Madame de Pompadour (33 page)

Read Madame de Pompadour Online

Authors: Nancy Mitford

Maria Theresa was, of course, very much pleased by the appointment of Choiseul. She knew him well and had always known his family – his father had at one time been Austrian Ambassador to France – so she could be quite sure that he would never go back on the alliance. She now sent Madame de Pompadour the famous

escritoire

. When she first had the idea of giving the Marquise a present, she seems to have asked Starhemberg whether he thought a sum of money or a diamond aigrette would be the best. He replied that in his view the present that would give most pleasure

would

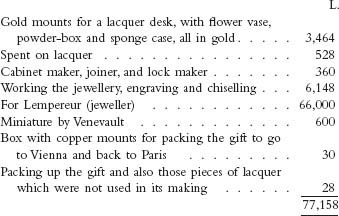

be one of the new writing tables now so fashionable, upright in design; these could be bought in Paris for about 4,000 ducats. The Empress did not consider this valuable enough; she said it should cost at least 6,000 ducats. She chose, out of her own enormous collection of lacquer boxes, two of the most perfect, and sent them to Paris to be made up and mounted in gold. This was done by the jeweller Ducrollay, Place Dauphine, and here is his bill.

The miniature of the Empress, surrounded by diamonds, was evidently set in the lacquer. Nobody knows what finally became of this remarkable piece mounted, it will be noticed, not in ormolu but in solid gold. Madame de Pompadour complained that it was really too rich and that she had to hide it for fear of gossip; she removed the miniature and had it framed in silver gilt, and thus it appears in the inventory of her belongings made after her death. But the

escritoire

itself seems to have vanished for ever.

Madame de Pompadour asked Starhemberg if she might take the unusual liberty of writing direct to the Empress to thank her for this present. ‘… If to be penetrated with enthusiastic admiration, Madame, for Your Imperial Majesty’s charm and legendary virtues is to be worthy of this precious gift then nobody can be more worthy than I …’ She signed Jeanne de Pompadour,

28

January 1759, instead of her usual signature, Marquise de Pompadour. (Letters to her relations and great friends had no beginnings or endings, they were sealed with her three castles.)

Frederick, whose spies got hold of a copy of the letter for him, circulated a parody which caused him the most exquisite delight: ‘Beautiful Queen, the gracious words it pleases Your Majesty to write to me are beyond all price. Incomparable Princess, who honours me with the title of

bonne amie

, would that I could reconcile you to Venus the Goddess of Love as I have reconciled you to my country …’ and so on.

This did not do much harm to his victim; if anybody suffered it was Maria Theresa who has been said by quite reputable historians to have written ‘chère amie’ and even ‘chère cousine’ to Madame de Pompadour. Of course she never wrote directly to her at all. The parody was rushed from the drum on which it was written to the printing presses in Holland, and sent to all the German states. Various copies went to Paris in the hope that one, at least, would find its way to Versailles.

Voltaire was now back in Madame de Pompadour’s life, a reconciliation between them having been made by Choiseul, who was a friend of his. In 1760 he dedicated

Tancrède

to her: ‘Ever since your childhood I have seen distinction and talents developing in you. At all times you have been unchangingly good to me. It must be said, Madame, that I owe you a great deal; furthermore I venture to thank you publicly for all you have done to help a large number of writers, artists and other categories of deserving people … You have shown discernment in doing good because you have always used your own judgment. I have never known a single writer or any unprejudiced person who has not done justice to your character, and this not only in public but also in private conversations when people are much more inclined to blame than to praise. Believe me, Madame, it is something to be proud of that those who know how to think should speak thus of you.’ No woman could ask for a greater tribute from a man of genius.

