Made In America (61 page)

Authors: Bill Bryson

Books by comparison showed much greater daring.

Fucking

appeared in a novel called

Strange Fruit

as early as 1945, and was banned in Massachusetts as a result. The publishers took the state to court, but the case fell apart when the defence attorney arguing for its sale was unable to bring himself to utter the objectionable word in court, in effect conceding that it was too filthy for public consumption.

46

In 1948 Norman Mailer caused a sensation by including

pissed off

in

The Naked and the Dead.

Three years later, America got its first novel to use four-letter words extensively when James Jones’s

From Here to Eternity

was published. Even there the editors were at sixes and sevens over which words to allow. They allowed

fuck

and

shit

(though not without excising about half of such appearances from the original manuscript) but drew the line at

cunt

and

prick.

47

Against such a background dictionary makers became seized with uncertainty. In the 1960s the

Merriam-Webster Dictionary

broke new ground by including a number of taboo words –

cunt, shit

and

prick

– but lost its nerve when it came to

fuck.

Mario Pei protested the omission in the

New York Times

but of course without once mentioning the word at issue. To this day America remains to an extraordinary degree a land of euphemism. Even now the US State Department cannot bring itself to use the word

prostitute.

Instead it refers to ‘available casual indigenous female companions’.

48

Producers of rape-seed are increasingly calling it

canola,

lest the first syllable offend any delicate sensibilities, even though

rape

in the horticultural sense comes from rāpa, Latin for ‘turnip’.

49

Despite the growing explicitness of books and movies, in most other areas of public discourse – notably in newspapers, radio and local and network television – America remains perhaps the most extraordinarily cautious nation in the developed world. Words, pictures and concepts that elsewhere excite no comment or reaction remain informally banned from most American media.

In 1991 the

Columbia Journalism Review

ran a piece on the coverage of a briefly infamous argument between Pittsburgh Pirates Manager Jim Leyland and his star player Barry Bonds. It examined how thirteen newspapers from around the country had dealt with the livelier epithets the two men had hurled at each other. Without exception the papers had replaced the offending words with ellipses or dashes, or else had changed them to something lighter – making ‘kissing your ass’ into ‘kissing your butt’, for instance. To an outside observer there are two immediately arresting points here: first, that ‘kissing your ass’ is still deemed too distressingly graphic for modern American newspaper readers, and, secondly, that ‘kissing your butt’ is somehow thought more decorous. Even more arresting is that the

Columbia Journalism Review,

though happy to revel in the discomfort at which the papers had found themselves, could not bring itself to print the objectionable words either, relying instead on the coy designations ‘the F-word’ and ‘the A-word’.

Examples of such hyperprudence are not hard to find. In 1987 the

New York Times

columnist William Safire wrote about the expression

cover your ass

without being able to bring himself to record the phrase, though he had no hesitation in listing many expressive synonyms:

butt, keister, rear end, tail.

In the same year, when a serious art-house movie called

Sammy and Rosie Get Laid

was released, Safire refused to name the film in his column (the

New York Times

itself would not accept an ad with the full title). Safire explained: ‘I will not print the title here because I deal with a family trade; besides, it is much more titillating to ostentatiously avoid the slang term.’

50

Pardon me? On the one hand he wishes to show an understandable consideration for our sense of delicacy; but on the other he is happy to titillate us – indeed, it appears to be his desire to heighten our titillation. Such selective self-censorship would seem to leave American papers open to charges of, at the very least, inconsistency.

In pursuit of edification, I asked Allan M. Siegal, assistant managing editor of the

New York Times,

what rules on bad language obtain at the paper. ‘I am happy to say we maintain no list of proscribed expressions,’ Siegal replied. ‘In theory, any expression could be printed if it were central to a reader’s understanding of a hugely important news development.’ He noted that the

Times

had used

shit

in reports on the Watergate transcripts, and also

ass, crap

and

dong

’in similarly serious contexts, like the Clarence Thomas sexual harassment hearings’.

