Map of a Nation (39 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

As visual images, there were often close correspondences between maps and landscape paintings. Most importantly, both could depend on geometry, which was most commonly manifested in art as perspective. Based on methods devised by the Renaissance painter Leon Battista Alberti, the encyclopaedist Ephraim Chambers defined perspective as ‘the art of delineating visible objects on a plain surface’ and the rules by which ‘the points

a, b, c

, &c. may be found geometrically’. The technique was used by many artists in history to create accurate representations of space and it often closely resembled mapping, especially the techniques of plane-tabling and triangulation. Perspective

drawings

of the landscape and these surveying methods both created geometric abstractions, and perspective was embraced by many proponents of the Enlightenment. Perspective was also central to the eighteenth-century school of neoclassical art, which rejected the flourishes of Gothic, baroque, and rococo design in favour of the purity and idealism of ancient classical models. William Mudge’s family friend Joshua Reynolds was a childhood enthusiast of

perspective

and as an adult he came to formulate a neoclassical ‘grand style’ of painting that demonstrated such ideals alongside an Enlightenment penchant for abstraction. Reynolds wanted to ‘reduce the idea of beauty to general

principles’, and his friend Edmund Burke described how Reynolds’s habit ‘of reducing every thing to one system’ derived from his ‘early acquaintance’ with Mudge’s grandfather, ‘[Zachariah] Mudge of Exeter, a very learned and thinking man, and much inclined to philosophize in the spirit of the Platonists’. In theory the Ordnance Survey therefore had much in common with

neoclassicism

, one of the most influential styles of art in the eighteenth century. Mudge and Reynolds were not only personally linked, they both loved and depended on geometry and dedicated their lives to producing abstractions of the world, in maps and paintings.

The late-eighteenth-and early-nineteenth-century movement known as Romanticism was ambivalent and sometimes downright hostile to the Enlightenment’s overriding emphasis on reason and its ambition to discover the natural world’s universal laws. It is noteworthy that many writers voiced their discontent with attacks on maps. Despite his interest in the Ordnance Survey, in his long poem

The Prelude

Wordsworth was highly critical of the ‘rational education’ that was forced on children of the Enlightenment and which idolised ‘telescopes, and crucibles, and maps’. Coleridge too felt that an upbringing that emphasised reason above all else led to the death of the imagination. Such children were ‘marked by a microscopic acuteness’, he explained. ‘But when they looked at great things, all became a blank and they saw nothing.’ Even Wordsworth’s description of the Ordnance Survey’s map-making in his Black Combe poems was ultimately ambivalent. At the end of his ‘Inscription: Written with a Slate Pencil on a Stone, on the Side of the Mountain of Black Combe’, Wordsworth imagined Mudge’s project being thwarted by a sudden ‘unthreatened, unproclaimed’ onset of thick fog, which blinded the surveyor ‘as if the golden day itself had been/ Extinguished in a moment’ – the Enlightenment’s ambitions foiled by a simple cloud.

The most outspoken attack on Enlightenment cartography in the Romantic period came from the radical poet, painter and printmaker William Blake. For Blake, the ‘

esprit géométrique

’ that defined the Enlightenment had the odious result of enslaving the human mind to reason and universal laws. Blake’s poetry and engravings prominently featured the malevolent character of Urizen, who was enchained to such rational authority, and who was

repeatedly

described with surveying instruments in his hands. Blake’s watercolour

and relief etching

The Ancient of Days

(1794) showed Urizen leaning down from the heavens and wielding a pair of dividers in threatening fashion. Blake also confronted the very hero of the British Enlightenment, Isaac Newton. Repulsed by his rational, mathematical, mechanical view of the cosmos, Blake created an image (

Newton

, 1795/

c

.1805) in which the minute idiosyncrasies of the rocks on which Newton sits resist the homogenising effect of his universal laws.

Blake also directed much of his anger about the enslavement of the

imagination

to reason onto the painter Joshua Reynolds. He annotated his edition of Reynolds’s

Discourses on Art

with savagely critical assaults. When Reynolds praised ‘truth’ and ‘geometry’, Blake wrote angrily: ‘God forbid that Truth should be Confined to Mathematical Demonstration’. He hated Reynolds’s view that the ‘disposition to abstractions, to generalizing and classification, is the great glory of the human mind’ and scribbled beside it: ‘To Generalize is to be an Idiot[.] To Particularize is the Alone [

sic

] Distinction of Merit – General Knowledges are those Knowledges that Idiots possess.’ Blake incriminated William Mudge’s family, too, in his dislike of Reynolds,

inscribing

‘Villainy’ beside a mention of ‘old [Zachariah] Mudge’ in the

Discourses

. For Blake, it seems that both men were tarred with the same brush of the tyranny of geometric reason.

