Manhattan Mafia Guide (14 page)

Read Manhattan Mafia Guide Online

Authors: Eric Ferrara

December 1, 1905:

Kelly is found hiding in his cousin’s apartment at 1228 Park Avenue and is arrested in connection with the Harrington murder, though he is never convicted of a crime.

After the shooting, the headquarters at 57 Great Jones Street was ordered closed. Kelly moved to East Harlem and vowed to go straight. His Lower East Side gambling, strong-arm and prostitution rackets were divvied up among gangs led by Jack Sirocco and Chick Tricker (of the Five Points gang) and Giovanni DeSalvio (then the head of his own Jimmy Kelly gang).

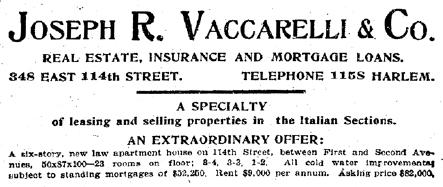

Paul Kelly successfully rebranded himself as an honest businessman, and the public bought the charade. By 1906, he was registered as a junior associate of his brother’s real estate agency, Joseph Vaccarelli & Co., at 345 East 115

th

Street, but behind the scenes, his influence was growing in labor unions. His ties to the American Federation of Labor are well documented, and Kelly became known as the go-to guy for union strong-arming and strikebreaking. In June 1907, the

Meriden Journal

reported that Paul Kelly hired fifty strikebreakers to clash with strikers of the White Star shipping line, causing numerous casualties.

Vaccarelli Real Estate advertisement, March 25, 1906.

From the

New York Times.

By the time his wife, Minnie, died at their home at 421 East 119

th

in February 1908, Kelly had been recruited to manage the Scow-Trimmers’ Union (he did not found it, as is often reported), which had about six hundred members and was headquartered at 1

st

Avenue and East 111

th

Street. Scow trimmers sorted and loaded garbage onto barges and were somewhat underrepresented until Kelly took his position and immediately initiated a strike.

On September 14, 1910, Kelly legally changed his name back to Vaccarelli. While organizing citywide strikes behind the scenes, he also engaged in several legitimate fronts, such as the Stag parking garage at 234 West Forty-first Street and a private social club called the Independent Englander Dramatic and Pleasure Club at 588 Seventh Avenue, simply referred to as “Paul Kelly’s Place” or the “Club Room.”

Being a former high-profile gangster, Kelly believed he was unfairly targeted by police and complained of several raids on his establishments, despite Kelly’s insistence that he had gone “straight.” In one case, detectives traced a car that was used in a Harlem robbery back to Kelly’s garage. It was freshly painted, but of course Kelly had no idea how it got there. Then there was the occasion when police found a roulette wheel inside the club at this address. Kelly reasonably explained that he was just holding it for a friend.

By 1912, Paul Kelly may have been itching for the spotlight he had once so easily attained as leader of the most prominent gang in New York City. On one Monday night in May of that year, he essentially held a press conference denouncing his oppression at the hands of the police department. He complained to reporters that detectives were harassing his patrons and discouraging them from entering the club. As cameras flashed, Kelly claimed he wrote a letter to the mayor complaining of these abuses, stating his innocence as a reformed gangster turned legitimate businessman. However, the police department denied targeting the social club, suggesting it was a bit of theatrics on Kelly’s part to muster some attention.

By 1915, under the name “F. Paul A. Vaccarelli,” he was made vice-president of the powerful International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA). It was here where the “former” gangster’s influence was fully realized.

Vaccarelli had an immediate and enduring effect on the shipping industry in New York and had become one of the most influential labor leaders in the city. A May 17, 1916

New York Times

headline announced, “P

AUL

K

ELLY

S

TRIKE

C

AUSES

E

MBARGO AND

T

IES

U

P

P

IERS

,” with subtitles such as “T

HUGS

T

HREATEN

W

ORKERS

” and “Employees Followed Home by Men from Longshoremen’s Union—Strike Started by Force.”

Over one thousand dock and ship workers failed to report to their posts at 6:00 a.m. on May 16 under the orders of Kelly. This bold move affected the delivery of thousands of tons of produce into the city from out west. According to reports, many longtime union members had no desire to strike but were threatened with violence by Kelly’s strong-arm men.

