Mandala of Sherlock Holmes (25 page)

Read Mandala of Sherlock Holmes Online

Authors: Jamyang Norbu

Tags: #Mystery, #Adventure, #Historical, #Fiction

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the Grand Lama of Hurree’s story, died on the thirteenth day of the tenth month of the Water-Bird year (17 December 1933). A year before his death he proclaimed to his subjects his last political testament and warning.

‘It may happen,’ he prophesied, ‘that here, in Tibet, religion and government will be attacked from without and within. Unless we can guard our country, it will happen that the Dalai and Panchen Lamas, the Father and the Son, and all the revered holders of the Faith, will disappear and become nameless. Monks and their monasteries will be destroyed. The rule of law will be weakened. The land and property of government officials will be seized. They themselves will be forced to serve their enemies or wander the country like beggars. All beings will be sunk in great hardship and overpowering fear; and the nights and days will drag on slowly in suffering.’

But the Great Thirteenth’s warnings were forgotten by a blinkered clergy and a weak aristocracy, who allowed his monumental works and reforms to decline and fall into disuse; so much so that the Chinese Communist Army marched into Tibet in October 1950 encountering only disorganised resistance. Then, the long endless nights began. After crushing all resistance the Chinese launched systematic campaigns to destroy the Tibetan people and their way of life. This movement reached its crescendo during the Cultural Revolution, but continues to this day, in varying degrees of violence and severity. Right now, in a deliberate policy to eradicate whatever vestige of Tibetan identity that survived previous genocidal campaigns, Beijing is flooding Tibet with Chinese immigrants; so much so that Tibetans are fast becoming a minority in their own country. In Lhasa Tibetans are an insignificant anomaly in a sea of Chinese. Even the Chinese police and military personnel, in and around the city, outnumber the Tibetan population. They are there to control and repress.

By latest estimates over six thousand monasteries, temples and historical monuments have been destroyed, along with incalculably vast quantities of priceless artistic and religious objects — and countless books and manuscripts of Tibet’s unique and ancient learning. Over a million Tibetans have been killed by execution, torture and starvation, while hundreds of thousands of others have been forced to slave in a remote and desolate gulag in North-eastern Tibet, easily the largest of its kind in the world.

The refugees who escaped this nightmare tried to re-create in exile a part of their former lives. Monasteries, schools and institutions of music, theatre, medicine, painting, metal-work, and other arts and crafts began to grow in and around Dharamsala, the Tibetan capital-in-exile, and other places in India and countries around the world where Tibetan refugees found new homes.

It was in Dharamsala, where I worked for the Education Department of the government-in-exile, that I heard, one day, of some monks from the monastery of the White Garuda (in the Valley of the Full Moon) who had escaped to India. They had even managed to set up a small community of their own in a broken down British bungalow, just outside Dharamsala town. An hour’s hard walk up the rocky mountain path brought me to the dilapidated bungalow. A few old monks were reading their scriptures, sitting cross-legged on a scraggly patch of lawn before the house. I enquired of one of them if I could talk to the person in charge.

Very soon a large but cheerful monk, who looked startiingly like the French comedian, Fernandel, came out of the house and enquired politely as to my business. I offered him the sack of fruits and vegetables that I had brought along as a gift, which was, I was happy to note, welcome to them. I was offered a rather rickety chair in their prayer-room, now empty as most of the younger monks had gone to collect firewood from the forest nearby. There was a small butter lamp burning in a make-shift altar on the mantelpiece over the old English fireplace. A calendar reproduction of the Dalai Lama’s portrait in a cheap gilded frame, was the centre-piece of this altar. Beside it stood two gimcrack plastic vases stuffed with bright scarlet rhododendron blooms that covered the mountainsides at this time of the year.

I made the customary small-talk with the stout monk, who was seated across me on a packing crate. Tea was served, made, inevitably, with CARE milk powder that tasted overpoweringly of nameless chemical preservatives. After taking a couple of mandatory sips from my cup, I got down to business.

I asked him if any of the monks remembered having a white-man, an English sahib, as the incarnate Lama of their monastery. I was really not expecting anyone to remember much, especially as it was now over ninety years since Holmes’s presence in the monastery in Tibet, and also as only very few of the older monks had managed to survive the exodus from their burning monastery to this bungalow in northern India. So it was a pleasant surprise when the big fellow replied in the affirmative.

Yes, he remembered being told of the English sahib who had been their abbot. One or two of the older monks would remember this story too, though the younger ones, the novices, would not know. I questioned him a bit more, especially about the date of Sherlock Holmes’s arrival at the monastery and the duration of his first stay there. The monk’s answers rang true each time.

