Madonna (40 page)

Authors: Andrew Morton

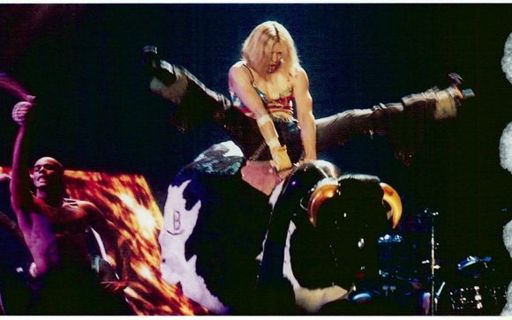

Madonna, the all-American girl, riding high in her 2001 Drowned World tour.

Mainstream Ferrara is not, and Madonna was taking a creative risk in agreeing to work with a director variously described as ‘talented and fiercely independent,’ but also as a ‘scuzzmeister,’ ‘decadent,’ or simply an incoherent drunk. She liked the script for his latest film, provisionally entitled

Snake Eyes

, and decided that her new film company, part of her Maverick empire, should part-finance the $10 million budget, though whether this was an act of artistic indulgence or a courageous leap of faith is difficult to determine. For years she had complained that as an actress she was just a brush in the hands of the director who was responsible for painting the resultant picture. Just as she had been in complete control of the text, design, production and photography of her first publishing venture, Sex, so she now expected a greater say in the direction and shape of the film her company was funding.

Certainly the original script and casting suited her, allowing her to work with two actors she knew and admired, Harvey Keitel and James Russo, the latter one of her ex-husband’s best friends, on a story in which her character, an actress named Sarah Jennings, emerges the winner, a strong woman triumphing over the evil that men do. ‘It was a great feminist statement and she [the principal character] was so victorious in the end,’ Madonna said of the original script. It was an intelligent screenplay, employing the concept of filming a movie about the filming of a movie, with each actor playing dual roles within the film. The plot is centered on a director, played by Keitel, making a film about a failed marriage, while his own marriage ‘off-screen’ is falling apart. At the same time Madonna plays a successful actress-cummistress in the film within a film, and a whimpering, abused wife who eventually triumphs over the violent verbal and physical interplay between Keitel’s director and Russo’s actor and pimp husband. ‘For an actress the role bore a resemblance to going over Niagara Falls in a barrel,’ observed the writer Norman Mailer, who interviewed her, going on to describe Madonna as a rarity among celebrities in that she did not select roles to buttress her status.

The film’s eventual title,

Dangerous Game,

was to prove apt, however. She was playing a dangerous game jousting with indomitably cussed individuals like Keitel and Ferrara, for both the film and the process of making it were precisely the opposite of what she had planned. More than that, the movie morphed into a commentary on Madonna herself, becoming a crude, if compelling, biography. ‘It’s a film about her as much as a film about what we were making because I forced her to confront many of the issues in her life,’ Abel Ferrara admits. ‘That’s why I went with Jimmy Russo as her husband because he’s Sean’s best friend. But no one even gets it.’ Certainly not Madonna, the critics or, for that matter, most of the audience. Some in her circle and those on the film set did appreciate what Ferrara was driving towards in this messy but fascinating work. ‘It was a movie about Madonna, we know this,’ notes the video producer Ed Steinberg, a friend of the director as well as of the singer. As Ferrara’s wife Nancy says of Madonna’s place in the film: ‘The people who worked for her, they got it.’

In an interesting artistic inversion, the perceived realism of Madonna’s documentary,

Truth or Dare,

merely recorded the essential artifice and staginess of her Blonde Ambition Tour, while Ferrara’s movie, supposedly an exploration of make-believe, ripped away her carefully contrived mask, the director literally wrenching a draining and difficult performance out of her. She never saw it coming. In the weeks before filming, which took place in the fall and winter of 1992, Madonna, ever the professional, carefully researched her part, visiting a home for battered women and numerous uptown churches, besides the occasion when she went out to get deliberately stoned.

