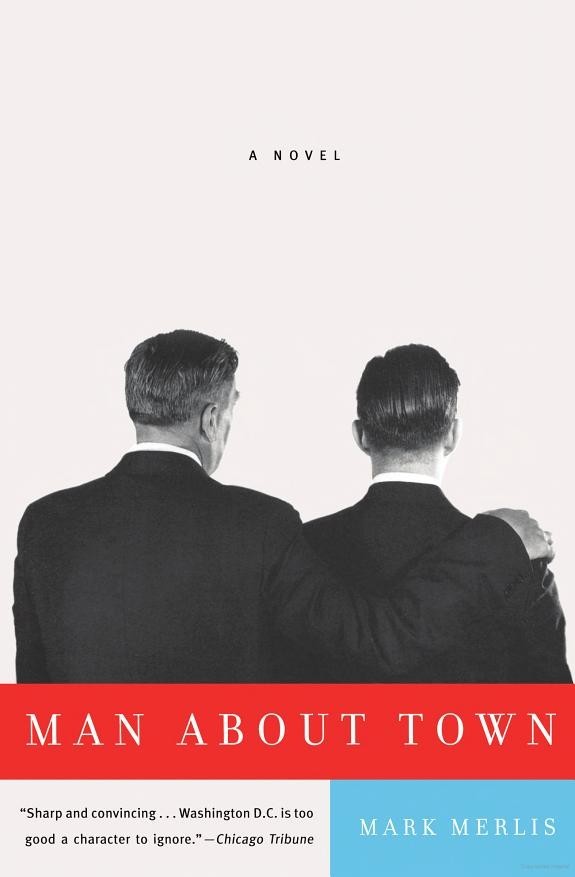

Man About Town: A Novel

man

about

town

a novel

Mark Merlis

For Leslie Breed and always for Bob

It was almost six o’clock, so Joel Lingeman wanted a drink.

Senator Flanagan did, too, probably. He looked attentive enough. He had his head tilted more or less in the direction of Senator Harris, who was trying to explain something about Medicare hospital payments. Only the solitary, pudgy finger beating rhythmically on the arm of his chair betrayed that Flanagan’s thoughts were the same as Joel’s: they weren’t going to finish that evening, there were about fifty more amendments, and the big ones late on the list. The Republic would not be imperiled if the Finance Committee recessed until tomorrow and everybody went off and had a drink.

Joel could almost hear Flanagan say it, the way he used to when he was chairman. “Let us recess until the morrow.” How Flanagan used to love to say “the morrow,” relishing and at the same time mocking its formality, drawing out the last syllable into a round mantra of transcendental self-esteem. Except he wasn’t the chairman any more; a Republican was

the chairman. So Flanagan didn’t get to say when the committee would recess, no more than Joel did.

Flanagan gazed out at the room now, over half-moon glasses that somehow clung to the very tip of his prodigious whiskey nose. He scanned the little audience of staffers and Administration satraps gathered for the hearing, and his eyes met Joel’s. Joel had worked on the Hill twenty years, Flanagan must have seen him a thousand times, but of course a senator wouldn’t recognize Joel. Still, for a moment there passed between them a look such as might have been exchanged by the Sun King and a serving boy, each in his way held captive at some interminable dinner.

The committee had been marking up the chairman’s Medicare proposals since about three—that was the phrase,

marking up,

as if each senator had come with his own little blue pencil. Three hours already, if you didn’t count the long breaks when senators left for a floor vote, three hours of deliberation on gripping subjects like clinical laboratory reimbursement. Even a senator, whose entire job was just to keep his eyes open at sessions like this one, might have been forgiven if he had once or twice nodded off. But Flanagan dutifully turned back to Senator Harris, one eyebrow raised, his thin bluish lips curled in the little Buddha smile he always wore as he listened indulgently to a jerk.

