Map of a Nation (47 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

many of the parishioners were greatly alarmed when the engineers first came into the country to make piles at the top of the hills for the

purpose

of triangulation. They viewed with dismay the strange-looking men erecting (as they thought) redoubts [forts] on the most

commanding

situations, and actually imagined them to be emissaries of some formidable national enemy, coming to ‘spy out the nakedness of the land’ and to mark the point from which the country below could be most easily commanded by artillery … they conceived that the

trigonometrical

station on the top of Keady was the spot from whence a fire was to be opened on the lowlands in that neighbourhood.

Other Ordnance Surveyors in Ireland were forced to place trig stations and instruments under armed guard to protect them from sabotage. Surveying poles were moved or entirely removed. Brian Friel’s 1980 play

Translations

, which dramatises the Ordnance Survey’s endeavours in

nineteenth

-century Ireland, imagines a young man from County Donegal boasting: ‘every time they’d stick one of these poles into the ground and move across the bog, I’d creep up and shift it twenty or thirty paces to the side … Then they’d come back and stare at it and look at their calculations and stare at it again and scratch their heads. And Cripes, d’you know what they ended up doing? … They took the bloody machine [the theodolite] apart!’ Some Boundary Surveyors and engineers were assaulted in Ireland, ‘perhaps from a fear that the government had invented a secret weapon’, and on Bantry Common in County Wexford the police were called out to protect a party of Interior Surveyors who were being attacked by tenants who were in conflict with their landlord. The map-makers were occasionally suspected

of being state mercenaries hired to suppress agrarian uprisings, or perhaps employees of unscrupulous estate owners. Their reputation in Ireland was not improved when one team of Ordnance Surveyors used a cairn revered by pilgrims in Tummock, in County Derry, as a trig point.

As well as out-and-out violence, hostility for the Ordnance Survey’s

presence

in Ireland was often manifested through reticence and ridicule. A map-maker charged with researching place names found the inhabitants of Dungiven to be very shy ‘in giving their [own] names because they are afraid that they might be wanted for the “service of war” or some other plan of the Government’. In Drogheda, many ‘people [were] not willing to give information, suspecting it may be connected with Tithe affairs’. In Lisburn, in County Antrim, one surveyor found that ‘some people are afraid of any one going about lest he might be a spy, and the subject of tythes is so much agitated that people are afraid of any one sent from the Government’. Elsewhere in that county, a map-maker was accosted by an angry resident who complained that ‘you have a great deal of blockheads going about annoying people’. And local residents in Connemara devised a song that, in a brief aside, mocked the map-makers’ ‘drudgery and labour’.

But not all the surveyors’ stories were full of woe. When they were not living out of tents, they brought welcome trade to inns and hostels. And in 1828 the

Dublin

Evening

Post

drew a charming picture of collaboration between the Ordnance Survey and the local populace. The journalist described how the residents of Glenomara, in County Clare, helped the Ordnance Surveyors to build a trig station. Perhaps they were motivated by simple curiosity in the endeavour, or by good relations with some of the

individual

map-makers that they had met while the latter were staying in local accommodation, or even by the hope that a cartographical image of Ireland might bolster national identity. Either way, a large crowd ascended the mountain, borne up by music from flutes, pipes and violins, and

accompanied

by young women carrying laurel leaves. However, even this contained a subversive element. The Glenomara residents insisted on naming the trig station ‘O’Connell’s Tower’, after ‘The Liberator’ Daniel O’Connell, the Irish political leader who campaigned for the repeal of the Act of Union and for Catholic Emancipation, the right of Catholics to become Members of

Parliament – an entitlement they had been denied by British penal laws from the seventeenth century.

T

HE FACT THAT

the Ordnance Survey’s Irish triangulation could be joined on to that of Britain by sight lines extending over the Irish Sea and St George’s Channel meant that measuring a baseline in Ireland was not entirely necessary. But Colby decided to do so, to make his map ‘as precise and up-to-date as

possible

’, as he put it, and to verify the Irish triangles. So on 6 September 1827 a team of surveyors began measuring a long base by the side of Lough Foyle, the estuary of the River Foyle, where it leaves Derry. Thomas Colby’s perfectionism reached new heights during the Lough Foyle measurement. He had become increasingly dissatisfied with the measuring rods and chains that had been used by the Ordnance Survey in Britain. Even the glass rods continued to respond to heat in annoying and unpredictable ways, and although microscopes had been fixed to monitor the expansion of the metals in some places, there were no means of ascertaining the susceptibility to changes in temperature of every single component of the instrument. Colby fantasised about a device that would entirely eliminate expansion and contraction due to changes in heat, so he and Thomas Drummond set about experimenting with different metals. The two men finally came up with a complex amalgamation of brass and iron bars, which were attached together at the centre but were allowed to expand or

contract

freely. When exposed to heat, the materials expanded at different rates, but they were fitted together in such a way that their different expansions cancelled one another out, leaving the total length of the instrument unchanged.