On 10 March 1762, Jean Calas, a Protestant draper of Toulouse, suffered the dreadful death of being broken on the wheel. He had

been

convicted of hanging his own son because he thought he was about to become a Roman Catholic. His guilt was impossible; morally, because Calas was a gentle creature, devoted to his children: physically, because he was weak and old and his son was a hearty young man of twenty-eight; legally, because there was not a shadow of proof – on the contrary it was evident that young Calas, who was given to fits of depression, had committed suicide. Toulouse was one of the most fanatically anti-Protestant towns in France; its

Parlement

had condemned Calas from religious bigotry.

When Voltaire heard this story he worked himself into a frenzy of rage. It offended him in his deepest feelings, as a crime committed in the name of God. Calas was dead and could not be brought back to life, but his widow and remaining children were in the greatest distress: their wordly goods had been confiscated; two young girls taken from their mother and shut up in convents; and one son banished. Voltaire set to work to get the verdict reversed and the family rehabilitated; in the conduct of this case he appears at his very best. Not only does an extreme goodness inform every step he took but also a knowledge of the world in which he had hitherto seemed deficient. He needed, and sought the help of his many highly placed friends. Madame Calas was a tiresome person, so timid that she gave the impression that she would really prefer the whole matter to be dropped. Voltaire never lost patience with her; he lent her money; made his Paris friends look after her; wrote letters for her to send off at a suitable time; he sometimes complained of her but was never cross with her. Many of his correspondents were on his side and helped as much as they could; some behaved like comfortable, selfish, rich people the world over. The exiled Bernis, the Ducs de Choiseul and de Villars all wrote saying: ‘Don’t get so excited – magistrates never sentence people to death for their own amusement – no smoke without fire.’ Choiseul, however, came round to Voltaire’s way of thinking in the end. (It is interesting to note that, to begin with, the line-up of opinion was much the same as when, nine years later, the King was trying to suppress the

Parlements

and reform the Constitution: Voltaire, the

philosophes

, the more enlightened Magistrates and the King against practically the whole of the aristocracy and the

bourgeoisie.

That Louis XV died before his plans could be implemented is one of the tragedies of history.)

Voltaire’s timing in the Calas affair was faultless. When the right moment came, not too soon, he sent somebody to explain the matter to Madame de Pompadour. Her feelings are expressed in a letter to the Duke of FitzJames:

Yes indeed, M. le Duc, the story of poor Calas makes one shudder.

One should pity him for being born a Protestant but that’s no reason for treating him like a highwayman.

It seems impossible that he should have committed the crime of which he was accused; it would be too unnatural.

However, he is dead, his family is blighted and his judges are unrepentant.

The King, in his goodness, has suffered over this business and all France is crying out for vengeance.

The wretched man will be avenged but can’t be brought back to life.

These people of Toulouse are too fanatical to be good Christians. May God convert and give them a little humanity.

Adieu, M. le Duc, I am your sincere friend.

La Mse. de Pompadour, Versailles, 27 Aug: 1762.

The Toulouse

Parlement

fought every inch of the way but public opinion was now against it. Madame Calas and her daughters went to Versailles, were presented to the Queen and made much of by the courtiers. The King was too shy to see them. However, on 1 March 1763, he called a Council and decided that the affair should go to the

Cour des Requêtes

. There was an outcry against this move – the Crown seemed to be overruling the Law – but Louis XV took no notice and finally the judgment against Calas and his family was quashed; no one was ever broken on the wheel again in France. The King gave a handsome sum of money to Madame Calas. Madame de Pompadour had done all she could to bring this about and Voltaire forgave her for befriending Crébillon.

But the Marquise had begun to have doubts about the

philosophes

. ‘What has come over our nation?’ she wrote during the defeats of the Seven Years’ War. ‘The

parlements, encyclopédistes

and so on have changed it utterly. When all principles have gone by the board, when neither King nor God are recognized, a country becomes nature’s pariah.’ All the years she had spent at Court had made her more royalist than the King.

Frederick soon discovered that Madame de Pompadour and Voltaire were writing to each other again and began to use Ferney as a post office for Versailles. Choiseul was anxious to make peace, if it could be an honourable one, and he told Voltaire to see if Frederick could not be persuaded to reduce his demands and those of his English allies. ‘Tell the King that, in spite of our set-backs, Louis XV is still in a position to wipe out the state of Prussia. If peace be not made this winter we shall be obliged to take this decision, however dangerous.’ He added that France would be prepared to pay an indemnity.

