Margaret St. Clair

Read Margaret St. Clair Online

Authors: The Best of Margaret St. Clair

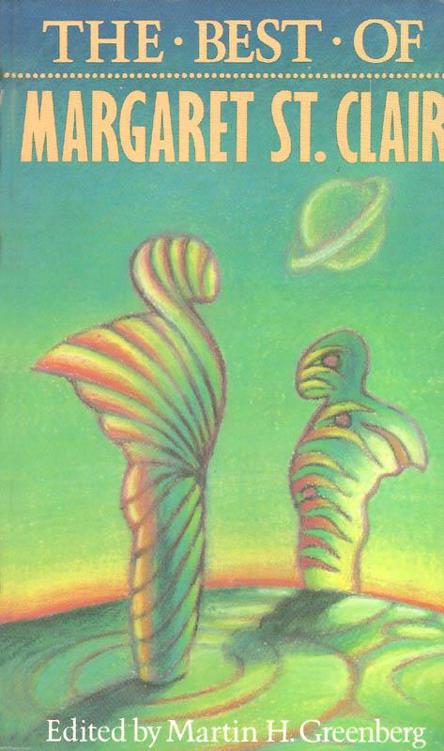

The Best of Margaret St. Clair

(1985) *

Margaret St. Clair

Contents

Introduction:

Idris’ Pig

The Gardener

Child Of Void

Hathor’s Pets

The Pillows

The Listening Child

Brightness Falls From The Air

The Man Who Sold Rope To The Gnoles

The Causes

An Egg A Month From All Over

Prott

New Ritual

Brenda

Short In The Chest

Horrer Howce

T

he Wines Of Earth

The Invested Libido

The Nuse Man

An Old-Fashioned Bird Christmas

Wryneck, Draw Me

Book information

Introduction:

Thoughts From My Seventies Most of the sense impressions of my childhood were pleasant. The fruit —winey, crisp Jonatha n apples, luscious slip-skin purple concord grapes, tomatoes hot from the sun and full of ripe red juice —was the soul food of my childhood. I remember the taste of Mallard ducks —too pretty to kill, with their lovely plumage, but luscious eating —dome

s tic chicken, and wild squirrel. I loved a kind of butterscotch sucker, embossed, improbably, with a duck, and a cool, vanilla-tasting, cream “club soda.”

Things had more flavor then, and there is more than the usual blunting of the senses with age involv ed in my thinking this. The sophisticated food-handling techniques of the present had not yet been devised. The Sunday fried chicken had, only a few hours earlier, been pecking melon rind in its pen. The food of my childhood tasted better because nobody k n ew how to make it stay edible —free from gross spoilage —for six months.

The flowers had wonderful smells. Sweet peas were intoxicatingly sweet, so that the room seemed to rock and reel with their perfume. Peonies —red, pink, and white —smelled of so fter, cooler roses. The heavy, intoxicating trusses of purple lilacs lasted poorly when cut, but oh, how choice they were among the flowers in a May basket! I loved lily of the valley, citrus-smelling silver bells, Keats’ valley lilies. There were plenty o f good things to taste and smell when I was a child.

Emotional pleasures were another thing. Human warmth was not in good supply. But my two uncles, Uncle Ross and Uncle John, were darlings. I wasn’t an articulate child, and I hadn’t been taught good man ners. I don’t know whether they ever knew how much I appreciated all their kindnesses to me. I shall always remember them with gratitude and affection. Two dear, land, men, loving and, I fear, rather unhappy —wherever they are now, I wish them happy, and I wish them well.

The road from loving uncles in Kansas to science fiction writing in California is a tortuous one and one that I don’t want to try to retrace. John Clute, who did a critical study of my work in Science Fiction Writers, characterized me a s “elusive”, and it may be so. Certainly I dislike writing about myself. The reason for this, I think, is that I am often uncomfortably aware of my not having “the right attitude”. (Do youngsters nowadays get chewed out for not having “the right attitude”? I imagine they still do.) I am conscious of having, no matter what group I’m in and no matter how stoutly I embrace their principles, some mental reservations. For example, I’ve been interested in the work of the American Friends Service Committee since 1945. Yet I do wonder whether the death penalty is always wrong. I’m a longtime civil libertarian, but sometimes the ACLU does things that I wonder about. And so on. In short, I’m never really a true believer, although I do believe. My political sympathie s, as Mr. Clute observed, are with the democratic left.

Where science fiction is concerned, I am often puzzled by the intensity of feeling people bring to it. Is it a sacred cause? Have science fiction writers become the seers, the prophets, the moral te achers, of our age? Can they give us guidance on levels unknown to the writers of detective or gothic fiction? I don’t find the qualifications for these elevated roles among my colleagues or in myself.

The genre of science fiction writing has much to rec ommend it to a writer. The freedom that prevails in it is unique, it commands more public respect than other forms of popular fiction, and it is possible to sell it fairly frequently. And the heady action and excitement that are typical of it make it grea t fun to write.

It has disadvantages, too. It never pays very well, the science in it has a short shelf life, and attempts at humor and characterization in it are apt to make a piece less saleable and cost the writer dear. Its predictive and prophetic val ue, in which public respect for science fiction seems to be rooted, have not proved very great. And yet I wrote a lot of it.

I wrote a lot of it, and I certainly wasn’t well paid. I enjoyed it; I didn’t get much approbation. I have been far more successf ul as a writer abroad than in this country, but this came late. What was I up to? What were my colleagues up to? If science fiction doesn’t predict, and really can’t act as moral authority, is it nothing but entertainment? What, in short, is science ficti o n all about?

