Man and Superman and Three Other Plays (5 page)

Read Man and Superman and Three Other Plays Online

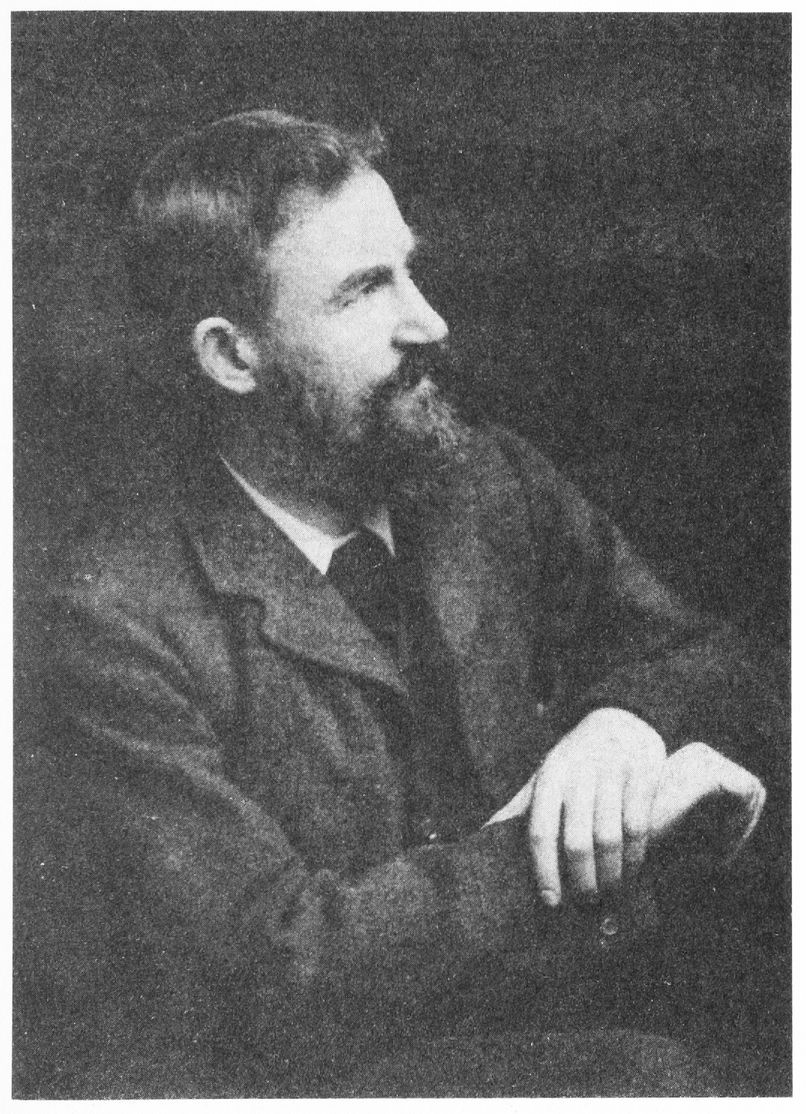

Authors: George Bernard Shaw

BOOK: Man and Superman and Three Other Plays

2.08Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

It took Shaw a year to write Man

and

Superman (1901: published, 1903; performed 1905), and well it should have, even for a man to whom, as Clive James said, writing must have been like breathing. For Shaw attempted in this big-in-every-way play to enter the arena with Dante's Divine Comedy, Milton's Paradise Lost, Shakespeare's Hamlet, and Goethe's Faust, to give an account of the cosmic purpose and destiny of the human species, and to do so through the traditional form of comedyâthat is, the story of a couple's overcoming the obstacles to their marryingâbut raised to the status of epic drama. In itself that is a comic idea. But Shaw means it seriously: He subtitled the play “A Comedy and a Philosophy.” Actually, it expounds the philosophy of comedy, which is that human beings have a justification for being alive, and that justification is striving to understand themselves so they can change into something better. The long-range means of development is evolution, but the short-range means is marriage or procreation. A man and a woman seek one another out as sexual partners, whether they realize it consciously or not, so that together they can produce a superior child. Evolutionary instincts push particular males and females together, in spite of parental, social, tribal, religious, political, or any and all artificial barriers, including personal friction between the couple, because their future child wills itself to be born healthier and smarter from them. Shaw was not a Darwinian evolutionist; he preferred Lamarck's more poetic vision of evolution, that evolution follows from a creature's will to survive and change itself in response to its environment. Shaw the optimist about human destiny found Darwin's vision of will-less adaptation too bleak because it was too mechanical. (Currently science tells us Darwin was right and Lamarck was wrong, but then Shaw's view was always more a faith than a theory, though he himself called it science.) Shaw called his own version of evolution the working of the Life Force within us, driving us to think more so that we can be more than we are now. Comedy was an ideal means for Shaw to propound his view of evolution because comedy always ridicules people for behaving mechanically, inflexibly, unyieldingly, or Darwinianly, whether in thinking or doing. Comedy defines humanity as flexibility. Only in heroic tragedy do people die for unbending principles, and receive approval for doing so.

and

Superman (1901: published, 1903; performed 1905), and well it should have, even for a man to whom, as Clive James said, writing must have been like breathing. For Shaw attempted in this big-in-every-way play to enter the arena with Dante's Divine Comedy, Milton's Paradise Lost, Shakespeare's Hamlet, and Goethe's Faust, to give an account of the cosmic purpose and destiny of the human species, and to do so through the traditional form of comedyâthat is, the story of a couple's overcoming the obstacles to their marryingâbut raised to the status of epic