Such instances, it should be noted, are extremely exceptional. Between 1980 and July 1993,

shit

appeared in the

New York Times

just once (in a book review by Paul Theroux). To put that in context, during the period in review the

Times

published something on the order of 400 million to 500 million words of text.

Piss

appeared three times (twice in book reviews, once in an art review).

Laid

appeared thirty-two times, but each time in reference to the movie that Safire could not bring himself to name.

Butthead

or

butthole

appeared sixteen times, again almost always in reference to a particular proper noun, such as the interestingly named pop group

Butthole Surfers.

As a rule, Siegal explained, ‘we wish not to shock or offend unless there is an overweening reason to risk doing do. We are loath to contribute to a softening of the society’s barriers against harsh or profane language. The issue is nothing so mundane as our welcome among paying customers, be they readers or advertisers. Our management truly believes that civil public discourse is a cherished value of the democracy, and that by our choices we can buttress or undermine that value.’

51

One consequence of the American approach to explicit language is that we often have no idea when many of our most common expressions first saw light since they so often go unrecorded. Even something as innocuous as to be

caught

with one’s pants down

isn’t found in print until 1946 (in the

Saturday Evening Post

), though it is likely that people were using it at least a century earlier.

52

More robust expressions like

fucking-A

and

shithead

are effectively untraceable.

Swearing, according to one study, accounts for no less than 13 per cent of all adult conversation, yet it remains a neglected area of scholarship. One of the few studies of recent years is

Cursing in America,

but its author, Timothy Jay of North Adams State College in Massachusetts, had to postpone his research for five years when his dean forbade it. ‘I was told I couldn’t work on this and I couldn’t teach courses on it, and it wouldn’t be a good area for tenure,’ Jay said in a newspaper interview.

53

‘The minute I got tenure I went back to dirty words.’ And quite right, too.

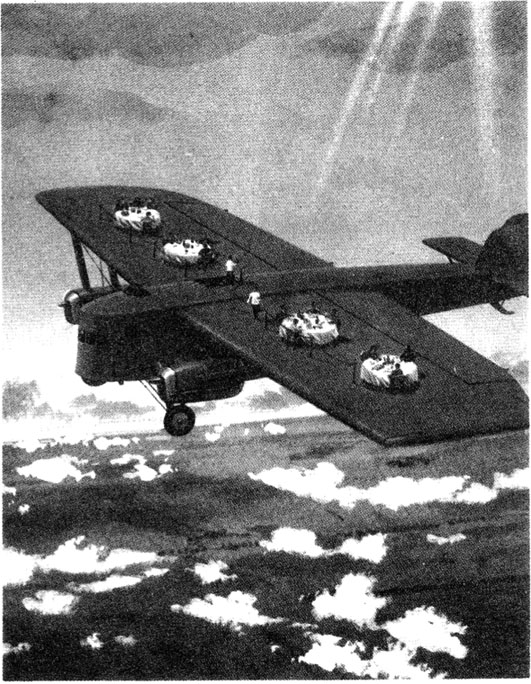

Wing dining, somewhere over France, 1929

The Road from Kitty Hawk

The story is a familiar one. On a cold day in December 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright, assisted by five locals, lugged a flimsy-looking aircraft on to the beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. As Wilbur steadied the wing, Orville prostrated himself at the controls and set the plane rolling along a wooden track. A few moments later, the plane rose hesitantly, climbed to about 15 feet and puttered along the beach for 120 feet before setting down on a dune. The flight lasted just twelve seconds and covered less ground than the wing-span of a modern jumbo jet, but the airplane age had begun.

Everyone knows that this was one of the great events of modern technology, but there is still a feeling, I think, that the Wrights were essentially a pair of inspired tinkerers who knocked together a simple contraption in their bike shop and were lucky enough to get it airborne. We have all seen film of early aircraft tumbling off the end of piers or being catapulted into haystacks. Clearly the airplane was an invention waiting to happen. The Wrights were just lucky enough to get there first.

In fact, their achievement was much, much greater than that. To master powered flight, it was necessary to engineer a series of fundamental breakthroughs in the design of wings, engines, propellers and control mechanisms. Every piece of

the Wrights’ plane was revolutionary, and every piece of it they designed and built themselves.

