Malinche

Authors: Laura Esquivel

Praise for

New York Times

bestselling author Laura Esquivel's poignant, enthralling tale

MALINCHE

“Lyrical.”

â

The New York Times

“Esquivel's writing is always ambitious and inventive.”

â

Los Angeles Times

“A vividly imagined portrait of Malinche.”

â

San Antonio Express-News

“Elegant and simple prose.”

â

New York Post

“Fascinating and well-written.”

â

Library Journal

“A lush foray into the world of one of Mexican history's most controversial figures.”

â

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“Laura Esquivel, a celebrated Mexican author, defies traditional mythology and gives us a legendary historical love story.”

â

Cosmopolitan en español

“A remarkable story.”

â

Latina

magazine

“An enchanting, imaginative account.”

â

Spirituality & Health

magazine

“Malinalli is a prism through which we can also glimpse what it is about Laura Esquivel's sensibility that has made her a bestselling novelist.”

â

Hispanic Magazine

Washington Square Press

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2006 by Laura Esquivel

English translation © 2006 by Laura Esquivel

Illustrations © 2006 by Jordi Castells

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

www.SimonandSchuster.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Atria hardcover edition as follows: Esquivel, Laura, date.

Malinche: a novel / Laura Esquivel; translated by Ernesto

Mestre-Reed; illustrated by Jordi Castells.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Marina, ca. 1505-ca. 1530âFiction. 2. Cortés, Hernán, 1484-1547âFiction. 3. Mexico-HistoryâConquest, 1519-1540âFiction. I. Title.

PQ7298.15.S638M35 2006

863'.64âdc22

2005057124

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-9991-6

ISBN-10:Â Â Â 0-7432-9991-4

First Washington Square Press trade paperback edition April 2007

WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discount for bulk purchases, please contact Simon and Schuster Special Sales at 1-800-456-6798 or [email protected].

To the Wind

T

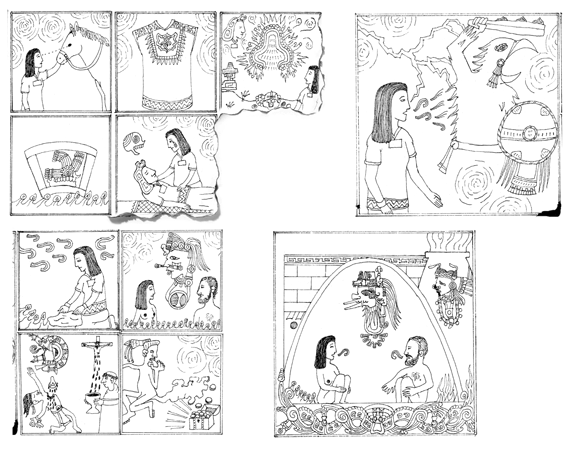

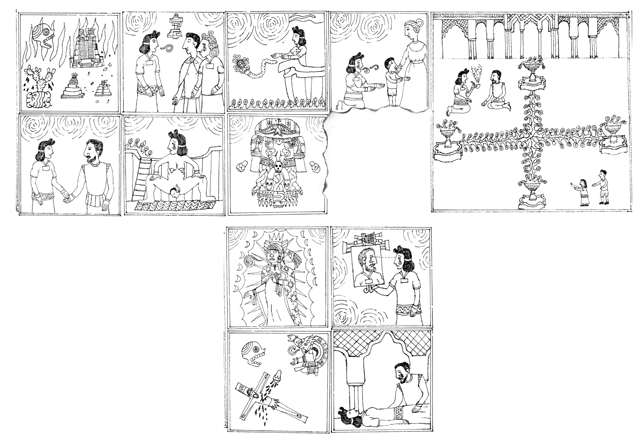

o enter what wasâor what may have beenâthe world of Malinche, proved to be a fascinating experience: to imagine the stars she gazed at, what her favorite flowers were, what food she liked best, what it meant in her daily life to light a fire, what gods she turned to in times of anguish. And I soon realized that the image she probably had in her mind of any god, would have come from a codex or a sculpture.

The history of the civilizations that inhabited the American continent before the arrival of the Europeans, the memory of the tribe, was preserved either by oral tradition or through images, not through written language. The ancient Mexicas told the epic poems of their people through images. All their experiences were recorded on pieces of paper that represented a way of existing in time. Those documents were called codices and their creation was so important, as much in the artistic conception of them as in the material realization, that the “writers” of codices were considered superior beings and their activities sacred. In fact, they were exempted from paying taxes to the state, so fundamental was their work considered in the culture of pre-Hispanic America.

The codices preserved all the knowledge of the pre-Columbian civilizations. From those that were spared destruction, we can come to know the images of the gods or the history of the emperors, their forms of tribute and of healing, all the way up to the most heartrending chronicles dealing with the arrival of the Spaniards, with the falls of empires and the process of conquest. The codex was a sacred mode with which to tell stories, profane and holy stories. And so the codex symbolizes a process of mediation, it unifies the mental effort to explain events rationally with the artistic and religious experience of expressing the world emotionally and spiritually through concrete images full of color and whimsical shapes.

Some historians have asserted that the most important image for cultural reconciliation of the Spanish conquest of American lands is that of the Virgin of Guadalupe. She has been conceived and imagined as one of the most sophisticated forms of the codex. In each of the brushstrokes of “The Dark Lady of Tepeyac” there exist coded languages that were understandable only to the Mexica people, though in no way could you ignore the interpretations that were addressed to the Spaniards, the criollos, and the race of mestizos that we now justly call Mexicans.

For these reasons, I thought it essential that this novel be accompanied by a codex, the codex that Malinche might have painted. The codex would represent what the words narrate in another fashion. In this manner I try to conciliate two visions, two ways of storytellingâthe written and the symbolicâtwo breaths, two yearnings, two times, two hearts, in one.

Malinche