drama. In itself that is a comic idea. But Shaw means it seriously: He subtitled the play “A Comedy and a Philosophy.” Actually, it expounds the philosophy of comedy, which is that human beings have a justification for being alive, and that justification is striving to understand themselves so they can change into something better. The long-range means of development is evolution, but the short-range means is marriage or procreation. A man and a woman seek one another out as sexual partners, whether they realize it consciously or not, so that together they can produce a superior child. Evolutionary instincts push particular males and females together, in spite of parental, social, tribal, religious, political, or any and all artificial barriers, including personal friction between the couple, because their future child wills itself to be born healthier and smarter from them. Shaw was not a Darwinian evolutionist; he preferred Lamarck's more poetic vision of evolution, that evolution follows from a creature's will to survive and change itself in response to its environment. Shaw the optimist about human destiny found Darwin's vision of will-less adaptation too bleak because it was too mechanical. (Currently science tells us Darwin was right and Lamarck was wrong, but then Shaw's view was always more a faith than a theory, though he himself called it science.) Shaw called his own version of evolution the working of the Life Force within us, driving us to think more so that we can be more than we are now. Comedy was an ideal means for Shaw to propound his view of evolution because comedy always ridicules people for behaving mechanically, inflexibly, unyieldingly, or Darwinianly, whether in thinking or doing. Comedy defines humanity as flexibility. Only in heroic tragedy do people die for unbending principles, and receive approval for doing so.

Comedy as a genre was ideally useful to Shaw from two other angles. It allowed him to synthesize two traditions from dramatic literature: the Don Juan tradition, and the tradition of the battling couple. To take the latter first: The protagonist and antagonist of Man

and

Superman, John Tanner and Ann Whitefield, descend directly from Petruchio and Kate in The Taming

of the

Shrew and from Benedick and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. That is, before the couples finally give in to marriage, they spar and argue, insult one another, struggle against their fates, flirt with and charm one another as much as they exasperate and terrify one anotherâlike most couples. In addition, Shaw drew upon several “gay couples” (as they were called) in post-Shakespearean plays: Mirabell and Millamant in Congreve's The Way

of the

World, for example, and Sir Peter and Lady Teazle in Sheridan's The School for Scandal. Shaw borrows different elements from these couples but renovates the tradition by making the woman the avid and determined pursuer in the love chase and the man the unaware and apparently unwilling prey. Shaw cited Rosalind in Shakespeare's As You Like It as a model for his heroine as an aggressor in courtship, but he also intuited that a woman chooses a man for the kind of children he will father and for the kind of father he will be, and that goal makes her pursuit transcend the personal.