Frederick pretended not to be interested in these overtures; Choiseul would soon be sent away, he said – he had already been minister for two years, a record at the French Court. Choiseul, thoroughly nettled, declared that he hated politics worse than death and lived only for pleasure; exile held no terrors for him. He had a beautiful house, a charming and faithful wife and delicious mistresses; there were only two ways in which anybody could harm him. The first would be to make him impotent and the second to oblige him to read the works of the philosopher of Sans-Souci. Frederick’s reply was that peace would be signed – yes, by the King of England in Paris and by himself in Vienna. After this the letters became so acid that Voltaire stopped forwarding them; he saw that both sides would very soon round on him in their fury if he continued to be the go-between.

Choiseul’s contribution to foreign policy was the

Pacte de Famille

among the Bourbons who reigned over France, Spain, Parma, Naples and the Two Sicilies; it was a Latin and Catholic bloc, fortified by an even closer alliance with the Empire, which was now drawn into the family. Louis XV married the two daughters of Madame Infante to the Emperor Joseph II and the Prince of

the

Asturias, while three little Archduchesses, in time, became Duchess of Parma, Queen of Naples and Dauphine of France.

The alliance between France and Spain, so ardently desired for so long, came too late to be of much use; Spain, exhausted by her efforts in the New World, had fallen a victim to the Roman Catholic religion in its most deadening and reactionary form, and had ceased to have much international importance. She was really more of a hindrance than a help to France in the war against England. As the war dragged on, it became obvious that the only course for Louis XV was to make the best peace he could, to build up a navy and perhaps resume the fight when England began to have difficulties with her American subjects. These difficulties were already foreseen by all the European statesmen of the day.

In 1762 the Empress Elizabeth of Russia died and her successor, Peter III, immediately made peace with Frederick, his hero from an early age. The withdrawal of Russia led to that of Sweden. All the European powers were sick of this apparently inconclusive war in which nearly a million people had perished. An armistice was agreed upon in 1762 and peace on a

status quo ante

basis was signed (February 1763).

The fall of Pitt’s government in 1762, and the fact that the new King, George III, seemed in favour of peace, decided the French to open negotiations with England. In September the Duc de Nivernais, ‘crowned like Anacreon with roses and singing of pleasure’, set out for London as plenipotentiary. He very soon changed his tune. Most Englishmen were for continuing the war until they had taken the last inch of colonial territory from France. Nivernais’ first night in England, at a delightful inn at Canterbury, cost him forty-six guineas; this extortion was the innkeeper’s way of showing his patriotism. (When the gentlemen of Kent found it out they boycotted the inn and Nivernais eventually had to come to the rescue of his robber, now reduced to starvation, with a large gift of money.) The journey to London, however, charmed him, he said the country was all cultivated like the King’s kitchen gardens. The Duke of Bedford’s coachman took him, at an amazing speed, to the magnificent bridge of Westminster. Bedford himself had gone as envoy to France and made use of Nivernais’ coaches while

he

was there – the usual arrangement between ambassadors in those days, who often used to live in each other’s houses. Mirepoix and Albemarle had done so before the war began. Bedford left two houses ready for Nivernais, one in and one just outside London, ‘very ugly but well situated’.

So far so good. But the smoke of London got on Nivernais’ nerves, the fogs gave him a chronic sore throat and he could not bear the hours spent over the port after every meal. Very soon he took to leaving the table with the women; he would recite verses composed specially for them, or play the violin to them, in the drawing-room. They must have been surprised. Worst of all, Englishmen were extremely awkward to treat with, and things were not made easier by the fall of Havana. The news of this victory arrived when Nivernais was dining with Lord Bute; his fellow guests, unmindful of his feelings, burst into loud cheering.