Make A Scene (4 page)

Authors: Jordan Rosenfeld

Georgette stretched lazily on the balcony. An ambulance wailed below. A

man with a shopping cart stood underneath my apartment building, eating

chicken wings and whistling.

If the entire scene had continued in narrative summary, it most certainly would have had a sedative effect on the reader, and the scene's momentum would have been lost.

Narrative launches should be reserved for the following occasions:

•When narrative summary can save time.

Sometimes actions will simply take up more time and space in the scene than you would like. A scene beginning needs to move fairly quickly, and on occasion, summary will get the reader there faster.

•When information needs to be communicated before an action.

Sometimes information needs to be imparted simply in order to set action in motion later in the scene. Consider the following sentences, which could easily lead to actions: "My mother was dead before I arrived." "The war had begun." "The storm left half of the city under water."

• When a character's thoughts or intentions cannot be revealed in action.

Coma victims, elderly characters, small children, and other characters sometimes cannot speak or act for physical, mental, or emotional reasons; therefore the scene may need to launch with narration to let the reader know what they think and feel.

SETTING LAUNCHES

Sometimes setting details—like a jungle on fire, or moonlight sparkling on a lake—are so important to plot or character development that visual setting must be included at the launch of a scene. This is often the case in books set in unusual, exotic, or challenging locations such as snowy Himalayan mountains, lush islands, or brutal desert climes. If the setting is going to bear dramatically on the characters and the plot, then there is every reason to launch with it.

John Fowles's novel

The Magus

is set mostly on a Greek island that leaves an indelible imprint on the main character, Nicholas. He becomes involved with an eccentric man whose isolated villa in the Greek countryside becomes the stage upon which the major drama of the novel unfolds. Therefore, it makes sense for him to launch a scene in this manner:

It was a Sunday in late May, blue as a bird's wing. I climbed up the goat-paths to the island's ridge-back, from where the green froth of the pine-tops rolled two miles across to the shadowy wall of mountains on the mainland to the west, a wall that reverberated away south, fifty or sixty miles to the horizon, under the vast bell of the empyrean. It was an azure world, stupendously pure, and always when I stood on the central ridge of the island, and saw it before me, I forgot most of my troubles.

The reader needs to be able to see in detail the empty Greek countryside in which Nicholas becomes so isolated. It sets the scene for something beautiful and strange to happen, and Fowles does not disappoint. To create an effective scenic launch:

• Use specific visual details.

If your character is deserted on an island, the reader needs to know the lay of the land. Any fruit trees in sight? What color sand? Are there rocks, shelter, or wild, roaming beasts?

•Allow scenery to set the tone of the scene.

Say your scene opens in a jungle where your character is going to face danger; you can describe the scenery in language that conveys darkness, fear, and mystery.

•Use scenery to reflect a character's feelings.

Say you have a sad character walking through a residential neighborhood. The descriptions of the homes can reflect that sadness; houses can be in disrepair, with rotting wood and untended yards. You can use weather in the same way. A bright, powerfully sunny day can reflect a mood of great cheer in a character.

• Show the impact of the setting on the character.

Say your character is in a prison cell; use the description of the surroundings to show how they shape the character's feelings. "He gazed at his cell: the uncomfortable, flat bed, the walls that squeezed around him, the dull gray color that pervaded everything."

The scene launch happens so quickly and is so soon forgotten that it's easy to rush through it, figuring it doesn't really matter how you get it started. Don't fall prey to that kind of thinking. Take your time with a scene launch. Craft each one as carefully and strategically as you would any other aspect of your scene. Remember that a scene launch is an

invitation

to the reader, beckoning him to come further along with you. Make your invitations as alluring as possible.

Where, exactly,

is

the middle of a scene? The term

middle

is misleading because scenes vary in length and there is no precise midpoint. The best explanation is to think of each scene's middle as a realm of possibility between the scene opening and its ending, where the major drama and conflict of the scene unfolds.

Be wary, because the middle has a seductive power to tempt writers into narrative side roads and pretty flower beds of words which, like those poppies in

The Wizard of Oz,

make the reader want to drift off to sleep.

If you grabbed the reader's attention with an evocative scene launch, the middle of your scene is the proving ground, the Olympic opportunity to hook the reader and never let her go.

UP THE ANTE: COMPLICATIONS

You are probably a very nice person who loathes the idea of even accidentally causing harm to another person. While this kindness is noble in life, in fiction writing it's a liability. You

must

complicate your characters' lives, and you must do it where the reader can see it—in scenes. Doing so is known as upping the ante. That phrase is most often heard in gambling circles when the initial bet goes up, making the potential win greater, along with the risk. What you must ante up in your scenes are those things your characters stand to lose (or even gain), from pride, to a home, to deep love. When you up the ante, you build anticipation, significance, and suspense that drive the narrative forward and bring the reader along for the ride.

