gay amours. At dawn I’ll wake up singing sentimental overtures.”). The scenario was pure fairy tale: On a summer evening in 1850, a ball is in progress inside a glittering pavilion that resembles a gigantic wedding cake. The guests include Astaire, sporting a monocle and an expression of ne’er-do-well, and a tiara-topped Bremer, looking très distingué in a luxurious chinchilla wrap. In this gloriously artificial setting, Astaire’s suave imposter pilfers Bremer’s diamonds, though she doesn’t seem to mind, as he’s also stolen her heart. The “story” may have been slight, but who cared? As glamorous spectacle, the sequence achieves some kind of Freed Unit nirvana.

If all that weren’t enough, “This Heart of Mine” also marked the first teaming of Minnelli and designer Tony Duquette, who created some of the exquisitely over-the-top trappings for the sequence. “Vincente and Tony were very close,” says designer and one-time Duquette assistant Leonard Stanley:

The first movie Tony worked on with Minnelli was

Ziegfeld Follies

, which was done in 1944 but never released to the public until 1946. It was really made during the war when Tony was in the army and stationed at Long Beach or somewhere near the coast. He would occasionally go off by himself because he was doing these sketches for Vincente for

Ziegfeld Follies

. . . . One day, these two MPs saw him sketching. They actually thought he was a spy sketching the military layout of the camp that Tony was stationed at. But it was really all of these designs for Vincente’s movie. Tony—

a spy

! That just broke me up.

1

Ziegfeld Follies

, which was done in 1944 but never released to the public until 1946. It was really made during the war when Tony was in the army and stationed at Long Beach or somewhere near the coast. He would occasionally go off by himself because he was doing these sketches for Vincente for

Ziegfeld Follies

. . . . One day, these two MPs saw him sketching. They actually thought he was a spy sketching the military layout of the camp that Tony was stationed at. But it was really all of these designs for Vincente’s movie. Tony—

a spy

! That just broke me up.

1

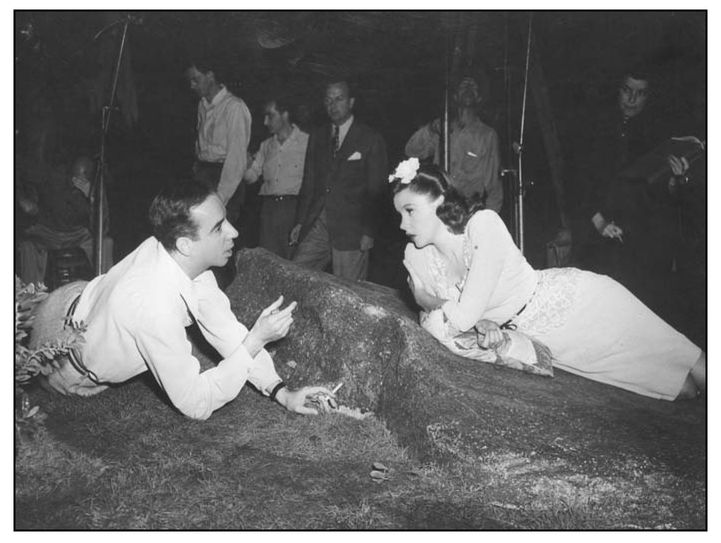

Astaire and Bremer’s second teaming, “Limehouse Blues,” was inspired by the haunting Gertrude Lawrence tune of the same name and Lillian Gish’s silent classic

Broken Blossoms

. The critics were all in accord that this sublime “dramatic pantomime” was the highlight of Freed’s

Follies

. Appearing in Oriental make-up, Astaire is Tai Long (“in his shifty slouch, one detects the characteristic movement of the outcast”). Tai inhabits a seedy waterfront world of streetwalkers, sailors, and drunken vagrants. Minnelli had a field day filling up his frame with all of the necessary types from Central Casting: a wizened Chinaman smoking an opium pipe, some overeager trollops, a band of raucous buskers, and a transient pushing a Victrola in a baby carriage.

Broken Blossoms

. The critics were all in accord that this sublime “dramatic pantomime” was the highlight of Freed’s

Follies

. Appearing in Oriental make-up, Astaire is Tai Long (“in his shifty slouch, one detects the characteristic movement of the outcast”). Tai inhabits a seedy waterfront world of streetwalkers, sailors, and drunken vagrants. Minnelli had a field day filling up his frame with all of the necessary types from Central Casting: a wizened Chinaman smoking an opium pipe, some overeager trollops, a band of raucous buskers, and a transient pushing a Victrola in a baby carriage.