When she arrived on set on the first day of filming she was line perfect and perfectly poised, every inch the star and the successful businesswoman. ‘The minute she walked into the room she took control,’ recalls Nancy Ferrara, although she adds, ‘but in a very positive way.’ Aware that, as leading lady she would have an intimate relationship with the director, she went out of her way to befriend his wife, sending Nancy a huge gift package of Dolce e Gabbana lingerie and a bottle of Chanel No. 5 for Christmas. ‘She won my heart,’ Mrs Ferrara admits.

Within minutes of the start of shooting, however, Madonna suffered a rude awakening. First of all Ferrara threw away most of the script and insisted on improvisation, urging the actors to explore not just the characters they were to play, but themselves. They spent hours discussing motivation, filming their discussions, filming themselves in the process of breaking themselves down. ‘I mean, I’m not getting my picture taken by fucking Richard Avedon right now, you know,’ a clearly tired and careworn Madonna says at one point in the finished film, the audience uncertain as to whether she is saying that as herself, or in character as the actress Sarah Jennings. The whole process was raw, uncompromising and dark, as much an exercise in group therapy as in shooting a film. A large part of the reason for this was because the movie, exploring themes of personal breakdown, was being shot as the marriages of Abel and Nancy Ferrara and Harvey Keitel and his wife Lorraine were in trouble in real life.

‘In the beginning she wanted to read the script, do the lines and that was it. Start at ten, go home at five. Goodbye,’ Nancy Ferrara says of Madonna. ‘It was not just the lines – the lines were the last and most meaningless thing in this. Abel and Harvey started really to get into the emotion and she was very apprehensive about going forward with that. She really held back a lot, she didn’t like it at all. She just never expected that and had never worked that way before. Somewhere in the first three months they broke her down and she got into it.’

Every day became a battle of wills between Madonna and Ferrara, on one occasion ending in a fight. ‘She tried to control me but she didn’t have a chance,’ Ferrara observes. ‘I’ve gone up against the baddest producers and toughest actors and it ain’t going to happen. The minute I lose control on the set then I’m useless to them and to her. She tried, she tried the whole time. I fucking hit her on the set even though I promised myself that I wouldn’t ever touch her. She made it sound like I almost killed her. I pushed her.’

For Madonna, the whole business was as infuriating as it was traumatic, for the sprawling, incoherent film-making process completely cut across the grain of her well-ordered personality. She complained that her director and fellow actors were drunk on the set, Ferrara often sitting in a corner drinking a glass of wine and letting the movie direct itself, and railed against the laissez-faire attitude during filming, as well as what she saw as the mood of misogyny both in the movie and on the set.

She had reason for complaint. Ferrara laughs knowingly when asked about the story that he picked the ugliest, smelliest film-crew member to simulate having sex with her for a scene that eventually ended up on the cutting room floor. ‘Abel is a misogynist,’ says his wife. ‘He grew up in a house full of women who treated him like a god. He has to have women around him but he hates them. They are a necessary evil.’

At the film’s end, her screen character, far from being victorious, is portrayed as defeated, weary and submissive, waiting passively for her violent husband to shoot her in the head. She is everything that Madonna is not. The film, however, is as much an exploration of the singer’s own personality as that of her screen character. In a quiet interlude she talks to Keitel about memories of the real rape she experienced in New York years earlier. Her screen husband, Russo, is portrayed as hard-drinking, abusive and out of control, violently cutting off her hair in one scene, eventually killing her. Parallels with Sean Penn and the genuine drama of their marriage breakup are unavoidable. ‘I’ve seen you suck the cocks of CEOs,’ Russo yells at her on screen. At a time when, in real life, she was being accused of simply publishing, with Sex, pornography for profit, the ‘director’ Keitel forces her, in her screen-actress persona, to admit that she is ‘nothing but a commercial piece of shit.’ In another scene Russo says of Madonna’s character: ‘We both know she’s a fucking whore and she can’t act.’ The very ambiguity of these and other scenes, whether they relate to Madonna or to her character, merely adds to the intrigue; art describing, and often imitating, a celebrity life.

