Margaret Beaufort: Mother of the Tudor Dynasty (9 page)

18. Margaret Tudor. Margaret’s eldest granddaughter was named after her and she was always a particular favourite of hers.

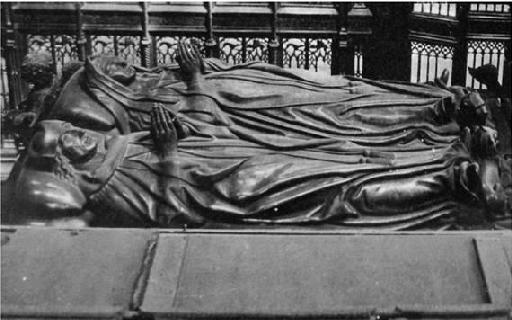

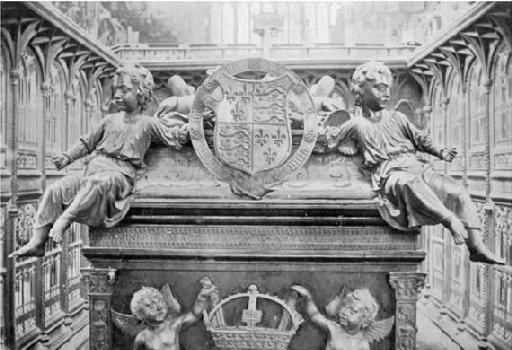

19. & 20. The tombs of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York at Westminster Abbey. Margaret was devastated by the death of Henry VII, her only child, and she survived him by only a few months.

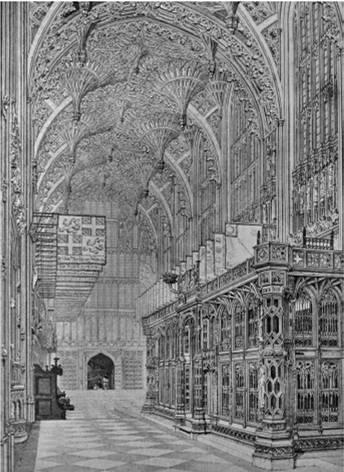

21. & 22. Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey. Henry VII commissioned a fine chapel in Westminster Abbey as his lasting memorial.

23. Margaret Beaufort’s tomb in Westminster Abbey. At her own request, Margaret was buried near her son Henry VII, in the chapel he built at Westminster.

24. Margaret Beaufort in later life. Margaret was well known for her piety and she chose to be depicted in a religious habit.

Henry Tudor, both as his mother’s heir and the potential heir to his father’s confiscated lands, was a particularly valuable child. William Herbert took him into his custody and was later granted the boy’s wardship for £1,000, a substantial sum and one that shows that Herbert was convinced of the future value of his young charge. Henry later told the chronicler Philip de Comines that ‘from the time he was five years old he had been always a fugitive or a prisoner’, and this certainly refers to his capture by Herbert at Pembroke Castle. If it was as a prisoner that Henry later came to see himself, it is unlikely that he was aware of this in 1461. Henry passed into the custody of Herbert’s wife, Anne Devereux, who treated him as one of the family, and he was raised in a manner befitting a young nobleman. It is clear from Henry’s own later conduct that he bore no grudge against his gaoler, and after he became king in 1485, Anne Devereux rushed to meet him. The meeting was obviously a success, and the King provided her with an escort for her return journey, highlighting that he must still have had some fond memories of his time with the Herberts, in spite of his later assertion that he was a prisoner. William Herbert and his wife also had a reason to invest their energies in Henry’s upbringing, as they had a number of unmarried daughters. In his Will, written in 1468, Herbert stated, ‘I will that Maud, my daughter, be wedded to the lord Henry of Richmond; Ann to Lord Powys; and Jane to Edmund Malafant; to Cecily, Katherine, and Mary, my daughters, MMD marks’. As a potential future son-inlaw, it was in Herbert’s interests to ensure that Henry was well raised regardless of the fact that, as a supporter of Edward IV who was granted Jasper Tudor’s earldom of Pembroke, he was fundamentally opposed to the interests of the Tudor family. Henry was well educated, and there is some evidence that the Herberts employed two Oxford graduates, Edward Haseley and Andrew Scot, for this purpose, again suggesting that his ‘imprisonment’ was not as rigorous as he later implied.