Senator Harris was still expatiating about hospital payments in Montana. Joe Harris—that was how senators styled themselves now, Joe or Dick or Bob—had to be the most vacuous whore in the Senate. No one had ever heard a sensible word from him, nor detected a principle he would not abandon for a three-course lunch, unless making sure he never had a hair out of place was a principle. But he was kind of cute.

Joel had been noticing lately that there were a couple of cute senators. This was a function of his own aging, of course: when he had started in this job, all the senators were old men. Majestic, distant figures named Everett or Hubert who strode

through the corridors talking gravely about matters of state. Some time when Joel wasn’t looking, there had arrived these brisk, trim, thirty-something nonentities, each with his little White House dream.

Whereas Joel was forty-five and had arrived at his terminal placement. This didn’t bother him especially; he didn’t mind being forty-five, he didn’t mind his placement. But it was eerie, sitting in a committee room in the Dirksen Senate Office Building and watching these juveniles acting like senators, as if they were in a high-school play. Joel’s generation had taken over the world. The generation after Joel’s really—in the person of moderately cute Joe Harris.

Harris looked even younger than most, with the faintly deranged perkiness of a Dan Quayle or a John Kasich. It was hard for him to look grown-up and serious as he presented some amendment he didn’t understand to help some constituents he didn’t care about. He was just finishing his prepared remarks about it, and he had the relieved look of a school kid who has delivered his book report without throwing up.

Senator Altaian had a question. Senator Altaian always came up with a question, just to show off, as if he were still the valedictorian at the High School of Science. Flanagan turned with histrionic ponderousness and looked at Altaian with frustration and contempt—somehow conveying all this without breaking his smile. Nobody cared about the amendment, the chairman had already okayed it, it affected about three goddamn hospitals in Montana. They didn’t have to take half an hour on it just so Altaian could display his earnestness and intellect. Of course, Flanagan used to spend whole afternoons in similar self-display back when he was in charge. But he never ran over into the cocktail hour.

Harris couldn’t answer the question. He raised his hand over his right shoulder, serenely confident that his legislative aide would already be hovering behind him with the relevant piece of paper. The LA, a tiny, harried-looking woman, was there.

Harris took the paper without looking at her or thanking her. They said he sometimes threw things at his aides. Papers, books, once a telephone. This primordial management technique evidently worked: the LA not only had the precise piece of paper he needed, but had a copy all ready for Altman.

Harris’s paper was some sort of spreadsheet; Altman and Harris slogged through it together, column by column. They were, respectively, the junior Democrat and junior Republican on Finance, so they faced each other from the two extremities of the horseshoe-shaped committee desk at whose apex were the chairman and Flanagan.

Harris couldn’t figure out what the different columns in his spreadsheet were. Altman peppered him with questions, and he was too proud to turn to his LA, who was literally kneeling behind him, for the answers. He stammered, got more and more confused, turned red with embarrassment and anger; this would be a phone-throwing night.

Flanagan stood up, exasperated, and darted out through the little door behind the dais. Headed for his hideaway, probably, and a shot or two of Irish whiskey. Senators could leave the room when they felt like it; Joel couldn’t.

No, that wasn’t right. Joel was a free adult, as free as Flanagan. He could have left if he’d wanted to, he wasn’t strapped to his chair. Probably no one would have missed him if he had got up, like Flanagan, and had run off to his own hideaway—the Hill Club, just a few blocks away—for a quick one. Except then this would be the night, wouldn’t it, when someone would have a question only he could answer. “What the hell happened to Lingeman? He was right here …”

What then? They wouldn’t fire him. There were people in the Office of Legislative Analysis who had no apparent vital signs and who got merit increases every year. They wouldn’t fire Joel Lingeman if he happened to disappear for twenty minutes, or thirty, tops, just a quick one and a couple of cigarettes. This anarchic thought scared him. It was so easy to

move on to the next thought: go to the Hill Club and don’t come back at all. And the next: don’t show up for work at the OLA tomorrow morning. And the last, terrifying—leave it all. Job, apartment, even his lover Sam: ditch it all. Go somewhere and live on his 401(k) and … But there were penalties for drawing on your 401(k) when you were only forty-five. There were penalties for everything.