and

Superman, John Tanner and Ann Whitefield, descend directly from Petruchio and Kate in The Taming

of the

Shrew and from Benedick and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. That is, before the couples finally give in to marriage, they spar and argue, insult one another, struggle against their fates, flirt with and charm one another as much as they exasperate and terrify one anotherâlike most couples. In addition, Shaw drew upon several “gay couples” (as they were called) in post-Shakespearean plays: Mirabell and Millamant in Congreve's The Way

of the

World, for example, and Sir Peter and Lady Teazle in Sheridan's The School for Scandal. Shaw borrows different elements from these couples but renovates the tradition by making the woman the avid and determined pursuer in the love chase and the man the unaware and apparently unwilling prey. Shaw cited Rosalind in Shakespeare's As You Like It as a model for his heroine as an aggressor in courtship, but he also intuited that a woman chooses a man for the kind of children he will father and for the kind of father he will be, and that goal makes her pursuit transcend the personal.

The Don Juan tradition served Shaw well. The legend of Don Juan combines two apparently unconnected motifs. Don Juan is a man attractive to and attracted by many women whom he feels compelled to seduce. Don Juan also invites to dinner a stone Statue of an outraged father he (Don Juan) has slain in a duel, and receives in return an invitation from the Statue to dine with him in Hell. When Don Juan refuses to repent his wickedness, the Statue drags him to his damnation. The motif of the seducer anxious to spread his seed as widely as possible (insuring the survival of his genes) connects itself to the motif of damnation in that both motifs are concerned with the issue of individual mortality and immortality, with an anxiety about the future. So it is that Shaw presents us with John Tanner, an apparently antiâDon Juan, a man who believes himself not made to marry, a man who believes Ann Whitefield has designs on his best friend, Octavius, but not on himself. Yet he also does everything a male can do to impress Ann Whitefield with his qualifications for fatherhood. And in the course of the play, though he runs away from her, he comes to understand when she catches him that there is such a thing as a father's heart as well as a motherâs, and that he has one and therefore must marry Annâfor, as Benedick says when he capitulates to love, “The world must be peopled.”

In the detachable third act of the play, known, when it is performed separately, as “Don Juan in Hell,” John Tanner, having fled to the Sierra Mountains in Spain to escape Ann's pursuit and capture of him, dreams of himself as Don Juan debating with the Devil whether he (Juan) should stay in Hell or move to Heaven. Doña Ana and the Statue of her father are the audience and sometime participants in the debate. Hell, it turns out, is not unlike the world we all knowâa place where people love beauty and romance, seek pleasure, and pursue happiness, and deceive themselves about reality when it interferes with such goals. The Devil is the promoter of Hell as a paradise where the aesthetic reigns supreme. Heaven, by contrast, is the place where the Real reigns, where people work to make life more intensely self-conscious. After a seventy-five-minute discussion that is by turns witty, profound, hilarious, and dizzying about the purpose of life and the operation of the Life Force, about whether Man is primarily a creator or destroyer, about the roles of romance and sex in marriage, Don Juan finally argues himself into leaving Hell and heading for Heaven. The Statue looks upon this decision with regret since from his perspective Heaven is “the most angelically dull place in all creation.” But Doña Ana does not; she is inspired by Don Juan's decision and goes off in pursuit of “a father for the Superman.” Through his dream Tanner tells himself that by marrying Ann he will make his contribution to “helping life in its struggle upward.” Once he understands that he can marry, Shaw's new Don Juan seeks not a personal genetic immortality through the seduction of many women but the evolutionary improvement and immortality of the species by marrying one woman and becoming a father.