In just three years of feverish work, these two retiring bachelors from Dayton, Ohio, sons of a bishop of the United Brethren Church, had made themselves the world’s leading authorities on aerodynamics. Their home-built wind tunnel was years ahead of anything existing elsewhere. When they discovered that there was no formal theory of propeller dynamics, no formulae with which to make comparative studies of different propeller types, they devised their own. Because it is all so obvious to us now, we forget just how revolutionary their concept was. No one else was even within years of touching them in their mastery of the aerodynamic properties of wings. Their warping mechanism for controlling the wings was such a breakthrough that it is still ‘used on every fixed-wing aircraft that flies today’.

1

As Orville noted years later in an uncharacteristically bold assertion, ‘I believe we possessed more data on cambered surfaces, a hundred times over, than all of our predecessors put together.’

2

Nothing in their background suggested that they would create a revolution. They ran a bicycle shop in Dayton. They had no scientific training. Indeed, neither had finished high school. Yet, working alone, they discovered or taught themselves more about both the mechanics and science of flight than anyone else had ever come close to knowing. As one of their biographers put it: ‘These two untrained, self-educated engineers demonstrated a gift for pure scientific research that made the more eminent scientists who had studied the problems of flight look almost like bumbling amateurs.’

3

They were distinctly odd. Pious and restrained (they celebrated their first successful flight with a brief handshake), they always dressed in business suits with ties and starched collars, even for their test flights. They never married, and always lived together. Often they argued ferociously. Once, according to a colleague, they went to bed heatedly at odds

over some approach to a problem. In the morning, they each admitted that there was merit in the other’s idea and began arguing again, but from the other side. However odd their relationship, clearly it was fruitful.

They suffered many early setbacks, not least returning to Kitty Hawk one spring to find that a promising model they had left behind had been rendered useless when the local postmistress had stripped the French sateen wing coverings to make dresses for her daughters.

4

Kitty Hawk, off the North Carolina coast near the site of the first American colony on Roanoke Island, had many drawbacks – monster mosquitoes in summer, raw winds in winter, and an isolation that made the timely acquisition of materials and replacement parts all but impossible – but there were compensations. The winds were steady and generally favourable, the beaches were spacious and free of obstructions, and above all the sand-dunes were mercifully forgiving.

Samuel Pierpont Langley, the man everyone expected to make the first successful flight – he had the benefits of a solid scientific reputation, teams of assistants, and the backing of the Smithsonian Institution, Congress and the US Army – always launched his experimental planes from a platform on the Potomac River near Washington, which turned each test launch into a public spectacle, and which then became a public embarrassment as his ungainly test craft unfailingly lumbered off the platform and fell nose first into the water. It appears never to have occurred to Langley that any plane launched over water would, if it failed to take wing, inevitably sink. Langley’s devoted assistant and test pilot, Charles Manly, was repeatedly lucky to escape with his life.

The Wright brothers by contrast were spared the pestering attention of journalists and gawkers and the pressure of financial backers. They could get on with their research at their own pace without having to answer to anyone. And when their experimental launches failed, the plane would

come to an undamaged rest on a soft dune. They called their craft the Wright Flyer – named, curiously enough, not for its aeronautical qualities but for one of their bicycles.

By the autumn of 1903, the Wright brothers knew two things: that Samuel Langley’s plane would never fly and that theirs would. They spent most of the autumn at Kitty Hawk – or more precisely at Kill Devil Hills, near Kitty Hawk – readying their craft, but ran into a series of teething problems, particularly with the propeller. The weather, too, proved persistently unfavourable. (On the one day when conditions were ideal they refused to fly, or do any work, because it was a Sunday.) By 17 December, the day of their breakthrough, they had been at Kitty Hawk for eighty-four days, living mostly on beans. They made four successful flights that day, of 120, 175, 180 and 852 feet, lasting from twelve seconds to just under a minute. As they were standing around after the fourth flight, discussing whether to have another attempt, a gust of wind picked up the plane and sent it bouncing across the sand-dunes, destroying the engine mountings and rear ribs. It never flew again.