‘Sir,’ said he kindly, ‘if you are so curious about our

trulku,

I can show you something that may interest you.’ He summoned a monk and sent him off to fetch something. The fellow soon returned from an interior room, bringing with him a rectangular package wrapped in old silk, which he handed over to the big monk.

My host carefully undid the silk cover to reveal a rather decrepit tin dispatch box, the sight of which caused my heart to skip a beat. He opened the case. Within it, among a few objects of religious nature, was a chipped magnifying glass, and a battered old cherry-wood pipe.

For sometime I was unable to utter a word, and when I did I am ashamed to say that in my excitement I unwittingly made a very ill-mannered and ill-considered request. ‘Could you sell me these two articles?’ I said, pointing to the lens and the pipe.

‘I’m afraid that it would not be possible,’ replied the big fellow, smiling, thankfully not offended at my gaucherie. ‘You see, these things are of great importance to our monastery. They also have some sentimental value to me.’

‘What do you mean, Sir?’ I asked puzzled.

‘Well, these are the very articles I selected as a child when they came to look for me.’

‘What!’ I exclaimed, ‘You mean …’

‘Yes,’ he replied a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. ‘You need not look so surprised.’

‘But that’s impossible!’

‘Is it really, Sir? Consider the fact carefully,’ he said in a rather didactic manner, ‘then apply this old maxim of mine: “that when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however impossible, must be the truth.”’

As I sat across from him in that dark room, lit only by a single butter lamp, he commenced to laugh softly in a peculiar noiseless fashion.

J.N.

Nalanda Cottage

Dharamsala

5 June 1989

All journeys end in the settiing of accounts: paying off porters, muleteers or camel-drivers, and rewarding the staff, especially the unfailing khansamah and, of course, the sirdar, the invaluable guide and caravan organiser. It is also the moment when one must seek adequate words of gratitude and recompense for the contributions of loyal companions, and least of all for the numerous acts of kindness and consideration one has received on the way.

First and foremost, I must acknowledge my overwhelming debt to the two greatest popular writers of Victorian England, Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling, from whose great bodies of work this small pastiche of mine has drawn life and sustenance — in much the same way as did a species of fauna mentioned in the story.

The sixty adventures of Sherlock Holmes recorded by John H. Watson are known to the followers of the ‘Master’ as the ‘Sacred Writings’. This canon of Sherlockiana, which finds parallel in the ‘Kangyur’ of Tibetan Buddhism, was the all-important source of inspiration and reference; not just for facts, but for style and even the atmosphere of my work.

The general public is pretty much unaware of the tremendous bibliography of Holmesian criticism, which is referred to generally as the ‘secondary writing’, and which finds an equivalence in the Lamaist ‘Tengyur’, or commentaries. Many such secondary sources have been consulted for this project, chief among them are Vincent Starrett’s classic,

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes,

and of course, William S. Baring-Gould,

Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street,

and also his stupendous two-volume annotated collection of the complete Sherlock Holmes stories. I should also mention two earlier attempts to reconstruct Holmes’s Tibetan period, namely Richard Wincor’s

Sherlock Holmes in Tibet,

and Hapi’s

The Adamantine Sherlock Holmes.

The first germ of an idea for the

Mandala of Sherlock Holmes

was planted in my head by the late John Ball (‘the Oxford Flyer’), the famous author

(In the Heat of the Night,

etc.), president of the Los Angeles Scion Society (of Sherlock Holmes) and a Master Copper-Beech-Smith of the sons of the Copper Beeches, of Philadelphia, who on a cold winter night at Dharamsala in 1970 examined me carefully on my knowledge of the ‘Sacred Writings’, at the conclusion of which he formally welcomed me to the ranks of the Baker Street Irregulars. (John Ball,‘The Path of the Master’,

The Baker Street Journal,

March 1971, Vol. 21 No. 1, New York.)

Kim,

Rudyard Kipling’s great novel of British India, which Nirad Choudhari considers the finest story about British India, provided a large chunk of the geographical background of the story, the ‘Great Game’ milieu, and some of its characters — the most indispensable being our Bengali Boswell to the Master. Kipling’s short stories, especially these collections:

The Phantom Rickshaw and Other Eerie Tales, Plain Tales from the Hills,

and

Under the Deodars

provided other details. I must, without fail, acknowledge the writings of Sarat Chandra Das, the great Bengali scholar/spy who is the real life inspiration for Kipling’s Hurree Chunder Mookerjee. Chief among Das’ works that animates this story is his

Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet.

