Margaret Fuller (56 page)

Authors: Megan Marshall

Margaret would always treasure the handful of letters she received from Mazzini that June, letters written “for you only.” But Mazzini was also accounting for his actions in anticipation of Margaret’s book. “My soul is full of grief and bitterness, and still, I have never for a moment yielded to reactionary feelings,” he wrote to her, refuting rumors spread by the French that he had ordered the placement of mines on the grounds of St. Peter’s. He described settling disputes between officers and generals, nightlong strategy sessions, and watching at the bedside of a friend, “a young soldier and poet of promise,” who could not be saved.

On June 28, as bombs “whizzed and burst”

near Margaret’s Casa Diez, and thirty fell on Lewis Cass’s residence at the Hotel de Russie, Mazzini wrote: “I don’t know whether I am witnessing the agony of a Great Town or a successful resistance. But one thing I know, that resist we must, that we

shall

resist to the last, and that my name will never be appended to capitulation.”

Mazzini argued before the assembly that the entire “Government, Army and all should walk out of Rome” to set up a government in exile in one of the mountain towns beyond the city. He sent Margaret a copy of his “protestation” to document his effort, but the assembly rejected the plan and Mazzini resigned his post as triumvir rather than concede defeat.

Garibaldi appeared before the assembly too, in blood-spattered uniform, refusing to continue what had become a fight for each city block. Garibaldi also advocated relocating the government to the mountainsides—“Wherever we go, there will be Rome!”—but he could not gain enough support.

Garibaldi made the heroic gesture on his own, gathering what remained of his army—four thousand men—and marching out of Rome on the afternoon of July 2 as the French prepared for occupation the following day. Margaret followed the regiment along the Corso and on to the city’s southern gates, beyond the broad piazza at the Basilica of St. John Lateran. She watched as the men, still “ready to dare, to do, to die,” passed in waves, parted only by the ancient Egyptian obelisk at the center of the piazza, the oldest and tallest monument in Rome, scavenged fifteen centuries before from Karnak.

“Never have I seen a sight so beautiful, so romantic and so sad,” Margaret wrote for the

Tribune.

“The sun was setting; the crescent moon rising, the flower of the Italian youth were marshaling in that solemn place.” Wearing bright red tunics and carrying their possessions in kerchiefs, their long hair “blown back from resolute faces,” Garibaldi’s men marched behind their leader as, high on his horse and dressed in a brilliant white tunic, he took one glance back at the city, then ordered them onward through the gates. “Hard was the heart, stony and seared the eye,” Margaret wrote, “that had no tear for that moment.”

Garibaldi’s Brazilian wife, Anita, an expert horsewoman who had fought with the legion, rode beside him, pregnant—although Margaret mentioned nothing of it in her account—and suffering from malaria. On this quixotic last mission, chased by the armies of all the nations opposed to the Roman Republic, Garibaldi’s legion would dwindle to a handful. Anita died in his arms within a month of their proud exodus.

On July 3, French troops claimed the city, marching “to and fro through Rome to inspire awe into the people,” Margaret wrote, “but it has only created a disgust amounting to loathing.”

The assembly had not decamped to the mountains, but the deputies would not surrender easily. Instead they kept their seats, reading aloud once again the provisions of the new constitution, voting in measures to aid the families of the dead and awarding citizenship to any who had defended the city, until French soldiers entered the chamber and ordered the deputies’ removal. Margaret had dreaded this day and “the holocaust of broken hearts, baffled lives that must attend it,” as she’d written in the

Tribune.

But what she had seen was bravery.

“It is all over,” Mazzini wrote in one of his last letters to Margaret. He wandered the streets of the city for most of a week, at liberty, it seemed, because the French did not want to make a martyr of the failed republic’s greatest hero. Now it was Margaret’s turn to procure a false American passport for a Roman citizen, asking the favor from Lewis Cass, so that Mazzini could travel safely into exile once more. She would secure another for Giovanni; the couple would make a trip to their son’s home, their first one together.