Shaw's plays are full of ideas, ideas of every color on the spectrum from dangerous to preposterous, from wonderful to thrilling, and, as Jacques Barzun says, it is never a question with Shaw of agreeing with all his ideas but of being moved by the vision. It is a vision that is always a play of contrary ideas, and therefore a mirror of life itselfâideas dramatized always with graceful wit, genial humor, and fearlessness, but also with the great feeling and emotional fervor that comes with thinking that life, and how it goes, and where it is headed, matter. Not for Shaw the despairing gaze into the abyssâlaughter, rather, and the imagining of hope.

JOHN A. BERTOLINI

was educated at Manhattan College and Columbia University. He teaches English and dramatic literature, Shakespeare, and film at Middlebury College, where he is Ellis Professor of the Liberal Arts. He is the author of The

Playwrighting

Self

of

Bernard Shaw and editor of

Shaw and Other Playwrights;

he has also published articles on Hitchcock, Renaissance drama, and British and American dramatists. He is writing a book on Terence Rattigan's plays.

was educated at Manhattan College and Columbia University. He teaches English and dramatic literature, Shakespeare, and film at Middlebury College, where he is Ellis Professor of the Liberal Arts. He is the author of The

Playwrighting

Self

of

Bernard Shaw and editor of

Shaw and Other Playwrights;

he has also published articles on Hitchcock, Renaissance drama, and British and American dramatists. He is writing a book on Terence Rattigan's plays.

MRS. WARREN'S PROFESSION

PREFACE

MAINLY ABOUT MYSELF

THERE IS AN OLD SAYING THAT IF A man has not fallen in love before forty, he had better not fall in love after. I long ago perceived that this rule applied to many other matters as well: for example, to the writing of plays; and I made a rough memorandum for my own guidance that unless I could produce at least half a dozen plays before I was forty, I had better let playwriting alone. It was not so easy to comply with this provision as might be supposed. Not that I lacked the dramatist's gift. As far as that is concerned, I have encountered no limit but my own laziness to my power of conjuring up imaginary people in imaginary places, and making up stories about them in the natural scenic form which has given rise to that curious human institution, the theatre. But in order to obtain a livelihood by my gift, I must have conjured so as to interest not only my own imagination, but that of at least some seventy or a hundred thousand contemporary London playgoers. To fulfil this condition was hopelessly out of my power. I had no taste for what is called popular art, no respect for popular morality, no belief in popular religion, no admiration for popular heroics. As an Irishman I could pretend to patriotism neither for the country I had abandoned nor the country that had ruined it. As a humane person I detested violence and slaughter, whether in war, sport, or the butcher's yard. I was a Socialist, detesting our anarchical scramble for money, and believing in equality as the only possible permanent basis of social organization, discipline, subordination, good manners, and selection of fit persons for high functions. Fashionable life, though open on very specially indulgent terms to unencumbered “brilliant” persons (“brilliancy” was my speciality), I could not endure, even if I had not feared the demoralizing effect of its wicked wastefulness, its impenitent robbery of the poor, and its vulgarity on a character which required looking after as much as my own. I was neither a sceptic nor a cynic in these matters: I simply understood life differently from the average respectable man; and as I certainly enjoyed myself moreâmostly in ways which would have made him unbearably miserableâI was not splenetic over our variance.

