Maritime Murder (18 page)

Authors: Steve Vernon

Tags: #History, #General, #Canada, #True Crime, #Murder

In

1898

he met fifty-six-year-old Camille Cecile Holland in a time of mutual distress. He was still in mourning for his lost military pension and she was still in love with her childhood sweetheart, a young naval officer who had drowned in the performance of his duty. She still wore his ring decades later, and until she met Dougal, she had given no thought to the possibility of there ever being any other love but her childhood sweetheart. Dougal swept down on her like a hawk upon a field mouse, his eyes squarely fixed upon the seven-thousand-pound inheritance that Camille had recently received. In her state of over-advanced bereavement, she made herself an easy victim for Dougal's slick approach.

“He was a tall military looking man,” she wrote in her diary, “who referred to himself as Captain Dougal. He had a fine pointed beard, a stalwart chest, plentiful hair, and a clever touch with a pen.”

Camille fell in love with “Captain” Dougal, and rented a small, modest home for the two of them to reside in for thirty shillings a week. Dougal had other plans, however. He got in touch with a land agent in January

1899

and arranged a contract in his own name using Camille's inheritance fund to purchase a small but costly

country estate known as Moat Farm. The farm was at the end of a muddy cart track, and the house was only accessible by a footbridge over a naturally occurring moat. It was, in fact, the perfect trap.

When Camille found out about the farm, she took action, getting in touch with the land agent, destroying Dougal's unfinanced contract, and securing a contract of her own that would name her as the sole owner of Moat Farm. This act of independence must have tested Dougal's patience to the limit, but he could not do anything against her wishes because, in point of fact, Camille had not yet married him.

It was at this point that Dougal's third wifeâSarah Henrietta Whiteâstepped back into his life. She had heard of his good fortune and most definitely wanted a part of it. Amazingly enough, Camille apparently allowed Dougal's wife to move in with them at the farm. Sarah White immediately took up residence, and was often seen about the grounds wearing what looked to be Camille's best gowns.

Shortly after White arrived in the early spring of

1899,

Dougal began circulating the story that Camille had gone abroad and was travelling on the continent. This story was believed for several

years, while Dougal lived it up at the farm with his third wife, Sarah,

and a series of working girls who were hired and fired just as quickly as Dougal tired of them.

Eventually, in

1902

, White tired of Dougal's brutality and womanizing ways. Dougal seemed unbothered by his third wife's departure. The stream of female servants and working girls increased. It was March

1903

before the truth finally came out, when Dougal slipped up and was caught forging Camille's signature on a cheque.

After four years of living the life of Riley, “Bluebeard” had finally been found out. No one would now believe his story regarding Camille's absence.

A search party took action. It took four weeks of searching, but a woman's body was found buried in a ditch. The corpse was rotted beyond identification, but there was enough left of her footwear for Camille's shoemaker to identify the boots as belonging to her.

“If Dougal had thought to bury his victim in the farmyard waste heap,” the pathologist later remarked, “the acidic nature of the ordure would have left little or nothing to identify.”

It was obvious that Dougal had shot her in cold blood. Although he argued fervently that it had been nothing more than an unplanned accident, and the by-product of one bad argument and two too many brandies, the jury took less than a single hour to find Quartermaster Sergeant Samuel Herbert Dougal guilty of premeditated murder. Dougal was sentenced to be hanged on June

22

,

1903

, at Chelmsford Prison.

“Are you guilty or not guilty?” the prison chaplain asked as the executioner wrapped his hand around the gallows lever. Dougal would not answer.

“Are you guilty or not guilty?” the prison chaplain repeated.

“Guilâ ,” was Dougal's last syllable as he dropped through the trapdoor into eternity. As for his two Halifax wivesâLovenia Martha and Mary Herbertaâtheir bodies still lie undisturbed in the quiet Fort Massey Cemetery.

Neil McFadyen

Pictou County, Nova Scotia

1848

N

eil McFadyen was born and raised on the Isle of Tiree, a small Scottish island situated just off of the coast of Argyll County. In 1824 he married a woman from the McKinnon family whose first name has unfortunately been lost in the annals of recorded history. It was a hard life and Neil was quite unhappy. A possible solution to his discontent came in 1827, when his father and his family booked passage to Cape Breton and invited Neil and his wife to accompany them. They moved to Moose River, a small settlement about forty kilometres southeast of Pictou, Nova Scotia.

There, Neil McFadyen built a small log cabin with his wife. The two of them raised several children. He picked up odd jobs wherever he could manage. Unfortunately, along with the odd jobs, he picked up more than he ought to have. Following a string of minor thefts, McFadyen found it necessary to travel in search of healthier working and living arrangements.

McFadyen left Pictou and found work in a New Brunswick lumber camp just off the Bay of Chaleur. It was here that he met Jamie Kier, a young man with a dream of building a new life for himself.

“I'd love to settle down and build myself a farm,” Jamie told McFadyen. “This lumbering is too much work with too little reward.”

“There's an awful lot of work in farming,” Neil McFadyen replied. “Have you given that much thought?”

