Manly Wade Wellman - John the Balladeer 02

Read Manly Wade Wellman - John the Balladeer 02 Online

Authors: After Dark (v1.1)

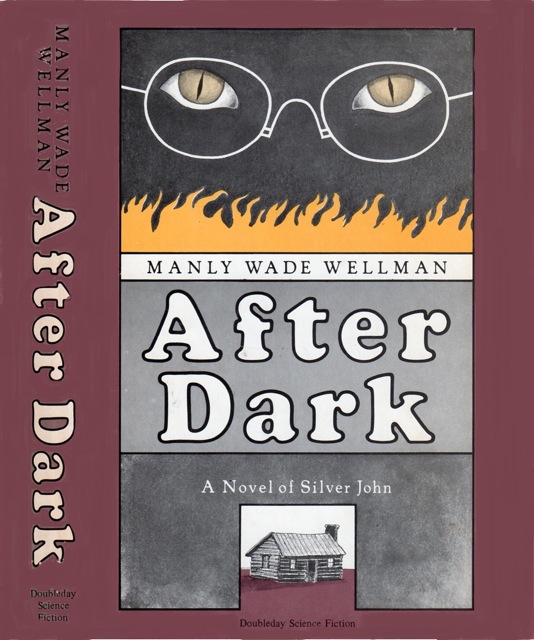

After Dark

Manly Wade

Wellman

By Manly Wade Wellman

AFTER DARK

THE OLD GODS WAKEN

After Dark

MANLY

WADE WELLMAN

DOUBLEDAY

&

COMPANY, INC.

GARDEN

CITY,

NEW YORK

1980

All of the characters in this book

are fictitious, and any resem-

blance to actual persons, living or

dead, is purely coincidental.

ISBN: 0-385-15604-9

Library of Congress Catalog Card

Number 80-650

Copyright © 1980 by Manly Wade Wellman

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the

United States of America

First

Edition

for

my

Southern mountains

and

the seers, poets, and friends I have found

among them

When

you have a memory out of darkness, tell to a seer, to a poet, and to a friend,

that which you remember: And if the

seer say

, I see

it—and if the poet say, I hear it—and if the friend say, I believe it: Then

know of a surety that your remembrance is a true remembrance.

Leabhran Mhor Gheasadiareachd (The Little

Book of the Great Enchantment)

Let

no one scorn the friendly tale,

Or

doubt, unkind, its shadowed truth. . . .

—Frank Shay, Here's Audacity

You

can feel right small and alone amongst those foresty mountains, even by the

light of the day; and the sun was a-sagging down toward a toothy sawback of

heights there at the west. I slogged my way along the track

Fd

been told was a shortcut to where the singing would be. I traveled light, as

usual. I toted a blanket with an extra shirt and socks rolled into it, a soogin

sack with a couple of tins of rations and a poke of cornmeal, and of course my

silver- strung guitar. My wide black hat had summer sweat inside the band. And

I was glad for roominess inside my old boots, resoled I can't recollect how

many times.

That

track was a sort of narrow, rutted road. It must have been run there when

wolves and buffaloes walked it, and Indians hunted after them before the first

white man was even dreamt of in those parts. Off to right and left, pointy

peaks and ridges shagged over with trees. They looked to hold memories of

witchmen and bottomless pools; of Old Devlins, who watches by a certain

lonesome river ford, though folks declare he died long years back; such things,

and the Behinder that nobody's air seen yet and lived to tell of, because it

jumps you down from behind; and a lot more, scary to think about.

Now, a cleared-off space to the left there.

I minded myself

of how I'd heard once what had fallen out there a hundred years or so back. How

Confederate soldiers had scooped up a bunch they allowed were Union

bushwhackers—maybe rightly called that, maybe not.

An unlucky

thirteen of those, a couple of them just boys a-starting their teens.