“But for my child, I would not go,” Margaret told Lewis Cass.

She worried about the Roman soldiers still in the hospitals, “left helpless in the power of a mean and vindictive foe.”

Margaret had not completed her “observations” either. One day in early July, soon after the fighting ceased, she walked the deserted battlefields outside the city, surveying the ruined villas. One of the

contadini

showed her where a wall had crumbled, burying thirty-seven republican soldiers, after just one cannon blast. “A marble nymph, with broken arm” looked on sadly from her fountain, empty of water. Farther on, Margaret studied the terrain held by the French, “hollowed like a honey-comb” with trenches. “A pair of skeleton legs protruded from a bank of one barricade,” she reported, giving the “plain facts.” A dog had scratched away the soil to uncover a man’s body, fully dressed, lying face-up. How Margaret felt, she did not say: “the dog stood gazing on it with an air of stupid amazement.”

The dead had not yet been counted, but of the many soldiers who lost their lives in the bloody June days of the Roman Republic, three thousand would be buried in the shade of the cypress trees of the Cimitero di Santo Spirito.

“Rest not supine in your easier lives,” Margaret exhorted her readers in a final

Tribune

letter from Rome. “I pray you

do something;

let it not end in a mere cry of sentiment.”

To Richard she wrote, “I shall go again into the mountains,” giving yet another oblique explanation of her plans. “Private hopes of mine are fallen with the hopes of Italy. I have played for a new stake and lost it.”

• VII •

HOMEWARD

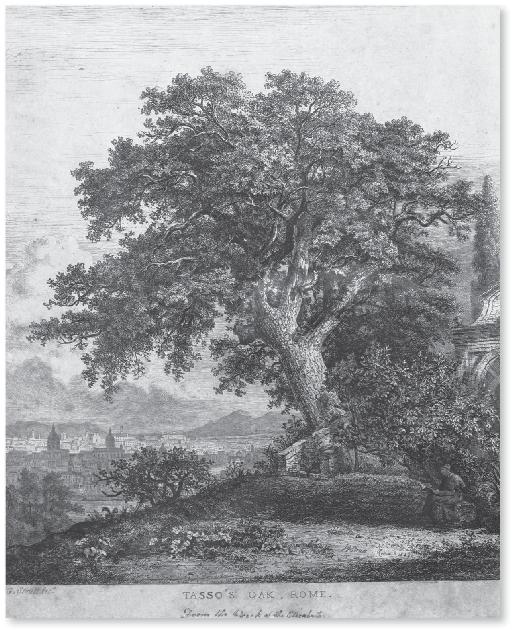

“Tasso’s Oak, Rome,” engraving by J. G. Strutt belonging to Margaret Fuller, inscribed “From the Wreck of the Elizabeth”

20

“I have lived in a much more full and true way”

N

INO WAS NO LONGER “PERFECTLY WELL” WHEN MARGARET

arrived in Rieti. Had it not been enough to fear for Giovanni’s life? On the night of the fiercest bombardment, when she had lain “pale and trembling”

on the sofa in her “much-exposed”

apartment, knowing that Giovanni was commanding a battery on the Pincian Hill, the most vulnerable position in the city, Margaret had vowed she would not spend another anxious night alone under fire. She arranged for Giovanni to come for her at the ringing of the Angelus the next evening and lead her to the Pincian gardens, now shorn of their towering oaks, preferring to die with him if they must. There she found many of the soldiers’ wives already camped with their husbands. Spending the last night of the Roman Republic with Giovanni, making no secret of their connection among his comrades, may have helped Margaret begin to frame the revelations she would soon make to friends and family—“I have united my destiny with that of an obscure young man,” she began one of them.

The morning after that surprisingly peaceful night on the Pincian Hill came the assembly vote to surrender, and with it the imperative for republican soldiers to evacuate the city. Giovanni could no longer safely lead a separate life in Rome.

