Marching With Caesar - Civil War (82 page)

Read Marching With Caesar - Civil War Online

Authors: R. W. Peake

~ ~ ~ ~

For the Egyptian games, along with the gladiatorial contests, a large hole was excavated on the Campus Martius, then filled with water, making an artificial lake where naval battles were fought, using some of the ships from the Egyptian navy that were captured along with their crews, pitted against a small fleet manned by Tyrians. The Tyrians were chosen because they had refused to help Mithradates of Pergamum when he was raising a force to come to our aid in Alexandria, so their fate was to have some of their best young men chained to the benches of their ships and fight to the death for the enjoyment of Romans. The ships sailed all the way from Egypt and Tyre, then up the Tiber River to Rome. Finally, with the use of huge rollers and thousands of slaves, the vessels were manhandled across the open ground of the Campus to the artificial lake.

The endeavor had attracted a huge crowd of men from the army to watch, but the overriding sentiment was best described by Vellusius, who sniffed, “Well, we did that in Britannia and we didn’t have any slaves to help us. It was all our sweat that did it. What’s the big fuss about all this?”

With that, he turned away, followed by the rest of the men. I went with them as well; Vellusius was right. So much of what we were seeing constructed and done for this triumph that was done by slave labor in Rome had been accomplished by citizens in the army. I was noticing that I was picking up the attitude that most of the men, who in fairness had been in and around Rome for much longer than I had been, had about their fellow citizens. To the men of the army, our civilian counterparts were spoiled, soft, and incredibly lazy, and their attitude towards any type of manual labor engendered many a campfire discussion.

“They consider it beneath them, but it’s fine for anyone wearing a uniform to work as hard as a slave,” Glaxus spat into the fire shortly after our evening meal one night.

Scribonius was visiting, and Silanus was there as well, along with Balbus and Arrianus. There was a murmur of agreement at this, and I was one of those who agreed. Although I had not been here as long as the others, I had seen enough of the attitude to understand that it was indeed the prevailing one.

“It’s a load of

cac

is what it is,” Arrianus declared. “These civilians stick their nose up at us whenever we walk by, and you hear them making comments about what a soft life we’ve got sitting about in camp all day and night, just lolling about. Who do they think built this camp? Don’t they know a slave never digs so much as a spadeful of dirt building our camps? Or that the roads they walk on and that carry all those goods from every corner of the Republic were made by us and by the sweat off our back?”

“No, they don’t know that.”

I smiled, knowing that Scribonius could always be counted on to provide the other viewpoint.

All eyes turned to him, Arrianus scowling at Scribonius, who was whittling on a piece of wood, a favorite hobby of his. “As far as the people are concerned, all of what you speak of happens the same way that it happens in the city, by slave labor. Nobody has thought to tell them differently, so as far as they're concerned, we're no better than they are.”

“We’re much better than they are,” retorted Glaxus, raising another chorus of agreement. “We’ve sacrificed more, we’ve lost more friends than any individual citizen will ever have, all so that they can look down their nose at us when we walk by!”

“It’s our own fault, really.” Now I looked at Scribonius in surprise, while the others’ reactions were a bit stronger. I had understood and basically agreed with what he was saying, but now he was going into territory where I could not easily follow. “Think about it like this. How many people did we enslave out of Gaul?”

“About a million,” I answered.

Nodding, Scribonius continued, “And before that, how many slaves lived in Rome itself? Anyone know?”

We all shook our heads.

“I’m not sure either, but I think it was around 300,000, and I don’t have any idea how many in the rest of the Republic, but my guess is all told there were at least 1,000,000 slaves. Now in the space of seven years, we doubled that amount. How many people did we put out of a job?”

“You mean that they’re mad at us because we freed them from having to work?” protested Arrianus. “Why, they should be kissing the ground that we walk on.”

“Do you really believe that, Arrianus?” Scribonius asked quietly. “How would you feel if you could no longer provide for your family because you were replaced by someone who works essentially for free? Not because you did your job poorly, but merely because you needed enough money so that your family wouldn't starve? Would you really be grateful about that?”

All eyes turned to Arrianus, who was smart enough to know that he was on the losing end. “No, I suppose not,” he grumbled. “But it’s hardly our fault we’re so good at conquering people. What should we have done with all those Gauls? Thrown them back so we could fight them again?”

There was some laughter at this idea, as Scribonius admitted, “No, I’m not saying that necessarily. Honestly, I don’t know what the answer is, but I do know that it’s a little much to expect everyone to be happy with us for essentially taking away their livelihood.”