They'd sat the thirteen down, side by side on a long log, and then tore down

with their guns and killed them. Afterward, they dug a ditch right there and

buried them. No log there now, naturally, after all that long time. But folks

vow up and down that after dark the log comes back again to where once it lay.

And that those unlucky thirteen dead ones come out of their ditch and sit down

on it, maybe speak to you if you walk past in the night.

It

wasn't full night yet, as I've said; but I thought to myself, something sort of

snaky showed there, like the shadow of the log. And I made my long legs stretch

themselves longer to get away from the place, quick as I could.

Whatever

was I there to do? Well, gentlemen, I'd been a-going through the county seat,

and there were signs nailed up to tell folks about a big sing of country music,

along about sundown, the sort of thing I've always loved. It would be into the

hills near to where a settlement name of Immer had once lived and died. I’d

seen more signs about it, in

Asheville

and over the mountains in Gatlinburg and so

on. Since that was my kind of music, I'd reckoned I'd just go and hark at it

and maybe even join in with it.

“Along

about sundown'—that was all the posters had said about the time, and it would

be along about sundown right soon now. But when I rounded a bend of the track

past a bluff, I could see where I'd been headed. There was a hollow amongst the

heights, with a paved road looped into it from the far side. There stood a

ruined old building of different kinds of mountain stone, big as a courthouse,

with torn-down walls round about it. That had been an old, old hospital folks

told about; built for Immer and the other houses in the neighborhood by a

doctor—Dr. Sam Ollebeare he’d been named—who wanted to give care to the people

in those wild places. When he’d died after long years of his good work, the

hospital had gone to ruin, for no other doctor had taken over. Ruin had

likewise come, they said, to the houses where folks had lived in Immer and

round there. The folks had gone off some place else or maybe just died or just

uglied away.

Rows

of cars were parked in a big level space, and people milled round. I saw that

amongst the ruined w'alls was a big hole they used for an entrance. The folks

out of the cars walked thataway and paid their money to a man who waited for it

to be paid. A vine grew up the tumbledown wall, with white evening flowers on

it.

To

me, it seemed like as if the flowers watched

wiiile the man took in the money. I waited for the way to clear out before I

walked up to him.

"Admission

two dollars,” he said, in a sort of fadeaway voice.

I

took me a long look at him. He wasn’t big, wouldn’t have come air much higher

than my shoulder. He had a sort of tea-colored face, with a right big mane of

hair darker than mine, combed back from it His black coat came to his knees,

like a preacher’s, but it was buttoned right up to the neck. His black pants

fitted him snug and his black shoes looked to be home-cobbled. Something about

the coat and pants looked like homemade stuff too. There were big saddle

stitches at all the seams.

"Two

dollars,” he said again, like a judge in court a-telling you a fine.

"Hark

at me, sir,” I said, and smiled. "My name’s John. I pick on this guitar,

and I sort of reckoned I might

could

pick on it here

tonight, a little bit.”

He

looked me up and down, with

midnight

eyes that didn't seem like regular eyes.

Maybe he didn't much value the way I was dressed, with my old jeans pants and a

faded hickory shirt and that wide old country hat.

“John,”

he repeated me my name. “I don't believe that you've been sent for to sing

here, John.”

Just

inside that broken-down gateway hole, I saw a couple more men, a-waiting and

a-watching me. They were dressed like the gatekeeper, long black coats, with

swept- back hair. They might

could

have been brothers

to him, all brothers in a not very friendly family.

“Hold

on,” said another voice, soft but plain.

Somebody

came at us. He was middling tall, dark-haired like those others, but his hair

was cut and combed like as if it had been styled for him. He wore good store

clothes, a black and white check jacket that fitted him like a special- made

sheath for a knife, and his gray pants belled out stylish at the bottoms. On

his sharp-nosed face he had smoked glasses, though the sun was as good as down

over the heights at the west.

“Hold

on,” he said again as he came near. “What does this man want?”