Through the weeks under siege, Margaret had often imagined she heard Nino crying for her “amid the roar of the cannon.”

And now here he was, the Young Italy that remained for Margaret and Giovanni, “worn to a skeleton” when they reached him in mid-July, “all his sweet childish graces fled.” Nearly a year old, the boy was so weak he could barely lift the hand that Margaret reached out to kiss: “this last shipwreck of ho[pes] would be more than I could bear,” she wrote to Lewis Cass of her fear that Nino would die in Rieti. The “little red-brown nest” of a village had seemed so healthful, the air so pure; even the garrisoning of Garibaldi’s regiment in the town, once the stuff of nightmares for Margaret, turned out to have been the occasion for festivities, with the monks of the nearby monastery breaking their code of solitude to invite both Giuseppe and Anita Garibaldi in for “excellent coffee.”

But according to “the cruel law of my life,” Margaret despaired, the safe haven threatened to become Nino’s “tomb.”

And if so, she wished to die there with him, this “dearer self,” her son.

Margaret already knew what it meant to have a beloved infant—her little brother Edward—die in her arms.

Margaret had not fully understood the risk of leaving Nino with a wet nurse. She believed that by spending his infancy in the country town the boy would become “stronger,” “better than with me.” But the practice had never been common in New England and was increasingly out of favor in Europe, where mothers who were unable to nurse their newborns, or could afford not to, might still hire a nursing mother to live with the family; but they rarely sent infants away to the countryside.

Experience warned of just what happened to Nino. Chiara’s milk had slowed after nine months of nursing both Nino and her own child, and without Margaret on hand to supervise, Chiara had chosen in favor of her baby, weaning Nino onto bread and wine, pacifying him with the wine while withholding vital nourishment. The interruption of payments during the two-month siege probably forced the decision, which may have been ordered by Chiara’s husband, Nicola, who by spousal right collected the income from his wife’s breast milk. Margaret was appalled that Chiara had neglected Nino “for the sake of a few scudi,” but money was the basis of a transaction that Margaret recognized too late transformed “the bosom of woman” from a “home of angelic pity” into “a shrine for offerings to moloch.”

Wet-nursing in the Papal States followed rules dictated by the church. Some parents in villages like Rieti welcomed the extra income gained by raising another child alongside their own. But most wet nurses were unwed mothers, forbidden to rear their own children. Instead they were required by law to give up their babies at birth to foundling hospitals; permitting such women to nurture their own children was thought to lead the infants into sin. Knowing that local police would eventually confiscate their babies, many unmarried pregnant women took refuge in the foundling hospitals several months before giving birth and stayed there afterward, nursing other children, not their own, in exchange for lodging. Or, returning to their home villages immediately after the birth, they might hire themselves out, as did the young woman Margaret found next to revive Nino—a “fine healthy girl” with “two children already at the Foundling Hospital,” yet who, to Margaret’s frustration, was “always trying not to give him milk, for fear of spoiling the shape of her bosom!”

It took several weeks of feedings with the new nurse, who joined Margaret in the inn at Rieti where she now stayed with Giovanni, before the boy regained his “peaceful and gay”

nature. He remained delicate into the fall, when Margaret and Giovanni moved to Florence, bringing the wet nurse with them, to join the “American Circle” of expatriates there.

Nino had cried almost continuously those first weeks, “wander[ing] feebly on the surface between the two worlds”—life and death—perhaps suffering the effects of withdrawal from alcohol dependency.

In her travels across Europe and Britain, Margaret had instinctively sympathized with women, like the factory workers in Manchester, who felt compelled to sedate their hungry babies with opium during long days away, and she’d applauded the visionary schemes of the French Fourierists to provide infant

crèches

to the children of laborers, where mothers might feed their babies at intervals through the workday. But as Margaret had declared to her

Tribune

readers, “woman’s day has not come yet”

—not for Margaret or Chiara, nor for the “fine healthy girl” who saved Nino but was marked as a sinner and deprived of her own two children.