Map of a Nation (53 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

In this climate, and with the impending completion of the Irish Ordnance Survey, the continuation of the Topographical Branch could not be

justified

much longer. But it was politics that finally sounded its death knell. On 2 May 1842 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Henry Goulburn, received an anonymous letter from one who signed himself simply ‘A Protestant Conservative’. Claiming to have worked under George Petrie, this mysterious correspondent warned Goulburn in hushed tones that the Topographical Branch was composed of Irish Catholic nationalists, who formed a hothouse of sedition. The linguists’ ‘bigotry and politics are carried to all parts of the kingdom’, the writer cautioned, and ‘persons sent from this office’ had a habit of ‘taking down the pedigree of some beggar or tinker and establishing him the lineal descendant of some Irish chief, whose ancient estate they most carefully mark out by boundaries’. Here his voice rose to a hysterical crescendo: ‘They have actually in several instances, as I have seen by their letters, nominated some desperate characters as the rightful heirs to those territories.’ The scaremongering worked, and the Topographical Branch

was closed down on the basis that it was ‘stimulating national sentiment in a morbid, deplorable, and tendencious manner’.

But all was not woe: the maps themselves tell a happier story. In 1833, the first Irish Ordnance Survey maps had been published, of Derry. On 9 May of that year, its director was proud to present a six-inch map of County Londonderry to King William IV (George III’s third son, who succeeded George IV on 26 June 1830). Colby reported to his wife that the King ‘looked over the whole atlas … very carefully, sheet by sheet, asking many questions about them and the Survey, and expressing his approbation, not only of the maps, but also of his Corps of Engineers and Artillery and of the Ordnance Department under which the work was executed’. Colby was also amused that, when he had been introduced to the King, he had said that ‘“he ought to have been ashamed of himself for not immediately remembering Colonel Colby” – that he thought I had belonged to the Artillery, and did not recognise me in the Engineers’ uniform’. Maps of Antrim and Tyrone were published in 1834, and two more counties the following year. By 1842 every inch of Ireland had been mapped by the Interior Surveyors and the resulting charts were received by the public and the military with almost unalloyed pleasure. ‘No one who has seen the

six-inch

Ordnance Survey maps of Ireland, especially those of the southern counties, can fail to be struck with their great clearness and beauty,’ wrote one of Larcom’s colleagues. ‘They, for the first time, showed that by properly proportioning the relative strengths and sizes of the outline, writing and ornament, even an outline map [without hill shading] might be made a work of great artistic beauty and merit.’ A German visitor to the Ordnance Survey’s Irish headquarters noted that the maps, which had only been made by ‘common workmen’, ranked among the best in the world.

What strikes one on looking at the six-inch Irish surveys is how white and sparse they are in comparison to the one-inch maps of England and Wales, whose smaller scale brings a cluster of icons and lines together into darker and more claustrophobic sheets. The Irish maps appear more relaxed

somehow

, as if the engravers have exhaled deeply while marking the widely spaced symbols and strokes. The presence of neat field boundaries, which Mudge had commanded to be omitted from the First Series maps, gives the Irish surveys an

orderly, geometric appearance. Despite the tiny icons of shrubs and forests that nestle in the corners of walls and on the borders of beautifully rippling lakes, the Irish six-inch sheets are perhaps less evocative than their English and Welsh counterparts, whose frenzied hachures and swift transitions from hilly to flat lands inspire a breathlessness in the reader not unlike the

experience

of traversing the landscape itself.

The Ordnance Survey’s Irish maps proved far more immediately popular than their English and Welsh surveys. Thanks to Larcom’s experiments in printing methods, they were much cheaper and more accessible, the

equivalent

price of a hardback bestseller now, and salesmen touted them from door to door. The Ordnance Survey extravagantly donated full sets of the maps to almost every governmental department and major library in Ireland. Some private booksellers blew the sheets up to three or four times their intended size, and flogged them to landowners as superior estate maps (a mistake, as the magnification highlighted minuscule errors). The head of the Ordnance Survey’s Boundary Commission, Richard Griffith, reported how ‘the principal gentlemen of Ireland … all had 6-inch maps on their study walls’.

Colby was gratified to see that these Irish maps were put to many of the practical uses of which he had dreamed: the boundary survey was used to

calculate

not just the county cess tax, but poor-law rates and income taxes too. Road-builders and railway-engineers found the maps invaluable in their work, as did those involved in the draining of Ireland’s bogs. And the Geological Survey continued to base its work on the Ordnance Survey’s charts, even after that department had been detached from the Ordnance Survey and given to the Office of Works. When the last map of Ireland was published in 1846, the Ordnance Survey had finally produced a map of a nation. But it was not the nation that it had originally set out to map. The First Series of one-inch maps of England and Wales still remained unfinished.