~ ~ ~ ~

Another five days of celebration passed before the third triumph, this one for the victory against Pharnaces, and again, just the men of the 6th marched. For the Pontic triumph, there was not as much to display, only a few hundred prisoners, and unlike with the Gallic and Egyptian, there were no high-born or prominent men to execute, so Caesar attempted to make up for it with wagons loaded with the arms and armor of the Pontic army that they had discarded fleeing from Zela. One of the pictures portrayed Pharnaces running away in his chariot, which seemed to be very popular with the crowd, but the one I favored the most was not a painting as much as it was an inscription. Caesar had his by-now famous words, “Veni, vidi, vici” written on one large canvas, and it was this that led the procession of scenes. I had thought that by the third triumph, the enthusiasm of the crowd would have waned, but this was not the case. Pontus had been an enemy of Rome for years, so the record of their defeat brought much joy and jubilation to the crowd. Of all the triumphs we celebrated, this was the least controversial, which was good because the final triumph was going to prove to be the most troublesome yet.

~ ~ ~ ~

As far as the men of the army were concerned, the last triumph was a bad idea from the moment it was mentioned. While our conquest of Gaul, along with the defeat of the Egyptians and Pontics was straightforward, we had fought our own people in Africa. Supposedly, the triumph was celebrating the defeat of Juba, and Caesar did parade Juba’s five-year-old son, also called Juba, though he did not have him wear chains and of course, he was not executed. He was actually treated very well, being raised as Roman. If things were left at that, there would not have been any problems, but Caesar could not content himself with only going that far. Several of the paintings depicted scenes that showed the assorted demises of Caesar’s enemies. Scipio was portrayed drowning at the hands of Sittius, Petreius in his duel with Juba and subsequent suicide, but I think the painting of Cato was the most distressing to the crowd. Caesar had spared no detail, showing both Cato’s initial attempt at suicide and the most grisly version of how he actually died. I have to say that whoever the artist was, he went to great lengths to show him pulling his guts out and throwing them about, so much so that even for a crowd as hardened to scenes of bloodshed as this, it was too much. The boos this time were loud and long, raining down on us from the crowd, causing us to look at each other with some concern. The crowd did not seem to be particularly inclined to violence, but with such a massive group of people, one never knew. I was marching back with the 10th, this time in my spot as Primus Pilus, so I was closer to the crowd and the expressions on their faces were ugly, their anger at the scenes that passed them by very raw and real. As we learned later, there was even more of a reaction from men closer to Caesar’s class than from those lining the streets. As Caesar entered the Circus Maximus, passing along the benches that were reserved for the Tribunes of the Plebs, all but one of them came to their feet as custom dictated. The man who refused to stand was one Pontius Aquila, which Caesar did not like one bit. There was an exchange of angry words between them, though I did not learn what was said, but while Aquila was the most visible in his disagreement with what Caesar had done, he was far from the only one. Still, Caesar was the undisputed master of Rome and the entire Republic, while the dissenters were in the vast minority and their protests little but a whisper, so if you had told me then what was to come, I would have laughed. There was still work to do, for both Caesar and the army, while many of us would be going home again as we had hoped, just not in the way we had planned.

Chapter 9- Munda

As the 20 days of festivities came to an end, it was not all good news for Caesar and by extension, the army. Pompey’s sons had escaped to Hispania after Pharsalus, where Pompey was still revered, his name carrying much weight with people. Almost immediately, two of the Legions, the men of the 2nd and Indigena, promptly declared for the sons of Pompey. Not helping matters had been the behavior of Quintus Cassius, who Caesar left behind as governor of the province three years earlier. He had been governor in Hispania before that, and during his first term acted with great avarice and cruelty towards the population. Apparently, he decided to pick up where he left off when he came back. I will not enumerate all of his crimes, but they were many and varied, the common belief being that he was his own worst enemy. He had died some time before, yet the rancor and bitterness he left behind was sufficient to make people throwing their allegiance to the Pompeys an easy choice. Caesar had left the 21st and 30th behind in Hispania and there was a

dilectus

for the 3rd Legion so it was full of raw youngsters. Commanded by Pedius, he was co-commander of the entire force with Fabius, but the 2nd, Indigena and the 1st, which had escaped once again, from Thapsus this time, was composed of veterans. Therefore, Caesar sent explicit instructions not to engage with the Pompeians. The Pompey brothers, Gnaeus and Sextus, were joined by Labienus, who just did not have the good grace to die, along with a number of other vermin who had managed to save their skins in Africa. The Pompey name created a stir of excitement in Hispania, culminating in the city of Corduba declaring for Pompey because of the crimes of Cassius, despite the fact that both were dead. About two weeks after the triumphs, at the morning briefing, we were given orders to make the men ready to march to Hispania, an order that was not unexpected, given all that we had heard about developments there, yet it was troubling nonetheless. When I was relaying the orders back to the officers of the 10th, there were a number of looks exchanged between the Centurions, but for several moments, nobody said anything.