“It's not the work I mind. It's the lack of permanence. I'd really love a chance to set down roots and just grow in the dirt. Right here, about the only roots I run into are the ones I cut down.”

“So what would you grow?” McFadyen asked.

“Oh, most anything, I suppose,” Jamie replied. “Beans and potatoes and beets and carrots and peasâjust for starters.”

“And do you have the money for it?” McFadyen asked.

“I have most of my money saved,” Jamie said, patting a buttoned pocket on his vest that jingled when he touched it. “My dad sent me some as well.”

“And does your dad live nearby?” McFadyen asked, trying to guess just how much money was crammed into that tightly buttoned vest pocket.

“My dad lives in New Brunswick,” Jamie replied. “He wants me to buy the farm next to his and settle down.”

“You know what I think?” McFadyen asked. “I think you ought to think about following me home to Pictou County.”

“Is that where you live?” Jamie asked.

“Sure,” McFadyen answered. “I live in Moose River, just a few miles from the Garden of Eden itself.”

Although Neil McFadyen was presenting his story in a slightly misleading fashion, he was actually telling the truth to the boy. The town of Moose River was just a few kilometres away from the small Nova Scotia community that had laid claim to the name “Garden of Eden,” for its location just to the north of Eden Lake.

“The Garden of Eden?” Jamie asked in disbelief.

“Sure, and I wouldn't be lying to you. You can grow nearly anything you want toâexcept maybe tiredâin the dirt over that way, and they're practically giving it away. Why don't you come home with me and I'll see you set up good and proper with a farm of your own. I might even find you a woman, so you could raise yourself a crop of children to work that farm for you.”

McFadyen laid it on just as thick as he was able.

“Can't you just picture yourself living the life of a proper country gentleman,” McFadyen went on, “with a pack of strapping young sons doing all your work, and a wife to bake you biscuits and serve you liquor and cream until your belly is so swollen you'll need an extra set of arms to tie your bootlaces with?”

Jamie listened intently.

“Just think about it,” McFadyen continued. “It's Nova Scotia. That's another term for âNew Scotland.' What better place for a stout Scot such as yourself to build himself a home? Come next year, you'll no doubt have raised enough money to buy your father a home where he can grow old in peace.”

“I like the sound of that last bit,” Jamie said.

Quicker than you could say, “Take care, young gentleman,” Neil McFadyen had talked young Jamie Kier into quitting his job as a lumberjack and catching the first ship bound for Pictou, making sure that Kier paid their fare along the way.

Throughout the short journey, McFadyen kept Jamie Kier's imagination ablaze with his tales of fertile wilderness. Night and day, he heaped lies and exaggerations upon the boy's hopes and dreams like they were nothing more than armloads of sun-seasoned kindling.

When they reached Nova Scotia, McFadyen and Kier spent the night sleeping rough in a ditch. It was the first day of July, and the weather was warm enough to allow the men to sleep rough as they did.

“Come tomorrow,” McFadyen promised, “you and I will walk to your new farm. I know of one such farm nearby that you can buy for a song, and the song needn't even be sung on key.”

In the morning they set off again. “It's just through these woods,” McFadyen directed.

They came to a small stream. “There's a dead log we can cross on,” McFadyen said. “You get to the other side, and we'll find dirt for the planting.”

Jamie stepped onto the dead log, his arms wide for balance, a perfect crucifixion in motion. At the same time, McFadyen stooped and scooped up a good-sized rock, swung hard, and brought the rock down against the back of Jamie Kier's skull. Kier fell from the log into the stream. McFadyen knelt down upon the young boy's back and held his face in the flowing stream until he stopped breathing.

McFadyen took the vest off the dead boy and put it on himself, patting the money pocket and grinning at the jingling sound it made. Then he searched the boy's belongings and took whatever seemed valuable. He heaped some fir boughs over the boy's body, and left him lying there in a quiet glade beside the happily rattling stream. He stood up, said a small prayer over the boy's makeshift grave, then walked away from the scene of the murder, whistling and grinning to his wicked old self.

By the time Neil McFadyen reached his home, he had begun to have second thoughts about his actions. “Secrets never stay kept,” he told himself. “And a murder will out itself, as sure as sin has got whiskers.”

The fear of having his guilt discovered gnawed away at McFadyen's uneasy conscience. Before the week had run its course, Neil McFadyen had allowed his guilty paranoia to run wild over his imagination. He barred the windows and reinforced the cabin door. He carried a large basket of rocks, just perfect for throwing, into his house. He bought himself a pitchfork, which he set by the front door. He likewise kept a loaded long rifle hanging over the fireplace. “If they come for me,” he thought to himself, “they'll have a fight on their hands.”

His wife and children grew fearful at his behavior. “Is the devil after you?” his wife asked. “What have you done now?”

McFadyen said nothing.

The days passed into weeks, and it seemed as if Neil McFadyen was destined to get away with his evil deed. In spite of this, his paranoia grew continuously. He would sit in an old wooden rocking chair and watch his front door intently, as if he was terrified that someone or something was going to walk in unexpectedly and accuse him of the murder. And then, suddenly, that is exactly what happened.