Out of the London fog appears Bremer’s Moy Ling (“to look into her eyes is to look into the solemn depths of a cathedral”). Clad in retina-arresting canary yellow, Moy is the only spot of brightness in Tai’s colorless existence. He is immediately entranced and begins following her. After observing Moy

as she admires an Oriental fan in a shop window, Tai is mistaken for a robber and shot. On the brink of death, he falls into a hallucinatory delirium—though even in his fantasy, Tai’s search for the elusive Moy continues. Now in possession of the fan she once coveted, Moy uses it to lure Tai into the darkened depths of his subconscious. When he finally reaches Moy and touches the fan, all is suddenly light—and chinoiserie. They dance together and achieve the sort of harmonious union that wasn’t possible back in the real world. “Limehouse Blues” would be hailed as “the finest production number ever poured into a screen revue,” and Minnelli considered the end result “a total triumph.”

2

The sequence is not only a visual stunner but also achieves something distinctly Minnelli: taking the viewer inside an unreality (Astaire’s dream) within a “reality” (MGM’s version of old Chinatown) that was itself a nonreality to begin with.

as she admires an Oriental fan in a shop window, Tai is mistaken for a robber and shot. On the brink of death, he falls into a hallucinatory delirium—though even in his fantasy, Tai’s search for the elusive Moy continues. Now in possession of the fan she once coveted, Moy uses it to lure Tai into the darkened depths of his subconscious. When he finally reaches Moy and touches the fan, all is suddenly light—and chinoiserie. They dance together and achieve the sort of harmonious union that wasn’t possible back in the real world. “Limehouse Blues” would be hailed as “the finest production number ever poured into a screen revue,” and Minnelli considered the end result “a total triumph.”

2

The sequence is not only a visual stunner but also achieves something distinctly Minnelli: taking the viewer inside an unreality (Astaire’s dream) within a “reality” (MGM’s version of old Chinatown) that was itself a nonreality to begin with.

“One of the things that I always remember about the mise-en-scène of ‘Limehouse Blues’ is that it’s really disorienting in terms of ‘film space,’” says Freed Unit scholar Matthew Tinkcom:

You’re moving through all of these different kinds of dream-like layers and smoke and camera movement. As you’re watching, there comes a moment when you say to yourself, “I’m not in any kind of space of realism . . .” because in that sequence, we’re moving through psychological space. We’re into a landscape of the mind and fantasy and desire. What’s amazing about it is that it’s very atypical of Hollywood continuity. The thought about continuity was always “Do not disorient the spectator . . .” but here it’s done in a really powerful way. It’s about the Astaire character’s shock and grief over the loss of his own fantasy and being forced to leave the realm of the fantastic. . . . It’s really the same thing with Minnelli, who always wants to get back into the mental landscape because that’s so much richer and more interesting.

3

3

Although Norman Taurog or Robert Z. Leonard could have directed these

Follies

episodes in a more than capable manner, Minnelli managed to invest even the most stylistically fixated material with an unusual power and an undercurrent of emotionality that other directors on the studio payroll wouldn’t have considered. In other hands, Astaire and Bremer’s unrequited romance in old Chinatown would have been tossed off as cutesy pastiche, whereas Vincente takes his fantasy very seriously. Or as William Fadiman once observed, Minnelli “was a man who could honestly believe in make-believe.”

4

Follies

episodes in a more than capable manner, Minnelli managed to invest even the most stylistically fixated material with an unusual power and an undercurrent of emotionality that other directors on the studio payroll wouldn’t have considered. In other hands, Astaire and Bremer’s unrequited romance in old Chinatown would have been tossed off as cutesy pastiche, whereas Vincente takes his fantasy very seriously. Or as William Fadiman once observed, Minnelli “was a man who could honestly believe in make-believe.”

4

“Limehouse Blues” introduced a theme that would resurface time and again in Minnelli’s movies. A protagonist in search of romance, a more

adventurous way of life, or an authentic self must go within in order to find it. While the outside world will inevitably disappoint, the inner world will uplift, heal, and complete.

adventurous way of life, or an authentic self must go within in order to find it. While the outside world will inevitably disappoint, the inner world will uplift, heal, and complete.