Seeing this, I decided to speak up, as I was sure that the men were reluctant to voice their feelings, though I knew they were there. “I can see some concern with this order,” I began. “Anyone care to say why they’re worried?”

For a moment, I began to think that nobody was going to say anything and that I had misread the situation. Then Balbus cleared his throat. I had expected this from either him or Scribonius, or perhaps Horatius, who was not shy about speaking up.

“It’s just that we're marching back with all the other Spanish Legions,” he said. I did not understand his meaning, so I bade him to continue. “The 7th, 8th, and 9th are now several years overdue for their discharge, and yet they're marching home.”

“Have you heard anything?” I asked.

Balbus shrugged, clearly reluctant to say much more, but I was not about to let him off the hook.

He had opened his mouth, so now I stared at him until he finally replied, “Nothing definite, no. Just some grumbling about having to march home, but not being able to return to their families.”

“They will, once we finish up with the Pompeian whelps,” I protested, but the others were not moved.

It was Scribonius who spoke up next, and I knew that he was speaking for the rest when he said, “Primus Pilus, the men have been hearing that for almost three years now. I think that they’re past believing that it will actually happen.”

The rest of the men added their agreement to what Scribonius had said, as I found myself rubbing my face once more, trying to decide what to do about it. Some said that I should immediately send word to Caesar about what I had heard, yet I did not feel that there was anything specific enough that would warrant such a move. If I ran to Caesar every time the men complained about something, I might as well have brought my cot to set up in his headquarters. Besides, I reasoned to myself, Caesar had ears everywhere, so I had to believe that I would not be telling him anything he had not already heard himself. Once again, I was wrong.

~ ~ ~ ~

We packed up, marching away from the Campus Martius, the 5th, 6

th

, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and the 13th, marching rapidly west. The first few days were tough on everyone, a month of celebration and debauchery taking some of the iron out of us so that we had more than the normal number of stragglers, some of them not making it to the nightly camp until well after dark. The days were starting to get shorter, though the weather held for the most part, although there were a few squalls while we were marching near the coast. Caesar was remaining behind in Rome to finish some of his legislative work, along with his continuing consolidation of power, or else it might have been even worse for us if we had marched at his normal pace. It took us more than six weeks to reach the border between the two Hispanias, marching into the camp of Pedius, Fabius, and the three Legions under their command. By the time we arrived, all the fat and soft living was marched off of all of us, including me. It was shortly after we arrived, with the men busy setting up their tents in the area marked off for the use of the 10th that the concerns of my Centurions came to fruition.

“Primus Pilus, you're needed at the

praetorium

immediately,” came the summons from one of the Legionaries on headquarter guard duty.

I was about to give him a good thrashing because he had not announced himself properly and his salute was sloppy, but I could see that he was a youngster from one of the new Legions, probably the 3rd, huffing and puffing from running to find me, and completely scared out of his wits. Something was happening, so this youngster was going to escape a beating, though I do not think he realized just how lucky he was.

“What is it?” I snapped. “Why are you all out of breath like Cerberus is chewing at your heels?”

Gasping for breath, it took a moment before he could stammer out a reply. “I don’t know, Primus Pilus. It just has something to do with some of the other Legions. General Pedius has called for all the Primi Pili and Pili Priores immediately.”

“Which other Legions?” I demanded as I turned to grab my helmet and

vitus

.

“I don’t know, sir. I just know that some of them have deserted.”

I stared at him in astonishment, then quickly shook my head. He surely had it wrong, but I was never one to take my wrath out on helpless rankers unless it had some sort of value. Ignoring the rest of what he was babbling on about, I sent Diocles to round up the Pili Priores while I trotted over to headquarters. When I arrived, some of the other officers were already there, talking excitedly to each other. While some of the others seemed surprised, I noticed others with a look of resigned acceptance, and I hurried over to a small group standing in a corner.

“What’s happening?”

The Primus Pilus of the 5th, a tough old bird by the name of Battus, gave a harsh laugh, but there was no humor in it. “You haven’t heard then? Well, it seems that some of your fellow Spaniards have decided that they’ve had enough and are marching to join Gnaeus Pompey.”