C

HAPTER

T

WELVE

O

N

30 O

CTOBER

1841, at half past ten at night, a sentry guarding the Jewel Office at the Tower of London noticed a bright light at the windows of the Bowyer Tower, on the north side of the complex. He left his post to investigate the strange flare more closely. Transfixed at first by its shifting intensity, it was a few moments before he realised that it was a fire. Sprinting towards the Tower’s central quadrangle, the sentry started shouting with all the force he could muster. Soldiers began pouring from every doorway and the air was soon full of the sound of bugles. The Tower possessed its own fire engines, which made their way to the conflagration, where they were joined by those from neighbouring parishes, and the main gates of the complex were closed to the public. But the fire, which had begun in an overheated chimney, had already made its way to the building in front of the Bowyer Tower. The Grand Storehouse, or Armoury, was reputedly the largest room in Europe and contained some 300,000 guns, military carriages, cannon, gunpowder, bombs and various spoils of war. The soldiers who had been running towards this building quickly turned on their heels when they saw the proximity of the blaze to this informal arsenal. The next day, numerous newspapers reported how, once the fire had got hold of the Armoury, flames burst ‘from several windows with extraordinary fury’. Around midnight, the fire was reported to be ‘gushing forth from every window of the building, which had all the appearance of the crater of some volcano’. The inferno and explosions were discernible across the city, and a journalist reported how

‘the reflection on the surrounding houses, and on the shipping in the river, produced a most striking effect’.

The Map Office, which had once been situated in the White Tower, in the middle of the complex, had been moved in 1752 to the residence of the Principal Storekeeper. During the fire, this removal at first seemed fortunate. In the broadwalk that separated the Armoury from the White Tower, the heat was found to be ‘so intense, that it was utterly impossible for a human being to stand’. But soon the wind changed direction and, leaving the White Tower unscathed, the flames began to make their way west towards the Jewel Tower. Here the Crown Jewels were protected behind a locked iron grating, whose only key was in the possession of the Lord Chamberlain. With no time to hesitate, a police superintendent used a crowbar to wrench apart the iron railings and squeezed himself inside the cage. As he began passing the gems through the gap, panicked voices outside warned of the fire’s swift approach. But the superintendent continued to prise the

ornaments

from their stands, and after twenty minutes a small group of soldiers, firemen and policemen left the building unharmed, cradling a large pile of precious jewels and coronets.

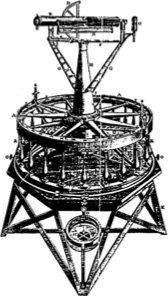

As the fire passed the Jewel Tower around two o’clock in the morning, it made its way towards the Map Office. We can imagine Thomas Colby arriving at the scene and, with the assistance of a team of soldiers, frantically packing the paper records of fifty years into boxes. Along with its

instruments

, the Ordnance Survey’s truly priceless papers and maps were quickly conveyed to safety in another part of the complex. But in the hurry and the confusion, Jesse Ramsden’s ten-foot zenith sector, which had been used for the meridian arc measurement in 1801 and 1802, and for the Shetlands extension in 1817, could not be rescued in time. When the flames finally reached the Map Office, this uniquely precise instrument was engulfed. As dawn began to appear, the headquarters of the Ordnance Survey were left in ruins.

By October 1841, most of the Ordnance Survey’s personnel had either returned to Britain from Ireland or were in the process of doing so. Colby himself had arrived back in London in 1838, and by 1842 only fifty Sappers would remain across the water. The ‘Great Fire’ at the Tower made them all

homeless. The Board of Ordnance’s officials quickly scouted around for new quarters for its map-makers, and within six days of the fire they had come up with the rather unenticing prospect of an abandoned barracks that had been used for a military school until lack of pupils had led to its closure. This building was in Southampton, about eighty miles south of the capital. Colby had spent much of his time in Ireland fantasising about his return to London, and he must have been devastated by this removal of the Board of Ordnance from the centre of government and from the grand buildings that housed many of the nation’s scientific and intellectual societies.

On 31 December 1841 the Ordnance Survey reluctantly made its move south. A member of its party recalled how ‘early in the afternoon, the first arrivals asked for admission at the entrance gates – which was refused by the old barrack-sergeant then in charge of the buildings’. But an officer called William Yolland, who had worked on the Survey for three years and was described by a colleague as ‘not a person to hold a long parley with’, soon gained admission. Over the next hours, surveying parties descended on the Southampton barracks from all over the British Isles. Inside the bare walls, there was nothing to make them comfortable and ‘everything at first was confusion’. But the following morning an Ordnance Surveyor recalled that ‘a large load of furniture, bedding, and other requisites arrived from Winchester Barracks, which was soon put in order, and by night all was

prepared

’. A team of ‘carpenters, bricklayers, smiths, masons, painters, and every kind of workman which the corps could produce were set to work’ and ‘in a very short time the establishment was got into working order’. Soon the engravers arrived too, and the Ordnance Survey’s Southampton

headquarters

were ready for business. In 1842 Colby, now fifty-eight, moved his wife and their four sons and three daughters permanently to the city, and after a visit to his comrade’s new abode, Thomas Larcom described with a hint of surprise how ‘at home, the steady calm reasoner of one moment became the next, almost the giddy boy, when playing joyously and without restraint with his children’. Over time, the Ordnance Survey took to its new residence. The mapping agency would remain at the Southampton barracks for almost a hundred years, until bombing during the Blitz devastated the site and forced the Ordnance Survey to relocate temporarily to Chessington. In 1969 a

new home was purpose-built on the outskirts of Southampton, where it is still to be found today.