In late September

1848

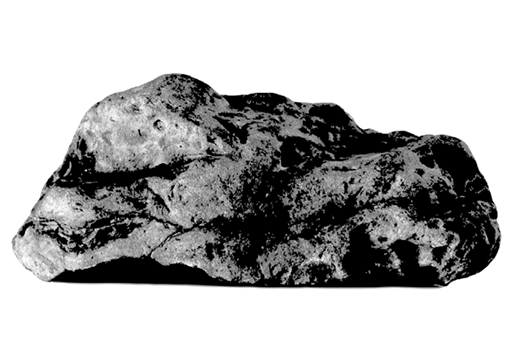

, two months after the murder of Jamie Kier, a local hunter stumbled across Kier's remains. It was not a pretty sight. The flesh had rotted past recognition. Insects, rodents, coyotes, and birds of prey had fed upon the flesh while it was fresh, and then decomposition had continued until parts of the body were worn to the bone. What was left of the flesh was blackened and nearly unrecognizable.

Word went out, and shortly afterwards, Jamie's father and brother arrived from New Brunswick. They had long suspected that Jamie had come to a bad end, and had reported him as missing to any authorities who would listen.

The body, unfortunately, was unidentifiable. The few remaining rags of apparel provided some clue to the corpse's actual identity; however, it was Jamie's father who gave the authorities the vital clue they required to verify the corpse's identity.

“There is a small, hard lump on the inside of his left jawbone,” Jamie's father said. “It is a souvenir from a horse that kicked him when he was a young boy.”

The advanced state of decomposition made easy transport a virtual impossibility, but medical examiners severed the head, placed it in a basket, and transported it to a proper facility. Once there, a team of three doctors cut into what was left of the jaw and found the telltale lump. “Without a question,” the medical team reported, “given what we have been told, the remains discovered in the Moose River woodland belong to Jamie Kier.”

Further investigation led back to the New Brunswick logging camp, where it was verified that Jamie Kier had indeed spent an inordinate amount of time in the company of Neil McFadyen. “They left together,” the logging foreman reported. “The two of them quit on the very same day and sailed off for Nova Scotia.”

Following this testimony, a legal warrant was sworn out. It happened fast. Neil McFadyen was taken completely by surprise. He wasn't even given the time he needed to reach for his pitchfork, his rocks, or to even try for his long rifle, when local authorities arrived to search his cabin. They uncovered Jamie Kier's vest and several of his personal belongings. McFadyen's wife and children stood by, amazed and terrified, as Neil McFadyen was promptly arrested and charged with the murder of Jamie Kier.

McFadyen spent the next two months brooding in a cold and lonely jail cell in the jailhouse directly beside the Pictou courthouse. Following a short trialâin which the severed head was reportedly brought into the courtroom in a wooden box of salt as a piece of necessary evidenceâNeil McFadyen was convicted, and sentenced to be hanged on Wednesday, December

20

,

1848

, somewhere between the hours

10

:

00

am

and

2

:

00

pm

.

McFadyen was taken by horse-drawn wagon to the Hospital Point beach. He sat upon a crude wooden casket that would serve as both a platform and the ultimate resting place for his remains.

It was a brutally cold morning, with a stiff Atlantic wind blowing in directly across the beach. A crowd of at least fifty onlookers braved this cold, and followed along behind the wagon until they came to a properly sized beach pine that had been chosen for the procedure.

The sheriff stood on the wagon beside McFadyen as he carefully arranged the noose. Neil McFadyen wore nothing but a thin jacket and a tattered shirt and pants.

“It's mighty cold out here,” McFadyen complained to the sheriff. “If you are going to do it, then you might as well put me through at once.”

“No sir,” the sheriff said gruffly. “I will see this done as the letter of the law prescribes. I dare say it was equally cold in that hole you left young Jamie Kier to rot in, and I dare say it will be warmer where you are going soon.”

Some of the onlookers voiced their objections, maintaining that a swifter execution might be in keeping with the custom of following a condemned man's last request, but the sheriff only turned his face stubbornly into the wind and waited the objections out.

Promptly at ten o'clock, the sheriff stepped down from the wagon, leaving Neil McFadyen standing on his own coffin with his neck in the noose. The sheriff picked up a short leather whip, with which he cracked the horse's hindquarters, and before you could say “drop,” Neil McFadyen was twisting in the wind.

They cut McFadyen down after a doctor pronounced him dead. A party of four volunteers dug a hole in the sand on the beach, and then they buried Neil McFadyen there in an unmarked grave.

As for Jamie Kier, he was buried in the Pioneer Cemetery on Sutherland's Mountainâlocated just south of Blue Mountain in Pictou County, along Route

347

.

A small stone monument was erected, and still remains standing over his grave, engraved with the following inscription:

In Memory of

James Kier

A Native of Bay D'Chaleiu

Aged

21

yrs

Who came to his death the

1

st of July

1848

by the hands of an assassin