The Marxists of the thirties used to talk of the “historical task” of capitalism. (It was to develop the productive capacities of mankind, in case you’re interested.) Has science fiction had a historic task to perform, albeit an unconscious one? Is an intuition of this why people are interested in it?

Forgive me for all the rhetorical questions. I think I can answer them, at least to my own satisfaction. The historic task of science fiction is to develop a global consciousness.

This is th e task of our age; to rise above our petty jealousies and hatreds, to learn to use our admirable local loves and loyalties as the binding cement in a larger loyalty. We must learn to think of ourselves as the inhabitants and citizens of the third planet f r om the sun.

Who, having seen the pictures of our earth from space, could forget them? That cloudy opal, incomparably beautiful, incomparably precious, dear beyond any other dearness —earth, whose fate now lies in our merely human hands.

I have just di savowed pretensions to being a prophet or a seer, and now I am talking like one. Yet there is a difference. It is one thing to point out goals for humanity —“tomorrow the stars” — and another to contribute to the realization of a fact: that we live on a f ragile, destructible planet. We have only one earth.

They say the aging eye is far-sighted. I am now in my early seventies. The thing I see most clearly is that this age confronts us with the task of learning to think of ourselves as a global people. Whe n our deepest loyalties will have been given to our planet, we will have begun to be safe on earth.

-

Those who have lived through the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Coventry, Dresden, may be excused for forgetting that love, kindness, compassion, nobility, exis t. Yet in man’s animal nature lie not only the roots of his cruelty, viciousness, sadism, but also of his perfectly real goodness and nobility. The potential is always there. It is the task of our age to make it actual.

It may be that science fiction wri ters, without ever being conscious of it, have been moved as a group to blow on the spark of a new awareness in human beings: that we live on a sacred planet.

If anything I have ever written will have contributed to that goal, I am well content. Other ag es will have other tasks. Our task today is to realize that we live on, and are citizens and lovers of, the third planet from the sun, the ultimately sacred earth.

Margaret St. Clair September, 1985

-

Idris’ Pig

“Do you have to talk so much, gesell?” Bill begged hollowly from his bunk. His face, which had turned pale at the Cyniscus’ take-off two days before, was by now the pale curded green of a piece of bosula cheese, and his eyes were sunk. “It sounds as if you were trying to keep yourself from thinking about Darleen. I don’t want to be ungrateful, but all that talk makes me feel worse.”

George shook his head. “Before you can get over your attack of kenoalgia,” he said remorselessly, “you’ll have to realize wh at’s causing it. There’s nothing wrong with you physically, but being in open space for the first time in your life is giving your ego the worst beating it’s ever had. The first spacemen, who weren’t trained psychologists, couldn’t believe that so much na u sea and prostration could have mental causes. They attributed it to a marasmic action of cosmic rays on nervous tissue, and the first two expeditions to land on Luna mutinied rather than go through ‘space scurvy’ getting home again.” He cleared his throat.

“Kenoalgia’s a new disease,” he went on, “because it’s a response to a new situation for the human organism, being out of Earth’s gravitational field. Psychologically, it’s a combination of repressed fear of falling, anxiety about bodily integrity, and the rejection response. The cure —say, do you smell something funny in here?”

Bill opened one eye and looked at him. “Uh-uh,” he said.

“Something sort of fishy and rank? No? Well, as I was saying, the cure —”

“Get out,” Bill said wanly, “Please get out. Go away and brood about Darleen. I don’t care if you are my cousin and the Cyniscus’ psychological officer, when you talk it makes me feel worse.”

Looking hurt, George began to unwind his long legs from the rungs of his chair. “You’re sure you don’t notice that smell?” he asked solicitously. “It might be adding to your nausea.”

“Don’t smell a thing,” Bill replied firmly. “You’re imagining it. Oh, by the way, could you turn the projector on before you go? No. 9, Blue Disks, is my favorite. It seems to help my giddiness.”

“Sure.” George made the adjustments. A galaxy of blue and purple disks appeared on the wall opposite Bill’s bunk. Motionless themselves, they blinked on and off in a succession of patterns that might, George conceded, be soothing t o kenoalgia dizziness. “Anything else I can do for you?” he asked, lingering.

“Call the medical officer.”

“No sense in that. Kenoalgia is purely —”

“Psychological. I know. Get out.”

When the door had closed, Bill, looking very sick and very, very r esolute, got out of his bunk. He tottered over to the little brown box which stood on top of his Travelpak, and gave an anxious sniff. An expression of consternation came over his face. He sniffed again. Then he got a deodorant spray out of his bureauette and went over the box with meticulous care, stopping only when his sense of smell told him all was sweet once more. Gaunt and shaking in his long chicory-colored sleeping tunic, he crawled back at last into bed.

In the ship’s lounge, Mr. Farnsworth was talking to George. George had long ago divided all passengers into three groups: those who snooted you because you were one of the hired help; those who stood you drinks because you were, after all, one of the offi c ers; and those who kept leading the conversation around to psychoanalysis, hoping you’d do a little free work on them. Mr. Farnsworth belonged to the second group.

“Too bad I’m transshipping at Marsport,” the older man said expansively as the barman brou ght their drinks. “This is a big time of year for the Martians. I hate to miss the festivals.”

“Oh, is it?” George replied vaguely. He had accepted Farnsworth’s offer of a drink merely because he hadn’t known how to refuse it. What he really wanted was t o get down to his cabin and (not think about Darleen —certainly not) and look up an article in the Journal of Psychosomatokgy on new treatments for space scurvy. He was a little worried about Bill.