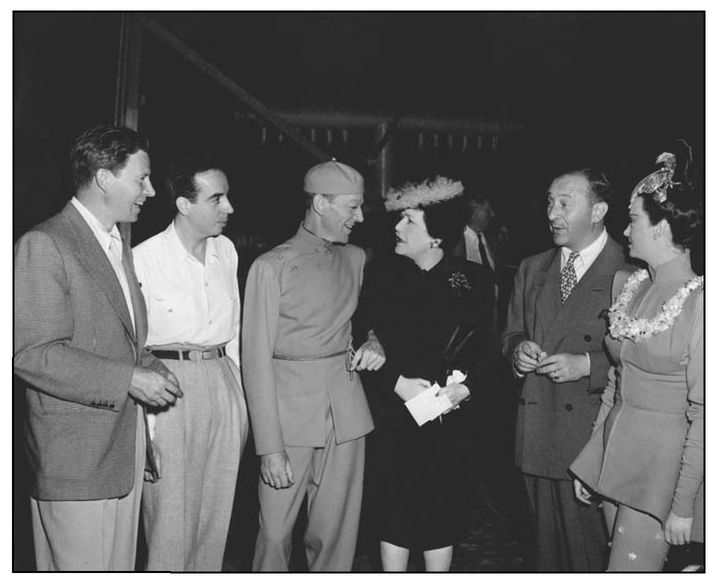

George Murphy, Minnelli, Fred Astaire, Arthur Freed, and Lucille Bremer welcome gossip columnist Louella Parsons to the set of

Ziegfeld Follies

. Astaire and Bremer are in costume for the extraordinary “Limehouse Blues” sequence. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Ziegfeld Follies

. Astaire and Bremer are in costume for the extraordinary “Limehouse Blues” sequence. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Fred Astaire had performed “The Babbit and the Bromide” on Broadway, but for the version of the number included in

Ziegfeld Follies

, he was paired with Metro’s other dancing virtuoso, Gene Kelly. “They were completely different,” Minnelli would say of his two stars. “Fred Astaire is very elegant, high up in the air. . . . Gene is very athletic and down-to-earth. . . . In

Ziegfeld Follies

, when they worked together, we thought they’d never finish, because they would upstage each other. One would say, ‘Well, now, suppose we try this step. . . .’ They Alphonse’d and Gaston’ed each step because they had so much respect for each other.”

5

“The Babbit and the Bromide” serves as something of an extended “Coming Attraction,” as later in his career, Vincente would bounce back and forth between Astaire and Kelly vehicles.

Ziegfeld Follies

, he was paired with Metro’s other dancing virtuoso, Gene Kelly. “They were completely different,” Minnelli would say of his two stars. “Fred Astaire is very elegant, high up in the air. . . . Gene is very athletic and down-to-earth. . . . In

Ziegfeld Follies

, when they worked together, we thought they’d never finish, because they would upstage each other. One would say, ‘Well, now, suppose we try this step. . . .’ They Alphonse’d and Gaston’ed each step because they had so much respect for each other.”

5

“The Babbit and the Bromide” serves as something of an extended “Coming Attraction,” as later in his career, Vincente would bounce back and forth between Astaire and Kelly vehicles.

At one point, Judy Garland had been scheduled for “The Babbit and the Bromide,” along with virtually every other

Follies

sequence. “I Love You More in Technicolor Than I Did in Black and White” was to have reunited Garland with her frequent costar Mickey Rooney. When Rooney was drafted into the army, the sketch was shelved, and his reteaming with Garland would have to wait until 1948’s

Words and Music

. Judy ultimately ended up in a dynamite

Follies

sequence—one that had been cast aside by another star. The Freed Unit’s wunderkinds, Kay Thompson and Roger Edens, had conceived “The Great Lady Has an Interview” as a sort of self-parody for Greer Garson. The devastatingly witty number would offer Metro’s Oscar-winning grand dame an opportunity to let her hair down and spoof her own noble image.

Follies

sequence. “I Love You More in Technicolor Than I Did in Black and White” was to have reunited Garland with her frequent costar Mickey Rooney. When Rooney was drafted into the army, the sketch was shelved, and his reteaming with Garland would have to wait until 1948’s

Words and Music

. Judy ultimately ended up in a dynamite

Follies

sequence—one that had been cast aside by another star. The Freed Unit’s wunderkinds, Kay Thompson and Roger Edens, had conceived “The Great Lady Has an Interview” as a sort of self-parody for Greer Garson. The devastatingly witty number would offer Metro’s Oscar-winning grand dame an opportunity to let her hair down and spoof her own noble image.

The irresistible sketch concerns a self-adoring star who comes complete with a butler named Fribbins and a prominently displayed portrait depicting her humble, barefoot beginnings. During a staged press conference, “the glamorous, amorous lady” sings the praises of her forthcoming biopic, “Madame Crematante”—a paean to the inventor of the safety pin.