Joel slouched down in his seat and stared up at the ceiling. For some reason the ceiling in the Finance Committee room had plaster bas-reliefs of the signs of the zodiac. Whose whimsy had this been, to adorn a chamber in the Dirksen building with goats and crabs?

Harris’s LA suddenly materialized to Joel’s left, whispered urgently, “I can never figure out this payment stuff. What on earth is a ‘Medicare-dependent hospital’?”

“Um,” he said. A good thing he hadn’t left. What was her name? Melanie something. Wearing an ill-chosen red suit with frogs of black braid, such as an organ grinder might have picked for his monkey. Practically a schoolgirl, like all the LAs. “It’s, like, a little hospital that no one will go to if they can drive anywhere else. So all they get is old people on Medicare.”

“Oh,” Melanie said. “Are there a lot of those in Montana?”

“Beats me. Don’t you know?”

“I’ve never even been there. I just started with the senator a few months ago.”

“Right, I remember.” They came and went so quickly, LAs: a year or two on the Hill, then off to be a lobbyist for a pharmaceutical company. This was just as well. If any of them had stayed long enough to learn their jobs they wouldn’t have needed Joel, would they? “Anyway, these hospitals live on their Medicare money, so there are these special payment rules for them. First of all—”

Melanie shook her head; this was already too deep. “You’d better come up and explain to the senator.”

Joel was startled: this happened once in a blue moon. Staffers

hardly ever wanted him to talk to their members. Because of course they didn’t want to admit that there were questions they couldn’t answer.

Melanie led the way to the dais. Joel followed her without much trepidation. Senators were a little scarier than congressmen, even more prone to look at you as if you were some sort of lizard who had chanced to enter their field of vision. Still, all you had to do was remember that the instant you were out of sight they would forget they had ever encountered you. Forget that along with whatever bit of information you had tried to impart.

Joel and Melanie crouched behind Harris’s seat and Joel—whispering and using very small words—explained the obscure payment rule Harris was proposing to amend. Harris sucked his lips in and tried to look comprehending. Joel was short of breath for some reason, maybe just thrilled with his own momentary importance. But he went on until Harris nodded and put a hand up. Meaning either that he understood or that he wasn’t ever going to; either way, he’d heard enough.

Harris squinted at Melanie. “If you drafted this, why can’t you explain it?”

“I didn’t draft it. The state hospital association people gave it to you at that breakfast last week.” Along with a check, probably.

“Oh, right.” He turned back to Joel. “So, does this cost anything?”

“It’s an asterisk,” Joel said. Meaning a cost that rounded to less than a million.

“Fine.” Harris smiled, actually thanked Joel, before turning to the microphone and playing back everything Joel had just told him. With surprising accuracy, but as if he had learned the words phonetically, like a foreign starlet making her Hollywood debut.

Altman, his tormentor, retreated. “Okay, I get it,” he said.

Abruptly, because of course he didn’t understand Medicare hospital payments any better than Harris. This had all taken a good fifteen minutes, for a lousy asterisk. The time they spent on things seemed to be in inverse proportion to their importance; billion-dollar items flew right by. Maybe this could all be expressed as some sort of equation. Where

t

is time and

m

is money,

t = 1/m

n

. If he could just have figured out the formula, Joel might have computed exactly how long it would be before he could have a drink.

He was still feeling, as he headed back to his seat, that strange breathlessness. Not nerves, something almost sexual—as if a bubble of elation had arisen from somewhere and stuck in his throat.

Once in his seat he closed his eyes for a second and tried to imagine going to bed with Joe Harris. That is, he didn’t spontaneously imagine it, he made himself imagine it as a sort of diagnostic test, to find the sore spot in him. Harris was undoubtedly straight, must have had the standard-issue buck-toothed wife and photogenic kids. So they didn’t go to bed, exactly; Harris just unzipped his fly and brought forth his penis, the Member’s member, for Joel to suck.