I said nothing, sure that he was just having some sort of fun at my expense, but then I saw the grim expressions of the other men around him.

Finally finding my tongue, I asked, “How many and which ones?”

“It looks like it’s the 8th and 9th,” Battus replied.

“And the 13th, looks like,” a new voice added and I turned to see none other than Torquatus, old of the 10th and now the Primus Pilus of the new 3rd Legion.

“The 13th!” I exclaimed. “But they still have a couple years left on their enlistment. The 8th and 9th I can understand, they’ve been unhappy for a long time. But the 13th?”

Torquatus shrugged. “I don’t have any better idea than you, Pullus, that’s just what I heard General Pedius say.”

“Where are they now?” Battus asked.

Torquatus indicated the area out beyond the front gate. “Formed up and marching away. They stayed just long enough for their Primi Pili to come tell Pedius what they were going to do, then left.”

“Pedius should sound the call to arms and we should hunt them down and kill every last one of the bastards,” Battus said angrily, as a couple of his own Centurions added their agreement.

While I understood his feelings, I knew that this was not a good idea, on a number of different levels. “And who's going to do the killing?” I asked. “My men?” I continued before he could reply. “The men of the 7th? Men who have marched side by side, bled side by side, died side by side? You really think that the men will be willing to lift a sword against some of their closest friends?”

“And relatives,” added Torquatus, but Battus was unmoved.

“The men will do what we tell them to do, damn them,” he stormed. “They take orders, and if the General orders it, and I hope he does, then they'll do their duty.”

“Speak for yourself,” Torquatus retorted. “I’ve got nothing but green youngsters. That lot,” he indicated the cloud of dust marking the passage of the defecting Legions, “would take a lot of killing, and you should know that as well as anyone. And just because your boys took on some elephants, that doesn’t mean that they’re any match for those Spaniards.”

Battus’ face flushed with anger as he took a step towards Torquatus, who just stood there looking at him calmly.

Seeing that the situation was unraveling, I spoke up. “Battus, how many men are you willing to lose to keep them from marching away?”

Battus was still angry, and snapped, “As many as it takes.”

“Then who will be left to fight the Pompeians?”

That finally got through to him, as his mouth opened and closed a couple of times before he finally shook his head. “It’s just not right,” he muttered.

In that I had to agree with him, but I also did not want the rest of the army to mutiny, which I was sure would happen if we were ordered to try and stop them from marching away. Fortunately, Pedius had come to the same conclusion, which he informed us about once we were all gathered. He could not shed any more light on why the 13th had thrown in with the other two Legions, telling us that a dispatch had already been sent to Caesar, informing him of the defections. There was nothing much we could do except go back to our respective Legions, and of course by the time I returned, the men already knew what had happened.

I called a meeting of the Centurions immediately; as soon as they were assembled, I asked the question that had been pressing on my mind since I had heard. “Do we have anything to worry about?”

I was vastly relieved to see that all the men seemed to be in agreement that we did not.

“I’m just glad that the general didn't order us to try and stop them. That could have been ugly,” Scribonius said, and there was universal agreement about this as well.

“I don’t think he ever considered it an option, though I can’t say the same for some of the other Centurions,” I replied, then I was struck by a thought. “And now we’re suspect as well, because we’re Spaniards like the 8th and 9th. You need to impress on the men the need for them to keep their mouths shut about what happened and how they feel about it, at least if they’re sympathetic to their friends, which I suspect many of them are. The last thing we need is somebody from another Legion overhearing one of the men talking and having him accused of inciting a mutiny.”

It was not the best way to run an army, but I did not want a bad situation to become worse, and the Centurions all agreed that they would keep a tight lid on the men for the next few days.