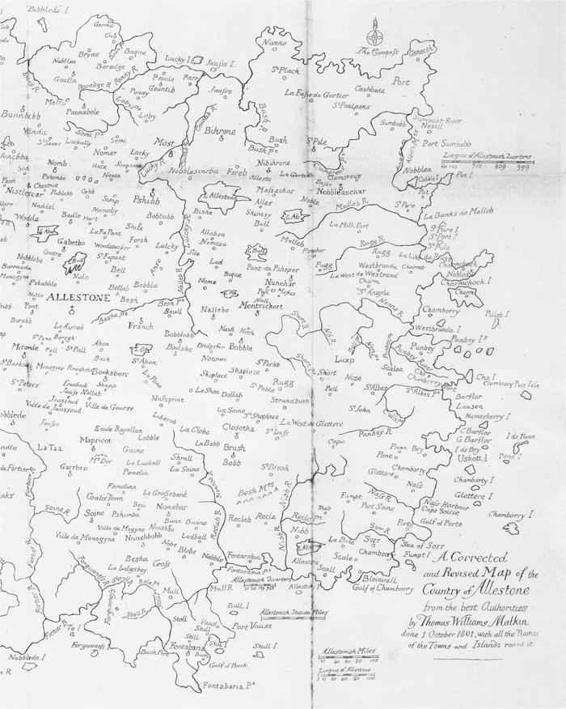

28. ‘A Corrected and Revised Map of the Country of Allestone’ by William Blake, illustrating the imaginary country of Allestone: detail.

But cartography was not entirely written off by the Romantic movement. Not at all. Many writers defended the importance of the imagination and emotions against Enlightenment reason, and some re-appropriated maps as images of these faculties. Despite his loathing for the Ordnance Survey’s type of geometric mapping, William Blake was nevertheless willing to assist when a friend called Benjamin Heath Malkin approached him to produce a map to illustrate a heart-wrenching volume of memoirs about his son Thomas’s extraordinary life and premature death. Thomas Williams Malkin had been a child prodigy, one of whose accomplishments had been to devise at the age of five an entirely ‘visionary country, called Allestone, which was so strongly impressed on his own mind, as to enable him to convey an

intelligible

and lively transcript of it in description’. Malkin had formulated an imaginary history, geography and economy for Allestone, and he had also composed a map of his fantasy kingdom, ‘giving names of his own invention to the principal mountains, rivers, cities, seaports, villages, and trading towns’.

Benjamin Heath Malkin asked Blake to engrave a map of Allestone for his

Father’s Memoirs of his Child

(1806). Blake agreed, and his resulting map was described as ‘a very remarkable production’ that was crowded ‘with names, some absurd, but others ingenious and appropriate’. His map was devoid of the type of geometry that characterised maps like the Ordnance Survey’s and it was made almost solely of minutely detailed, idiosyncratic place names. It was described as ‘

an exercise of the mind

’, a map of the imagination instead of reason.

O

NE

S

UNDAY MORNING

, on 1 August 1802, Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘Quitted [his] house’ and set off on a nine-day tour of the Lake District to seek freedom and relief in the landscape from the oppressive atmosphere of his home at Greta Hall in Keswick. He rejected the dominant modes of tourist travel: a coach or horse, and the road. Coleridge was one of Britain’s first habitual pedestrian explorers, writing exultantly in his notebook that ‘every man [is] his own path-maker – skip & jump – where rushes grew, a man may go’. Motivated variously by the expense of road travel and by Romanticism’s praise of solitude, improvisatory wandering and

independence

, combined with the desire to rebuff the status quo, by the 1790s more and more tourists could be found straying off-road, on foot, over the British landscape. Although the idea of hiking did not properly take off until the late nineteenth century, by the 1810s guidebooks routinely included advice for ramblers, and in 1824 the first footpath preservation society was formed. But when Coleridge set off on his tramp in 1802, there were serious shortcomings in the navigational aids available to him. Human guides had increasingly fallen out of fashion as the eighteenth century progressed; they were

expensive

and an obstacle to ideals of solitude. Many tourists turned to texts for navigational guidance instead, but road-books like Ogilby’s and Paterson’s trained their users’eyes only on the road ahead, and guidebooks tended to

provide

travellers with fixed itineraries around a series of principal sights. Other than advice procured from locals, there was little that was designed to allow the rambler to roam free and at will over the landscape without getting lost.