When Madonna saw how the film had been edited, she became almost hysterical, not content with simply sending Ferrara vitriolic faxes, but also screaming her fury at him over the phone. Her own opinion of the film and its director takes no prisoners. In an interview she said: ‘He edited out all the brilliant things I said telling Harvey and James’s characters to fuck off. He took my words off me and turned me into a deaf mute. When I saw the cut film I was weeping. It was like someone punched me in the stomach. He turned it into

The Bad Director

. If I’d known that was the movie I was making, I’d never have done it. He really fucked me over.’

Although Ferrara was no less scathing about his co-producer – ‘She’s a fucking jerk. Like we sit around taking out the best scenes in the movie to spite her?’ – what is undeniable is that he and Keitel had teased, and sometimes almost bludgeoned, out of her one of the best and most revealing performances of her life. Perhaps that was why she took such exception to a film which, even at this distance, and for all its faults, has at its core a disturbing honesty – the ‘ickiness’ of life, and particularly her life, laid brutally bare. As Nancy Ferrara coolly and generously observes: ‘She looks very vulnerable and that was really pulling her apart. At the end she revealed that when she is not in control, she is not as secure or confident as she would like everyone to think. She revealed something of her humanity. It is one of her best films, fascinating because it says so much about her. That’s why she wouldn’t endorse it. It was too close to the bone. She hit on all that emotion and couldn’t face it.’

Dangerous Game,

released in the summer of 1993, marked a critical nadir for Madonna. She had been pounded by the adverse publicity surrounding Sex, published in October 1992, had suffered ridicule for her part in

Body of Evidence

, released in January 1993, and now faced up to another sheaf of terrible reviews for her first film as a co-producer. That she disowned her first cinematic baby did little to restore her radical chic – or to help the film’s commercial success. It grossed just $60,000 at the box office, one of the biggest flops of the year. She had taken genuine artistic risks in all these projects, revealing herself, personally, as well as physically, only to find herself written off by the critics and her public.

Nor was her musical career any longer in the first flush of youth. Her third single release from the

Erotica

album, ‘Bad Girl,’ reached a dismal thirty-sixth place in the charts, her lowest ever chart rating. Even friends in the music industry were concerned; as Michael Rosenblatt of Sire Records noted, with considerable understatement: ‘It wasn’t her high point artistically.’ To add insult to injury, the disco diva Donna Summer rejected an approach to cover her selected hits, telling Madonna that she would never give her the rights to sing her songs. It rankled too that, while she was taking on creative challenges and catching considerable critical flak, other singers rode her coattails. She always resented the fact that Janet Jackson seemed to copy her every move, imitating the mood of her pop videos or even using a director Madonna had collaborated with, in this case the photographer Herb Ritts, who had worked on her

Rain

video. Nor, after so many Hollywood mishits, could it help but hurt a little when Whitney Houston hit a double strike with her 1992 film

The Bodyguard,

both the movie and soundtrack single, ‘I Will Always Love You,’ becoming major hits.

As Madonna licked her wounds, cultural gurus and intellectuals were lining up to write her off. During the conservative Reagan years, so the argument ran, Madonna had reached a natural constituency with her fan base among young women, gays and blacks. Following the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the ending of the Cold War and the arrival of a Democrat in the White House, the world was a different place. It seemed that her time had come and gone.

With her latest projects

, Sex

, the

Erotica

album and now

Dangerous Game

, she had traveled from the mainstream to the margin, and was in danger of being marooned there. Previously cheerleading intellectuals abandoned the artist to a cultural twilight zone, while her own pronouncements, with their artful and knowing references to long-dead European film stars, artists and photographers, went over the heads of her mainstream fans. It appeared that her automatic place on university curricula as an identity who self-consciously defined modern popular culture, a knowing, winking icon of post-modernism, was no longer guaranteed.