I must also mention Sven Hedin’s

Trans Himalaya

which provided material for the preparation of Holmes’s kafila to Lhasa.

For background on India and the Raj: Sood’s

Guide to Simla and its Environs,

Charles Allen’s

Plain Tales from the Raj,

and also his

Raj, A Scrapbook of British India,

Geoffrey Moorhouse’s

India Britannica,

also Evelyn Battye’s

Costumes and Characters of the British Raj,

for whom I am indebted to the description of the Bombay traffic police. For esoterica: Kazi Dawa Samdup and Evans Wentz for their writings concerning ‘Phowa and Trongjug’, Andrew Tomas’s

Shambala: Oasis of Light,

and Carl Jung for the relationship of UFOs and Mandalas in the tenth volume of his collected works,

Civilisation in Transition.

Other scholars and writers whose works have either informed or inspired are acknowledged in the footnotes and quotations. Thanks to Gyamtso for the two maps and Pierre Stilli, Lindsey and especially Christopher Beauchet for their contributions to the first cover illustration. My thanks also to Esther for inputting the entire text on computer.

I am indebted to Shell and Roger Larsen for their warm and unstinted hospitality when I started writing the book and Tamsin for support. I am much indebted to friends Tashi Tsering and Lhasang Tsering for corrections, suggestions and relentless nagging to get ‘Mandala’ published; and also to Patrick French for sound advice and generous endorsement. I must thank my former editor Aradhana Bisht for helpful observations on Hurree’s character. I am particularly grateful to Ian Smith, Anthony Sheil, Elenora Tevis, Susan Schulman, Jenny Manriquez, former American ambassador to India Frank Wisner, Tenzin Sonam, Ritu Sarin, Professor Sondhi and Mrs Madhuri Santanam Sondhi for their encouragement and help to get this book published. To Amala, Regzin, and most of all Tenzing and Namkha for love and unfailing support.