Judge then, how impossible it was for me to write fiction that should delight the public. In my nonage I had tried to obtain a foothold in literature by writing novels, and did actually produce five long works in that form without getting further than an encouraging compliment or two from the most dignified of the London and American publishers, who unanimously declined to venture their capital upon me. Now it is clear that a novel cannot be too bad to be worth publishing, provided it is a novel at all, and not merely an ineptitude. It certainly is possible for a novel to be too good to be worth publishing; but I pledge my credit as a critic that this was not the case with mine. I might have explained the matter by saying with Whately,

a

“These silly people don't know their own silly business”; and indeed, when these novels of mine did subsequently blunder into type to fill up gaps in Socialist magazines financed by generous friends, one or two specimens took shallow root like weeds, and trip me up from time to time to this day. But I was convinced that the publishers' view was commercially sound by getting just then a clue to my real condition from a friend of mine, a physician who had devoted himself specially to ophthalmic surgery. He tested my eyesight one evening, and informed me that it was quite uninteresting to him because it was “normal.” I naturally took this to mean that it was like everybody else's; but he rejected this construction as paradoxical, and hastened to explain to me that I was an exceptional and highly fortunate person optically, “normal” sight conferring the power of seeing things accurately, and being enjoyed by only about ten per cent of the population, the remaining ninety per cent being abnormal. I immediately perceived the explanation of my want of success in fiction. My mind's eye, like my bodyâs, was “normal”: it saw things differently from other people's eyes, and saw them better.

a

“These silly people don't know their own silly business”; and indeed, when these novels of mine did subsequently blunder into type to fill up gaps in Socialist magazines financed by generous friends, one or two specimens took shallow root like weeds, and trip me up from time to time to this day. But I was convinced that the publishers' view was commercially sound by getting just then a clue to my real condition from a friend of mine, a physician who had devoted himself specially to ophthalmic surgery. He tested my eyesight one evening, and informed me that it was quite uninteresting to him because it was “normal.” I naturally took this to mean that it was like everybody else's; but he rejected this construction as paradoxical, and hastened to explain to me that I was an exceptional and highly fortunate person optically, “normal” sight conferring the power of seeing things accurately, and being enjoyed by only about ten per cent of the population, the remaining ninety per cent being abnormal. I immediately perceived the explanation of my want of success in fiction. My mind's eye, like my bodyâs, was “normal”: it saw things differently from other people's eyes, and saw them better.

This revelation produced a considerable effect on me. At first it struck me that I might live by selling my works to the ten per cent who were like myself; but a moment's reflection showed me that these would all be as penniless as myself, and that we could not live by, so to speak, taking in one another's washing. How to earn my bread by my pen was then the problem. Had I been a practical commonsense moneyloving Englishman, the matter would have been easy enough: I should have put on a pair of abnormal spectacles and aberred my vision to the liking of the ninety per cent of potential bookbuyers. But I was so prodigiously self-satisfied with my superiority, so flattered by my abnormal normality, that the resource of hypocrisy never occurred to me. Better see rightly on a pound a week than squint on a million. The question was, how to get the pound a week. The matter, once I gave up writing novels, was not so very difficult. Every despot must have one disloyal subject to keep him sane. Even Louis the Eleventh had to tolerate his confessor, standing for the eternal against the temporal throne. Democracy has now handed the sceptre of the despot to the sovereign people; but they, too, must have their confessor, whom they call Critic. Criticism is not only medicinally salutary: it has positive popular attractions in its cruelty, its gladiatorship, and the gratification its attacks on the great give to envy, and its praises to enthusiasm. It may say things which many would like to say, but dare not, and indeed for want of skill could not even if they durst. Its iconoclasms, seditions, and blasphemies, if well turned, tickle those whom they shock; so that the critic adds the privileges of the court jester to those of the confessor. Garrick, had he called Dr. Johnson Punch, would have spoken profoundly and wittily, whereas Dr. Johnson, in hurling that epithet at him, was but picking up the cheapest sneer an actor is subject to.

Other books

The Man Who Would Be F. Scott Fitzgerald by David Handler

Los cuclillos de Midwich by John Wyndham

All Unquiet Things by Anna Jarzab

Diamonds Forever by Justine Elyot

Vile Blood by Max Wilde

Interlocking Hearts by Roxy Mews

Bloodrage by Helen Harper

No Cure for Murder by Lawrence Gold

Drawing Conclusions by Deirdre Verne

The Last Talisman by Licia Troisi