Upon hearing the piece, which one critic would later pronounce “as wholesome as a slug of absinthe,” Garson demurred. It was just as well, as by now the musical content of the sketch required the services of a legitimate showstopper. Enter Judy Garland. As Arthur Freed noted, “Judy loved doing sophisticated parts like ‘The Interview’ sequence . . . but mind you, that particular number was not one of her biggest successes, except with a certain group.” Of course, the group that Freed was referring to was the most fanatical and fiercely devoted component of Judy’s fan base—the gay men who were instrumental in forming the Garland cult. As biographer Christopher Finch observed, “Hard core Garland aficionados swooned over Madame Crematon [

sic

]. This was the Judy they had hoped for, the Judy of their most cherished dreams—a camp Madonna.”

6

sic

]. This was the Judy they had hoped for, the Judy of their most cherished dreams—a camp Madonna.”

6

Film historian David Ehrenstein recalled attending a screening of

Ziegfeld Follies

at a Greenwich Village retro house, and as the title card announcing Garland’s sequence appeared, the audience became especially attentive. “I remember there were these two guys sitting next to me and one of them said to the other, ‘Okay, here comes “The National Anthem.”’ It’s hilarious and it’s deeply hip at the same time. . . . There’s this wonderful combination of intense sophistication and naiveté of material in the Freed Unit musicals.”

7

And more than a touch of lavender. The handsome newsboys who receive Our Lady of Culver City on bended knee and dance into the star’s sanctuary, linked arm in arm, could be charter members of Garland’s own fan club.

Ziegfeld Follies

at a Greenwich Village retro house, and as the title card announcing Garland’s sequence appeared, the audience became especially attentive. “I remember there were these two guys sitting next to me and one of them said to the other, ‘Okay, here comes “The National Anthem.”’ It’s hilarious and it’s deeply hip at the same time. . . . There’s this wonderful combination of intense sophistication and naiveté of material in the Freed Unit musicals.”

7

And more than a touch of lavender. The handsome newsboys who receive Our Lady of Culver City on bended knee and dance into the star’s sanctuary, linked arm in arm, could be charter members of Garland’s own fan club.

Dancer Bert May, who plays one of the reporters in Garland’s sketch, made one of his first film appearances in

Ziegfeld Follies

: “I was only a teenager

and here I am in a movie with Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, and Judy—I like to say I started at the top and worked my way down.”

ab

May remembered that it was actually Chuck Walters who staged and choreographed Garland’s “Interview.” Though Walters had carefully planned the sequence, Freed decided that Minnelli should shoot it. “Every bit of action in that number was mine. I almost cried,” Walters revealed.

8

It wouldn’t be the last time that Minnelli and Walters would “collaborate” on a picture.

Ziegfeld Follies

: “I was only a teenager

and here I am in a movie with Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, and Judy—I like to say I started at the top and worked my way down.”

ab

May remembered that it was actually Chuck Walters who staged and choreographed Garland’s “Interview.” Though Walters had carefully planned the sequence, Freed decided that Minnelli should shoot it. “Every bit of action in that number was mine. I almost cried,” Walters revealed.

8

It wouldn’t be the last time that Minnelli and Walters would “collaborate” on a picture.

Vincente and Judy were reunited for “The Interview”—but only while the cameras were rolling. After

Meet Me in St. Louis

, there had been a romantic detour. “Judy had left me,” Minnelli remembered. “She’d been seeing another man before we started going together. He was tortured and complicated and very much the intellectual. She simply gravitated back to him.” Of course, the deep-thinker in question was Joe Mankiewicz. Minnelli may have worshipped Garland’s star quality, but Mankiewicz was able to completely relate to Judy as a woman: “I remember her as I would an emotion, a mood, an emotional experience that is an event.”

9

Meet Me in St. Louis

, there had been a romantic detour. “Judy had left me,” Minnelli remembered. “She’d been seeing another man before we started going together. He was tortured and complicated and very much the intellectual. She simply gravitated back to him.” Of course, the deep-thinker in question was Joe Mankiewicz. Minnelli may have worshipped Garland’s star quality, but Mankiewicz was able to completely relate to Judy as a woman: “I remember her as I would an emotion, a mood, an emotional experience that is an event.”

9

Other books

Beware The Beasts by Vic Ghidalia and Roger Elwood (editors)

Dawn Autumn by Interstellar Lover

A Touch of Confidence by Jess Dee

Out of This World by Graham Swift

Holding On by Rachael Brownell

The Mysterious Death of Mr. Darcy by Regina Jeffers

Daughters Of Eden: The Eden Series Book 1 by Bingham, Charlotte

Chains Around the Grass by Naomi Ragen

Never Fuck Up: A Novel by Jens Lapidus

Hat Trick by Alex Morgan