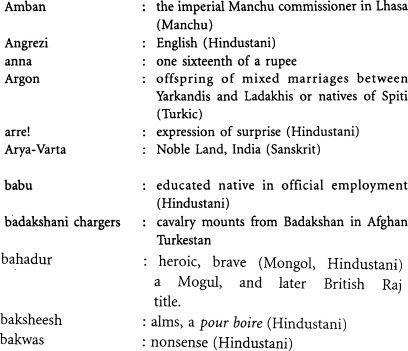

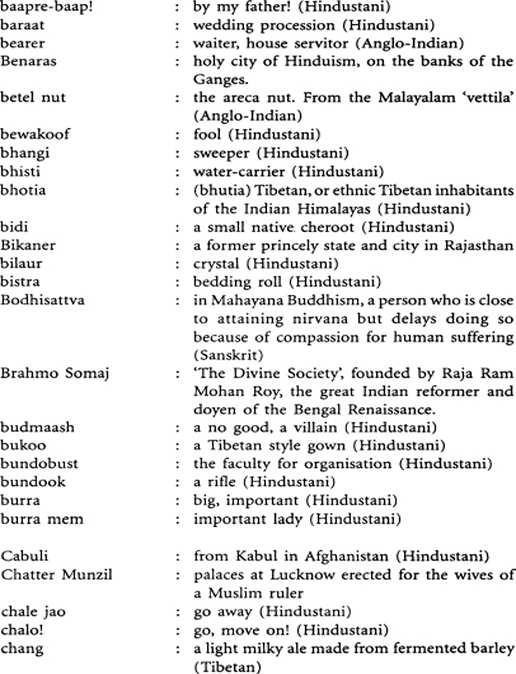

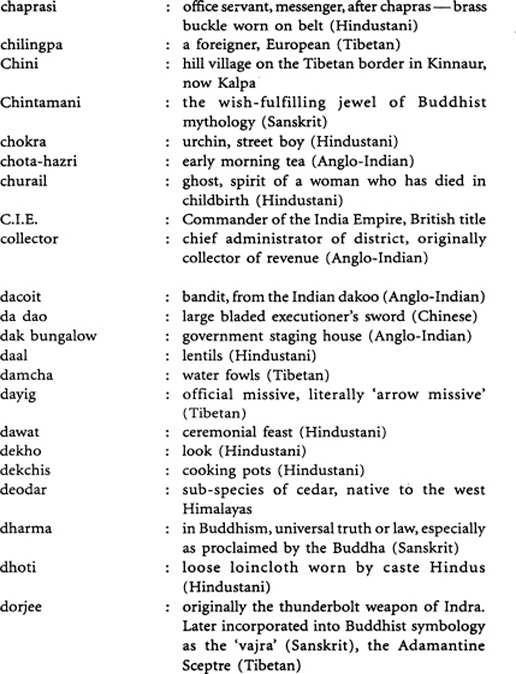

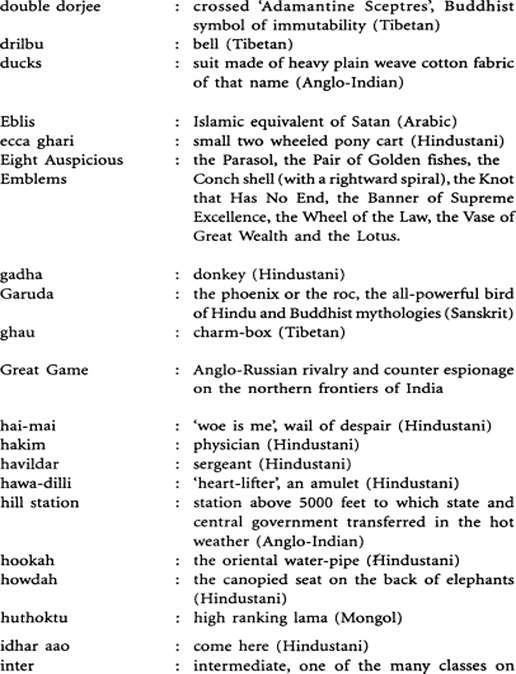

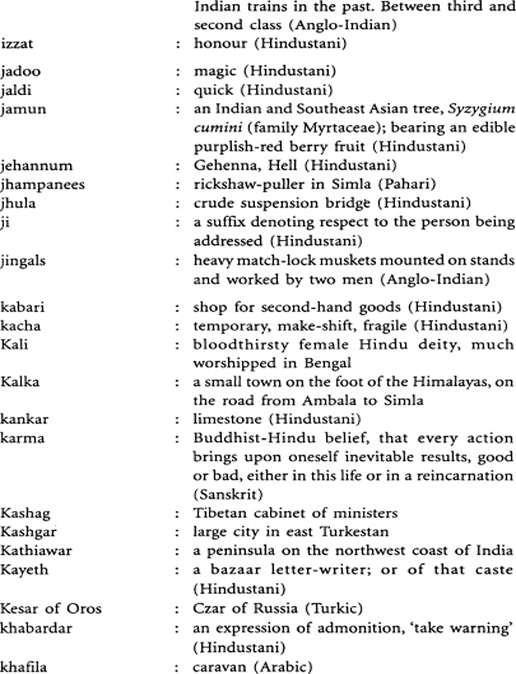

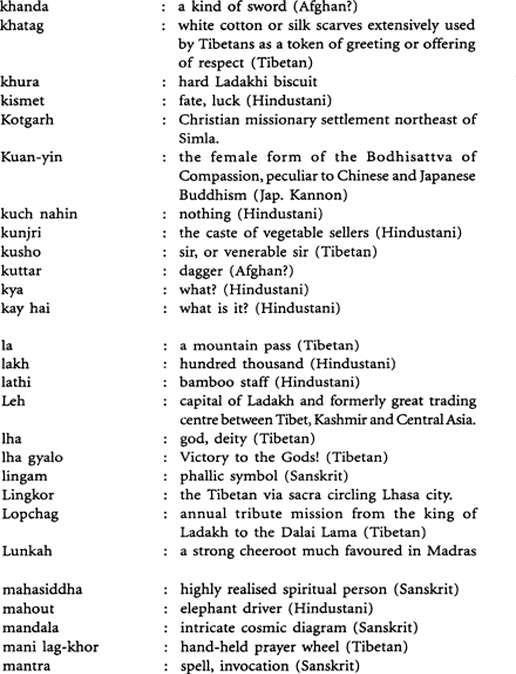

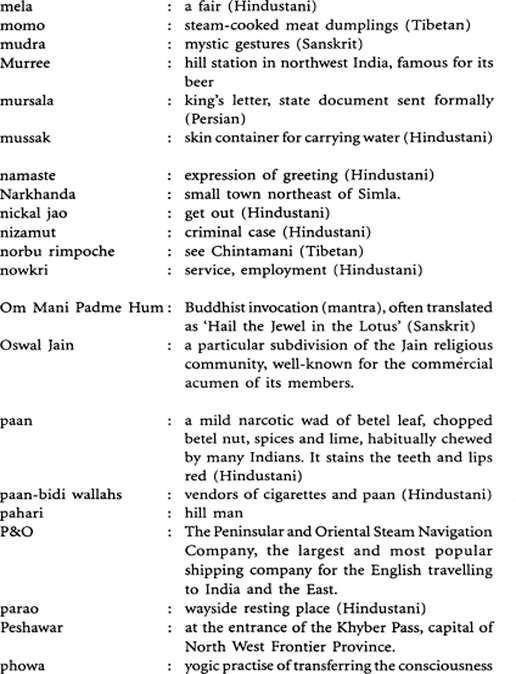