~ ~ ~ ~

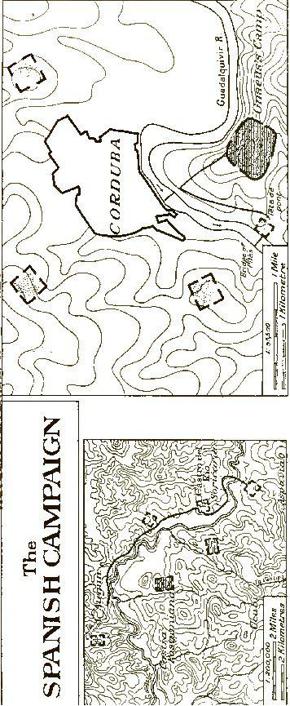

While Sextus Pompey was holding Corduba, older brother Gnaeus had decided to besiege the town of Ulia, one of the few in the region that still held for Caesar, but neither Pedius nor Fabius wanted to move until Caesar arrived. So we waited in camp, doing little more than conducting weapons drills, not even going out on forced marches because of the threat of ambush. We did run regular cavalry patrols, using native levies along with some of the men who had marched with us, thus keeping apprised of the enemy movements to a reasonable degree. Caesar wasted no time, taking just 27 days to travel what it took the army six weeks to cover, outrunning even his cavalry, which trailed behind several days. He arrived in early Januarius of the old calendar, which by this time was so far off being aligned with the seasons that it was still mid-autumn. Word of Caesar’s arrival spread quickly, and upon hearing it, a small party of elders from the town under siege managed to slip out to come to the camp, begging Caesar for assistance. In response, Caesar ordered three Cohorts of the 7th and three Cohorts of the 21st along with the same number of cavalry, under the command of a Tribune who had local knowledge by the name of Paciaecus, to leave shortly after dark, using the same route to enter the town as the elders had used to escape from it. In concert with that, Caesar ordered us to pull up stakes, then march on Corduba, the idea being that Gnaeus could not maintain a siege when his rear and base of supplies was under threat. As had so many of Caesar’s enemies, Gnaeus did not credit the idea that our general could move an army as quickly as he did, so before Gnaeus knew it, we were camped on the southern bank of the Baetis (Guadalquivir) river, just across from Corduba. Now Gnaeus had no choice but to lift his siege, hurrying to the aid of his brother Sextus. While Gnaeus was in the process of turning his army about and coming to confront us, Caesar put us to work building a bridge across the Baetis. There was already a stone bridge in place, but there was a fort guarding its northern side, which would have forced us to make a possibly costly assault, so instead, Caesar selected a site about a mile downriver to the south. We left a force of several Cohorts occupying a fort identical to the Pompeian fort on the north bank, the only difference being ours was on the southern bank, blocking Gnaeus’ army from crossing the river to get to Corduba. The bridge we built was a makeshift affair, constructed of baskets filled with stones, which we sunk to the river bottom to act as pilings. It was one of the shakiest constructions we had ever made while marching for Caesar, though it served its purpose. We crossed the river, then Caesar immediately disposed us into three separate camps, placing one to the west of the city, one to the north and one to the east, with the river serving as a barrier to the south. The 10th occupied the camp on the eastern side, which took us until past dark to finish since we had to build a camp in the face of the enemy. This type of camp is more strongly fortified while requiring more men to stand ready in case of attack. About mid-day the next day, Gnaeus’ army arrived on the other side of the river. Instead of immediately assaulting our fort and trying to force his way across the stone bridge, he chose instead to construct his own camp, siting it on a hill that rose up from the bend of the river that curved around the southern side of Corduba. This allowed Caesar to order a trench built that ran from our temporary bridge to our fort at the stone bridge that would allow us to send reinforcements to the fort under cover. The digging began immediately, and to Gnaeus’ credit, he did see that he had made an error, so he sent out a force of men that he could spare from the building of his camp to try to stop the work on the trench. There was a sharp fight, but after some hot work, our men repelled the Pompeians so that work continued. As this project was underway, Caesar and his engineering officers were surveying Corduba, yet even from my limited examination, I was not confident that we would be able to take the city easily. I had visited Corduba as a young recruit, but I had been too green to be able to assess the city’s defenses back then, not knowing what to look for. Now, almost 16 years later as I examined the approach and the walls on our side, I did not like what I saw. Fortunately, after his inspection, Caesar came to the same conclusion, so instead of trying to besiege the city, we spent the next several days trying to entice young Gnaeus to meet us in battle by forming up on the plain to the north of the city out on the open ground. The young Pompey was not biting, however; he was unwilling to put his mostly untested troops against the veterans of Caesar’s army. While Gnaeus may have had the three veteran Legions that defected from our army, he clearly did not trust them, because along with the 1st and the 4th, on paper that was more than enough to face us with a reasonable chance. After a number of days where we marched out to offer battle, only to be rebuffed every time, Caesar gave the order to break camp, our next objective being the fortress town of Ategua. It lies a day’s march to the southeast of Corduba, on the north bank of the Salsum (Guadajoz) River, a tributary of the Baetis, where there was reportedly a large supply of grain. In order to steal a march on Gnaeus, we were ordered to keep the campfires burning in order to deceive the enemy, so we left men behind in the camp to tend to them. We slipped past first Corduba, then the camp of Gnaeus, crossing over the makeshift bridge and marching through the night to arrive outside the walls of the fortress shortly before mid-day. While part of the army constructed the camp, the rest of us immediately began the contravallation of the town.