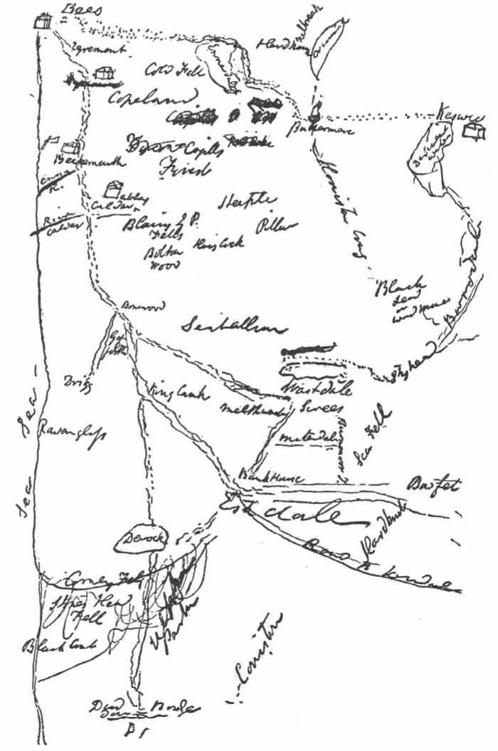

So Coleridge made himself a map. He took a small pocket-book on his hiking tour, and on the first page he drew a chart of the mountainous, craggy countryside over which he planned to wander. (This was probably copied at home from a guidebook or atlas.) Throughout his ramble, Coleridge

continued

to fill the pages of his notebook with cartographic representations and outline sketches of the western Lake District. On Thursday 5 August, Coleridge walked to Wast Water: ‘O What a Lake,’ he cried. Describing how at ‘the top of the Lake two huge Fells face each other, Scafell on right, Yeabarrow on the left – and between these Great Ga[ble] intervenes, the head & Center-point of the Vale’, Coleridge concluded that ‘it is impossible to conceive it without a Drawing’. He duly sketched a map. But Coleridge’s chart inverted reality. The enormous scree slopes that slant down, in life, to

29. A map of the western Lake District that Coleridge drew during his hike there in August 1802.

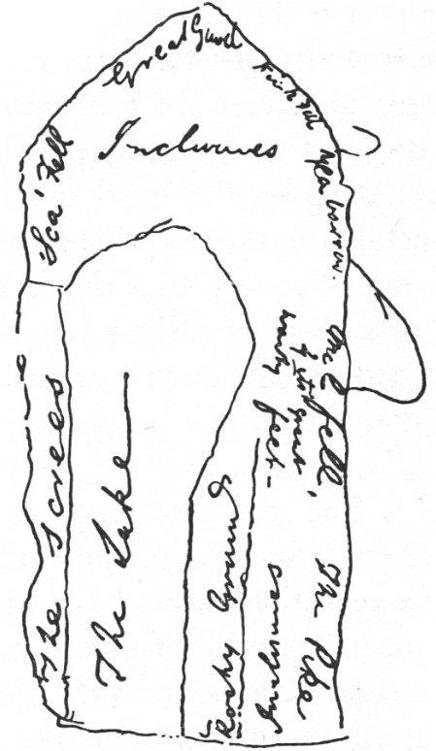

30. Coleridge’s map of Wast Water: ‘O What a Lake’.

Wast Water’s east side – ‘steep as the meal out of the Miller’s grinding Trough or Spout’, in Coleridge’s words – appeared in his map on the lake’s western bank. Every other detail was likewise turned topsy-turvy. But this mirror-image map was not just a whim or folly: it paralleled the looking-glass that Coleridge found in Wast Water itself. ‘When I first came,’ he wrote, ‘the Lake was like a mirror, & conceive what the reflections must have been … all this reflected, turned in Pillars, & a whole new-world of Images, in the water.’ His map was a personal record of one man’s imaginative experience of and response to a particular landscape, at a specific moment in time.