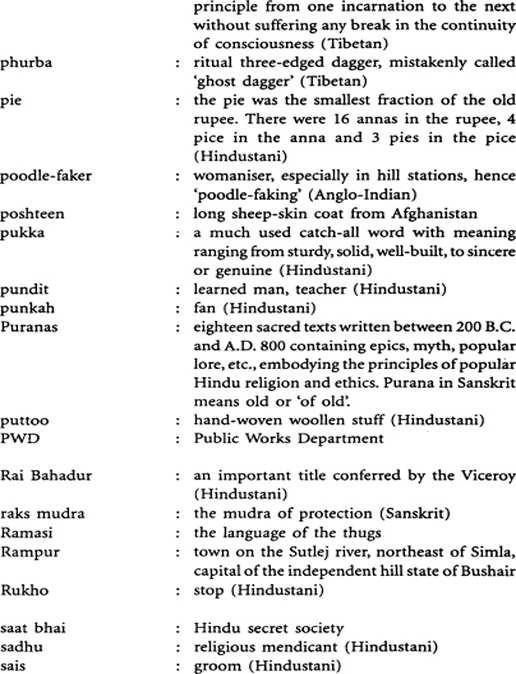

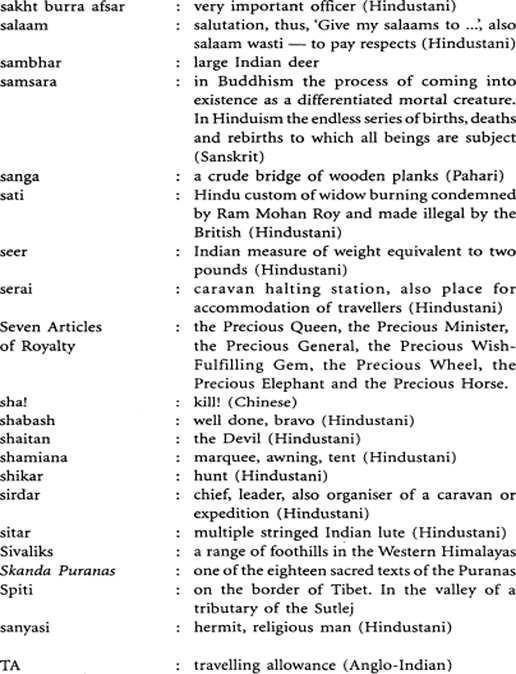

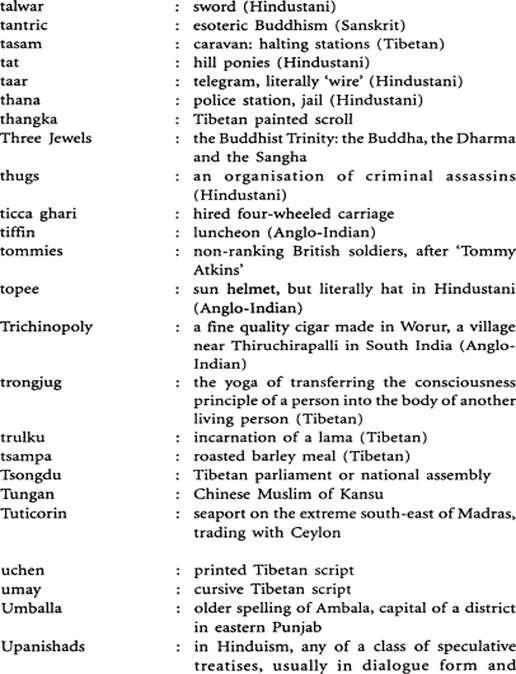

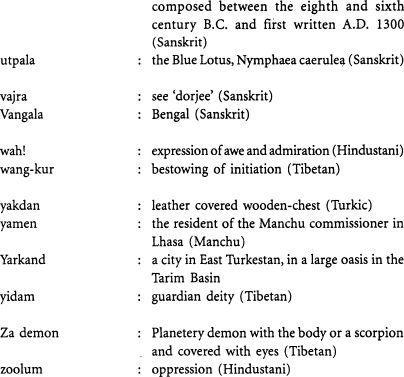

A short glossary of Hindustani, Anglo-Indian, Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese words and phrases