Although she knew that she had permanently lost any rights in relation to her son, Margaret must have been glad that he fared no worse, especially given Jasper Tudor’s continuing prominence with Margaret of Anjou and Henry VI in Scotland and the north of England. Margaret was also not barred from visiting Henry, and she and Henry Stafford kept in touch with him. They visited him at Raglan Castle in September 1467 when they were staying at their West Country estates. They made their way to the castle from Bristol and spent a week there. It is likely that the visit was the main reason for visiting the West Country, and it is clear that they were made welcome by the Herberts. Margaret apparently spent a happy week at the castle with her husband and son. The fact that the couple were able to accept William Herbert’s hospitality suggests that Margaret accepted his custody of her son, even if she was not entirely happy with it. The chronicler Edward Hall later provided a description of Henry Tudor when he was in his late twenties, and during rare visits during the 1460s, Margaret would have slowly seen her son start growing into the man he would later become:

He was a man of no great stature, but so formed and decorated with all gyftes and lyniamentes of nature that he semed more an angelical creature then a terrestriall personage, his countenaunce and aspecte was cherefull and couragious, his heare yelow lyke the burnished golde, his eyes grey shynynge and quicke, prompte and ready in aunswerynge, but of suche sobrietie that it coulde neuer be iudged whyther he were more dull then quicke in speakynge (such was hys temperaunce).

Henry Tudor, like Margaret, was of a small build and their portraits in later life show a marked resemblance: both with long, thin faces and keen, searching eyes. Although Margaret had had very little contact with her son since his infancy, she always ensured that they remained in touch, and he remained her greatest focus.

Whilst Margaret was concerned about her son’s welfare, she also had to ensure the welfare of her husband and herself following Edward IV’s accession. Edward IV had been nearly nineteen at the time of his accession to the throne, and having seen the Wars of the Roses lead to the deaths of his father, younger brother, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and a number of other members of his family, he was determined to be conciliatory in an attempt to bring the conflict to an end once and for all. Edward IV, whilst a shrewd ruler, was also a somewhat jovial character, inclined more to pleasure than politics. The new king had been received into London on a wave of public support, and a newsletter sent from London to Milan in April 1461 recorded that ‘King Edward has become master and governor of the whole realm. Words fail me to relate how well the commons love and adore him, as if he were their God’. Edward’s father, the Duke of York, had long been involved in a feud with Margaret’s uncle, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, and Edward IV was determined to prevent this continuing in the next generation, actively trying to make peace with Margaret’s cousin, Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. Somerset had travelled north with Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou following the Battle of Towton, but he finally surrendered to the King in 1462 and received an immediate pardon. Edward was determined to make a great show of his trust in Somerset, as demonstrated by

Gregory’s Chronicle

:

[Early in 1463] the king made much of [Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset]; insomuch that he lodged with the king in his own bed many nights, and sometimes rode hunting behind the king, the king having about him no more than six horsemen at the most, and three were men of the duke of Somerset.

Somerset’s apparent support for the Yorkist cause was a major coup for the King, and as further evidence of his determination to honour Margaret’s cousin, Edward decided to visit the north of his kingdom in the summer of 1463 and appointed Somerset and his men as his guards. According to

Gregory’s Chronicle

, the visit was not an entire success, and at Northampton, Somerset was attacked by the people as a traitor to the King. It was only with difficulty that Edward was able to save the life of his new ally, and this incident terrified Margaret’s cousin. Later that year, Somerset secretly left the King and once again headed north to rejoin Henry VI. He fought against the King’s forces at Hedgeley Moor on 25 April 1464 and again at Hexham on 14 May 1464, where he was defeated. Edward IV, although often kind and jovial, could be ruthless when he was crossed, and he had Somerset summarily executed following the battle as a warning to others that might plan to betray him.

Although Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, was the male head of the Beaufort family at the time of Edward IV’s accession, it was well known that Margaret was the hereditary heiress, and both she and Henry Stafford benefitted from the King’s intention to favour the Beauforts. They also soon had another link to the King when Edward, who had announced that he had secretly married a widow, Elizabeth Woodville, in 1464, married his sister-in-law, Catherine Woodville to Stafford’s nephew, the young Duke of Buckingham. Although both parties were children at the time of their marriage and it proved an unhappy union, it did serve to link Margaret and Henry Stafford to the powerful Woodville family and to the King himself, as did the fact that Stafford was a first cousin of the new King through their mothers.