“He

says he wants to sing,” mumbled the money-taking one, and he didn't sound in

favor of my a-doing that.

The

stylish fellow set his glasses on me. “Can you play that guitar with those

pretty, shiny strings?” he inquired me.

“

There's

been those who've been nice enough to say I could.”

“The

old, old songs?” was his next question. “Traditional?”

"Them,

and now and then I make me one.”

"Very

well,”

and he grinned white teeth at me. "Make

one for us to decide on. About

who

you are and what

you do.”

Another

bunch of folks was there to go in at the gate. They stood and watched while I

tuned my guitar here and there, and thought quick of some sort of tune for what

Fd

been bid to make up out of my head. I tried some

chords; something a-sounding like maybe "Rebel Soldier,” though not much:

"You

ask me what my name is,

And what I’m a-doing here—

They call me John the Wanderer

Or John the

Balladeer.

"I’ve sung at shows and

parties,

I’ve sung at them near and far,

All up and down and to and fro,

With my

silver-strung guitar.”

The

listening folks clapped me for that much, but the one with the glasses just

cocked his head, didn't nod it. "Go on,” he said, and I went on:

"Sometimes

I travel on buses,

Sometimes I travel on planes,

Sometimes I travel a-walking

On the country

roads and lanes.

"In

the homes of the rich and mighty

Sometimes I’ve laid me down,

Sometimes on the side of a mountain

On the cold and

lonesome ground.”

By

then, they all were a-listening so you could purely feel it. I stuck together a

last verse:

“I’ve

made up my songs and ballads

And sung them both far and near,

But the best of them all I’ve

whispered

With only myself

to hear.”

More

handclapping when I finished. The man with the glasses smiled again.

"Not

bad, John,” he said. "Not bad at all. Very well, come in and sing that one

for us tonight. You seem to have a ready gift.”

He

sort of stabbed his smooth-gloved hand at me, and I took it. It was nowhere the

size of my big one, but it was strong when he gripped for just a second and

then let go. "Come along,” he said, and led me inside. I made out that his

boot heels were built up to make him look taller.

They'd

set up all right for their singing. The ruins of the old stone hospital and its

outside wall closed a big space in. Logs had been strung in rows, and folks sat

on them, maybe the way those bushwhackers had sat to be shot down. They all

faced toward a stage made of poles and split puncheons, with canvas hiked up at

the back.

"My

name's Brooke Altic,” said the man, with his whitetoothed smile. "I'm

running this program. We’ll play it by ear, more or less—impromptu. Out behind

there are the other performers. Go and get acquainted, John. I'll call you to

sing your songs when it seems to be the right time.”

He

walked away, on his built-up boots.

I

went behind the stage. Some lanterns hung from the trees there, and musicians

sort of milled round. I saw instrument cases scattered here and yonder, like

shoes flung off by giants. To one side, four fellows in black shirts and pants

were softly playing together—guitar, banjo, fiddle, and bass. Nearer in, I saw

a man I knew—turkey-faced Jed Seagram with his big rodeo hat and green rodeo

shirt and the banjo he knew maybe about three honest breaks on. He was

a-talking to a girl in dark red slacks, with a fine tumble of bright yellow

hair and a guitar.

"All

I was a-saying, Miss Callie, is that you hold that guitar funny,” Jed was

a-lecturing at her.

"Well

then, listen to what I say,”

she

told him back.

"This happens to be my guitar, and I’ll happen to hold it whichever way I

choose.”

Fire

in her words, I tell you. Jed squinched his turkey face and walked off away

from her. I walked toward her.

"The

way you got Jed told was the right way,” I felt like a-saying to her.

"Wherever he is, Jed always wants to run things.”

She

looked at me with a sweet, round face, big blue eyes in it, and a mouth as red

as a cherry. "Oh,” she said, and smiled. "I know who you are; I’ve

heard you with your guitar at

Flornoy

College

. You’re John.”