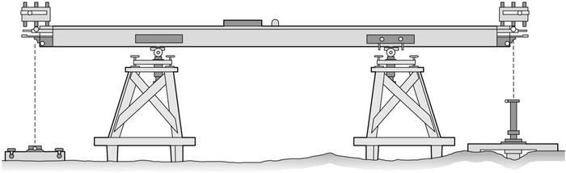

35. Colby and Drummond’s compensation bars.

The Lough Foyle baseline was measured with what became known as the ‘Compensation Bars’ in September and October 1827. After a break for the winter, the endeavour began again in July 1828. It was delayed by the

impossibility

of measuring during the harvest and was finally finished on 20 November. But the final result ‘annoyed and vexed’ Colby. ‘Where a

difference

of

inches

is scarcely admissable,’ he discovered a shocking discrepancy of ‘a

few feet

’ between the actual length and that predicted by trigonometric equations from the triangulation. Colby was perplexed, disappointed and extremely worried. He could not account for this result, which threw the veracity of the entire British and Irish Trigonometrical Surveys into question. But after a few months, the answer struck him. In 1824 a new Weights and Measures Acts had been passed by Parliament, which officially established the Imperial System in Britain. This defined a foot as twelve inches long, and a one-foot length was duly moulded in brass to act as a standard to which anyone involved in mensuration might refer. A foot had also been defined as twelve inches prior to 1824, but before that date a different brass unit had acted as the standard. The Ordnance Survey’s measurements in Britain were based on the earlier standard, and their Irish mensuration on the later one. In theory, they should have been identical, but on a comparison of the two standards, Colby found that there was indeed a minute difference, ‘not

perceptible

to the eye, or in a carpenter’s rule’, but sufficient when multiplied over long distances to knock the Ordnance Survey’s measurements off-kilter. When he adapted his calculations to account for this discrepancy, Colby found the baseline to be 41,640.8873 feet long, just under eight miles. It now accorded with the length produced by calculations from the Trigonometrical Survey to within five inches. ‘You may conceive how delighted Colonel Colby was at this result,’ the

Belfast News Letter

reported, ‘and what a triumph it is for the combined exertions of art and science.’

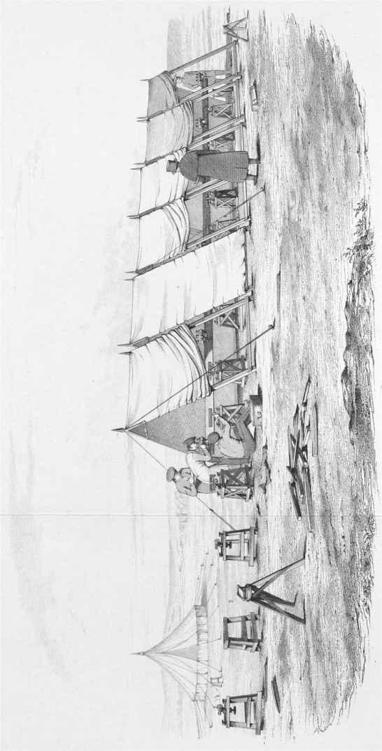

36. A sketch showing the Ordnance Survey’s measurement of the Lough Foyle baseline with the compensation bars.

The measurement of the Lough Foyle baseline, like that in Britain on Hounslow Heath, attracted many interested parties, including the British

astronomer John Herschel, the eccentric mathematician Charles Babbage and the director of the Armagh Observatory, Thomas Romney Robinson. If the surveyors sometimes felt embattled during their time mapping the Irish landscape, Colby and Larcom’s experiences at Lough Foyle reassured them that, among the Protestant scientific community at least, they were extremely welcome in Ireland. One man, a 23-year-old with brooding eyes and an intelligent brow, interrogated Colby about the Ordnance Survey’s work with particular enthusiasm and persistence.

W

ILLIAM

R

OWAN

H

AMILTON

was a wildly gifted mathematician, whose talents were sufficient to garner him the post of Andrews Professor of Astronomy at Trinity College, Dublin in June 1827, at only

twenty-one

, when he was still an undergraduate. This role also made him the Astronomer Royal of Ireland and director of the Dunsink Observatory in Castleknock, five miles north-west of Dublin. He was appointed because of his prodigious talent, but some people complained that he was not a natural choice for the job of astronomer as his passion was pure mathematics, which operated in abstraction from the material world, rather than astronomy, which was immersed in it. Even Hamilton’s friend, the poet Aubrey de Vere, said that he ‘did not look through his telescopes more than once or twice a year!’ He was ‘so much occupied with the purely abstract part of science’, de Vere explained, ‘that its material phenomena interested him only so far as they revealed laws’. Hamilton’s aptitude for pure science was exemplified when in 1832 he used laws of ‘the geometry of light’ alone, accompanied by no actual experiments, to propose that under certain circumstances a ray of light could be refracted into a cone within a biaxial crystal. Hamilton’s ‘Law of Conical Refraction’, as it became known, was subsequently proved in experiments conducted by the physicist Humphrey Lloyd. Hamilton replied to news of this proof with, ‘I told you so’, or words to that effect.