Margaret Fuller (7 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

Mariana takes to wearing her stage makeup on schooldays, dipping into “her carmine saucer on the dressing table” each morning to paint her cheeks, and the other girls, once tolerant of her eccentric dress—“some sash twisted about her, some drapery, something odd in the arrangement of her hair”—finally begin to tease her for it. Mariana persists in the habit, at first saying she likes to “look prettier” and then responding with silence. The detail has the ring of painful truth, as if Margaret, not nearly so reconciled to being “bright and ugly” as she’d vowed, had adopted the same routine herself at Miss Prescott’s, wishing to cover her acne. One day at dinner, Mariana looks up from her plate to see that the other girls have all painted large circles of rouge on their cheeks; they laugh at her down the table as teachers and servants look on with barely suppressed giggles.

Mariana maintains her composure through the meal, relying on her “Roman” spirit to carry her through the ordeal. But she collapses in hysterics afterward in her room, only to rise up transformed. She cannot forget that not one of her former companions took her side by refusing to take part in the prank. Her outward “wildness, her invention” are gone, replaced with somber studiousness and a sudden interest in the other girls’ gossip, which she cleverly manipulates until those who have wronged her are consumed with jealousy and spite. She has become a “genius of discord” rather than a genius of the imagination. And then she is found out, accused—rightly, she admits—by the older girls of “calumny and falsehood.” The “passionate, but nobly-tempered” Mariana throws herself on the floor, dashes her head against the iron hearth in shame. She knows that by seeking vengeance she has committed a greater wrong than those who injured her first.

It is left to the headmistress to calm and console Mariana—and she does so as Ellen Kilshaw might have: by expressing complete sympathy and confiding errors from her own youth. “Do not think that one great fault can mar a whole life,” she exhorts Mariana. The girl is changed again, “tamed in that hour of penitence”: “The heart of stone was quite broken in her. The fiery life fallen from flame to coal.” Mariana asks her schoolmates’ forgiveness, and they accept her as a “returning prodigal.” She emerges from this “terrible crisis” as one who “could not resent, could not play false.”

Although Margaret’s account of Mariana is fictional, it derives from genuine suffering Margaret endured but never revealed to anyone outside the school. Five years after she left Miss Prescott’s academy, she was still writing to her teacher of “those sad experiences,” which continue to “agitate me deeply.” And still grateful to Miss Prescott, “my beloved supporter in those sorrowful hours.” Her memory of “that evening subdues every proud, passionate impulse,” Margaret wrote: “Can I ever forget that to your treatment in that crisis of youth I owe the true life,—the love of Truth and Honor?”

Margaret’s tale of Mariana has many elements of popular morality tales of the time: a high-spirited, nonconforming girl is “tamed,” inducted into womanhood and its gentler ways. Yet Margaret’s story has a twist. Mariana’s “fiery life” may have “fallen from flame,” but it is not extinguished: the embers remain, banked coals that burn steadily or may be reignited. The lesson she learns is not submission but perseverance when faced with ill will, and authenticity: she “could not resent, could not play false.” These are the qualities Margaret thanks Miss Prescott for in her letter: “the love of Truth and Honor.”

Whatever transpired at Groton, and between Susan Prescott and Margaret Fuller, left the girl stronger and steadier of purpose when she returned home for her fifteenth birthday. Margaret’s first letter to Susan Prescott from Cambridgeport told of following a rigorous course of language studies—reading French and Italian on her own for several hours each day, morning classes in Greek—along with metaphysics, piano practice, regular walks, and evening journal writing. “I feel the power of industry growing every day,” she wrote, driven by the “all-powerful motive of ambition.”

If Timothy had hoped that a year at boarding school would help focus Margaret’s sights on the domestic sphere, he was wrong. “I am determined on distinction,” she confided in Miss Prescott, “which formerly I thought to win at an easy rate; but now I see that long years of labor must be given.” But she would not be one of those “persons of genius, utterly deficient in grace and the power of pleasurable excitement.” Rather, “I wish to combine both.”

She was still the Margaret who yearned for power and influence, and for someone to share it with—who, as she wrote Miss Prescott again three years later, was capable of feeling “a gladiatorial disposition” along with “an aching wish for some person with whom I might talk fully and openly.”

• II •

CAMBRIDGE

Margaret Fuller, sketch by James Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke, sketch by his sister, Sarah Freeman Clarke