Longshoremen seemingly had no reason to strike at that time. They were recently awarded a modest salary increase after threatening to strike earlier in the month: thirty-five cents an hour for a ten-hour day and fifty cents for every hour after, plus a pension after twenty-five years on the job. This was considerably more than other positions earned in any industry. Paul Kelly demanded forty cents an hour, sixty cents for overtime and eighty cents for Sunday and holiday work. When demands were not met within two weeks, Kelly forced ILA members to strike. Three hundred or so who refused orders were beaten and harassed. Subsequently, the Southern Pacific steamship line, primary transporter of dried fruits and canned goods to the East Coast, declared an embargo on all shipments from its transfer stations in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Port of Galveston, Texas, which was backed up with six hundred rail cars of undelivered goods because of the strike.

Unloading banana boats in 1906.

Detroit Publishing Company (Library of Congress)

.

Southern Pacific made no bones about Paul Kelly’s ambitious shakedown. The media reported on the obvious trickledown cost that was passed on to consumers, as goods were eventually rerouted via rail. Newspapers also clearly calculated how much Kelly stood to earn from salary increases via marked-up kickbacks and “dues” from union members. Still, Kelly was somehow able to spin his image as a Robin Hood figure and retain favorable public opinion.

The strike was settled on May 21, and Kelly’s demands were met. Kelly had virtually single-handedly strong-armed a major national corporation by holding an entire industry (and city) hostage. This success only raised his profile further.

Another strike in early April 1919 threatened a “Complete Paralysis of New York Harbor,”

85

according to the

Sun

newspaper; however, an internal conflict within the ILA caused Kelly to be stripped of his vice-presidency on April 19. In true Kelly fashion, within four weeks he created a new longshoremen’s association called the Riverfront and Transport Workers Federation, announced on May 13, 1919, consisting of mostly Italian Americans who defected with Kelly from the ILA.

Shortly after losing his position in the ILA, Kelly founded the union trade newspaper called the

Loyal Labor Legion Review

. The first issue was largely dedicated to his removal from office, where Kelly claimed that twenty-two thousand members from twenty-two unions defected from the ILA to his new Riverfront Association. Kelly was actually brought back by Mayor John F. Hylan to help negotiate an end to the ILA strike later that year.

Labeled “Labor’s Lightning Change Artist” by the

New York Times

in the 1920s, over the next several years, Kelly was hired as a consultant or “business agent” to various unions throughout the tri-state area. A newspaper reported, “M

ASTER OF

M

ANY

T

RADES

. Versatile Organizer Can Load a Ship, Mix Mortar, Carry Hod, Plaster and Lay Bricks.”

86

Kelly utilized all kinds of creative methods to qualify for membership to various unions, including the time in 1923 when he learned to play the drums in order to officially join the Musical Mutual Protective Union to manage its business affairs.

In the summer of 1931, Kelly established and became president of the Loyal Labor Legion (2276 First Avenue), named after his newspaper of the same name. This “anti-union” union was considered a pioneering movement intended to “astound old line labor leaders.” The legion called for “the right of men and women to work regardless of membership or non-membership in trade unions.”

In September 1931, the legion sponsored the only celebration for workers when New York City canceled its Labor Day Parade due to high unemployment rates. This outing turned into a popular annual event at Duer’s Park in Whitestone, Queens. Though the Loyal Labor Legion gained a lot of steam and popularity, it seems to have disappeared after Kelly’s death in 1936.

According to the testimony of Joe Valachi, Kelly was doing business with the Mafia well into the 1930s, toward the very end of the gangster’s colorful and influential life.

L

ANZA

, J

OSEPH

67–69 Market Street, 1920; 102 Madison Street, 1930; 300 West Twenty-third Street, Apartment 14H, 1950s

Alias: Socks, Joe Zotz

Born: August 18, 1900, New York City

Died: October 11, 1968, New York City

Association: Genovese crime family capo

Several stints in prison did nothing to curb Lanza’s lengthy criminal career, which dates back to 1917 and lasts through the 1960s. This infamous boss of the Fulton Fish Market was described by the FBN as “one of the most accomplished terrorists in connection with labor racketeering” in the city.

Joseph Lanza mug shot, circa 1940.

Joseph’s father, Salvatore Lanza (1865–1920s), arrived in New York City from Sicily in 1895. His mother, Carmella Lofaso (September 14, 1882–?), immigrated in 1900, and the pair settled on the Lower East Side. Joseph was born soon after Carmella’s arrival; he would be the first of nine children and take on the responsibility of head of the household when his father passed away.

Fulton Fish Market, 1951. New York World-Telegram

and the

Sun

Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). Photo by F. Palumbo

.