This process is both terrible and wonderful. Terrible, because you must hurt your characters—you must take beloved people and possessions away from them, withhold desires, and sometimes even kill them for the sake of drama or tension. Yet it is also wonderful, because mucking about in your characters' lives will make the reader more emotionally invested in them.

In its simplest form, a traditional fictional narrative, whether story or novel, should address a problem that needs to be resolved or a situation that needs to be understood. Something like these: A young girl finds herself pregnant and abandoned by her family and her lover, so she falls into a life of prostitution on her road to spiritual redemption; a relative dies and leaves all his money to one family member, which launches a family feud; parents turn around at the mall and discover their child missing. The problem or situation must also include or encompass smaller problems (often called plot points) with consequences, which is where scenes come in.

Earlier, I mentioned the need to set scene intentions (see chapter eleven for more on scene intentions). An intention is your direction to yourself as to what aspect of the larger plot problem you will set into play in a given scene. Remember, your scenes transform flat ideas into experiences for the reader.

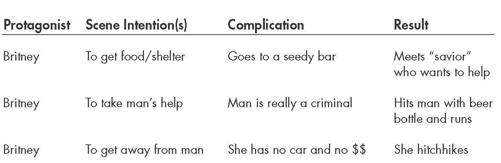

Let's walk through the nebulous middle of a scene, complicating as we go, using one of the examples above—that of the pregnant girl abandoned and left without resources.

Let's call your pregnant protagonist Britney. Resist the easy way out, which would be to narrate in flat prose that "Britney did some difficult and compromising things to take care of herself." Just get right to the work of revealing her plight in vivid scenes.

Start in a logical place—bereft Britney needs to obtain food and shelter so she can figure out what to do with her life. This will be her scene intention, her motivation. Therefore, she will need to go somewhere and do something to get that need met. Now remember your ingredients from chapter one: Britney, your character, stumbles into a physical setting—a dive bar, which you will be sure to describe in all its grimy, low-lit glory. You will be sure to reveal

through her point of view—probably the first or third person—that she has chosen this location because she knows she can garner the attention of men, whom she feels are most likely to help her out. You will hopefully show the surprised responses of the men and the bartender, some parrying dialogue, some cat-calling and general reactions to her presence—all of which is action. Then, as she stands there huddled against a barstool, frightened and unsure, a seedy looking man approaches her—and so your drama begins.

Perhaps this man makes her an indecent proposal—to do something she does not find palatable in return for money—and she is desperate enough to consider it. This is a complication. You have just upped the ante, and she now has something to lose—possibly her health, integrity, or her morality—in order to gain what she needs—money, food, and shelter. The reader will worry for her, which creates suspense and anticipation. The reader will not be able leave this poor girl's side; they will have to know what happens next.

And what will happen next? First, remember that the reader is your omnipresent witness. Don't draw the curtain between yourself and him and then report back passively later. Don't stop the complications either. Though you may want the bar fellow to turn out sweet and help Britney out of the kindness of his heart (because you love your character), the middle of your scene is no place for him to turn out to be a saint. Save that for a surprise ending. Scenes need dramatic tension in order to enact their tugging power on a reader. If he turns out nice, the reader can put down your narrative and sleep easy, and you don't want that!

Consider using a handy little graph that one of my editing clients found useful for working out complications in her scene middles. Make four columns and rows on a page like so (they can be longer rows than these):

A scene can unfold in a couple of paragraphs or two dozen pages. As long as Britney is engaged in the action with this seedy stranger in fictional real time—a streamlined series of events without a break in time—and in a single location (the interior of a moving car or other vehicle counts as a single location), your scene can be as long as it needs to be.

You need to make whatever happens to Britney in this scene complicated enough that it compels the reader to go on to the next scene or chapter. And you have the same task ahead of you for future scenes.

TECHNIQUES TO UP THE ANTE

Learning how to torture your characters and complicate their lives takes practice and a bit of a thick skin, which can be built up. A note of warning: While complications build anticipation and drama, you should not make things difficult on characters just because; complications have to reveal character and push your plot forward. It's hard to be cruel, so here are some specific techniques to add complications to your characters' lives in the middle of scenes.

The Withhold

Your characters need goals, desires, and ambitions to appeal to the reader's sensibilities. But to create the juicy tension that keeps a reader turning pages, you must dangle the objects of desire just out of reach at times, using a technique known as withholding.

There are many things you can withhold in scenes, such as emotions, information, and objects. Let's take a closer look at each.