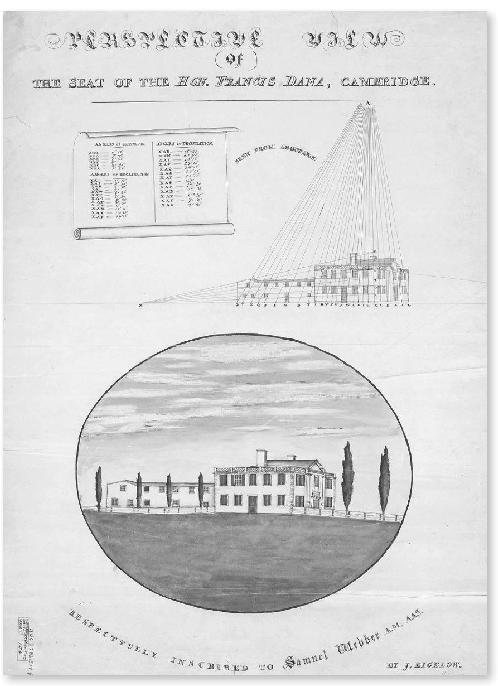

The Dana mansion, Cambridge

5

The Young Lady’s Friends

I

T WAS BACK IN CAMBRIDGE THAT MARGARET ENCOUNTERED

the “dignitaries” she later wove into her story of Mariana. She had been away at Groton in August of 1824 when the marquis de Lafayette arrived in Boston at the start of a triumphal American tour, which drew grateful crowds to roadsides everywhere he passed. Now, in June of 1825, the aged hero of the American Revolution was back in the city again, preparing for his return to France, and Margaret was allowed to tag along with her parents to an opulent reception hosted by Boston’s mayor, Josiah Quincy. The fifteen-year-old girl insisted on making her own introduction, by way of a letter composed earlier that same day.

“I expect the pleasure of seeing you tonight,” Margaret began. Though she admitted to being only “one of the most insignificant of that vast population whose hearts echo your name,” she could not “resist the desire of placing my idea before your mind if it be but for a moment.” The idea of Margaret Fuller: already she sensed herself to be a significant personage, as much idea in the minds of others as reality to herself. She wished to tell him, “La Fayette I love I admire you”; and she wanted him to know how much his example inspired in her “a noble ambition.” This was a fan letter, and an “ardent” one (the word peppered her letters now), but self-deprecation had vanished by the closing line: “Should we both live, and it is possible to a female, to whom the avenues of glory are seldom accessible, I will recal my name to your recollection.”

Whether her letter reached Lafayette in time, or whether Margaret managed the personal encounter she hoped for, is not known and does not finally matter. What matters is this: even at fifteen Margaret could not contemplate glory without placing herself in its presence. Yet she had also begun to confront the inevitable difference between her future prospects and those of a similarly talented, nobly ambitious boy. Was it “possible to a female” to wield power? And if so, how?

Contemplating the heroic example of the Greeks in an essay written for her father was one thing:

They can conquer who believe they can.

She could imagine herself into that earlier world as, perhaps, an Amazonian warrior, or even as a member of Aeneas’s crew. Margaret’s mind could take her anywhere; she delighted, she wrote to her teacher Susan Prescott, in being “translate[d]” through her reading or in daydreams to “another scene,” where she became absorbed, “to tears and shuddering,” by the “spirit of adventure.” Most recently she had become immersed in the novel

Anastasius,

which “hurls you,” alongside its protagonist, “into the midst of the burning passions of the East.”

But at a formal social occasion for a living hero of her own day, the ritualized behavior and dress—the stark differences between dark-suited men and puffy-sleeved, corseted women as they sat at table, gathered after dinner in separate rooms—must have seemed incontrovertible evidence of feminine constraint. Was there “pleasure” to be had in Lafayette’s company that night for a girl like Margaret, who wished herself—willed herself—onto the avenues of glory with the likes of her hero?

The following year, in support of Timothy’s ambitions for himself and for Margaret—could they be separated?—the Fullers moved into the former home of Chief Justice Francis Dana, giving up their drab Cambridgeport house for a grand Georgian residence perched on a terraced hillside in Old Cambridge, a quarter of a mile east of the Harvard campus. With a private drive leading up from the road to Boston across spacious lawns dotted with specimen fruit trees, the Dana mansion offered an expansive view over the Charles River, “so slow and mild,” Margaret wrote. From her second-story window she could see all the way to the “gentle” Blue Hills of Dedham in the south and to Mount Auburn in the west, which glowed in the late-afternoon sun beyond the slate rooftops of Harvard’s handful of classroom and dormitory buildings.

The prospect was far superior to the Cambridgeport soap works, which her four-year-old brother Arthur, lording it over the two younger Fuller boys, Richard and the new baby, Lloyd, in the nursery at Dana Hill, mischievously claimed to miss.

But the greater luxury only highlighted Margaret’s increasingly ambiguous position in the family as she neared adulthood. What was she to do with her prodigious learning and restless ambition? At sixteen, she was now the eldest of seven Fuller siblings, with the cherubic six-year-old Ellen her only sister. Had she been a boy, Margaret would have begun classes at Harvard. Instead she was required to start the little ones on their first lessons and hear daily recitations from Eugene and William Henry, ages eleven and nine, while pursuing an ambitious self-imposed curriculum of her own devising. Most days she made time for Greek and Italian language study, French philosophy and literature, and piano practice—all preparation for an only dimly foreseeable future in which marriage was the sole achievement expected of her, but the last thing on her mind. No wonder she allowed the rosy sunset over Mount Auburn to draw her attention away from Harvard’s imposing brick and stone campus: she could never walk those avenues of glory as a scholar or, as might one day have been appropriate to her talents, professor.