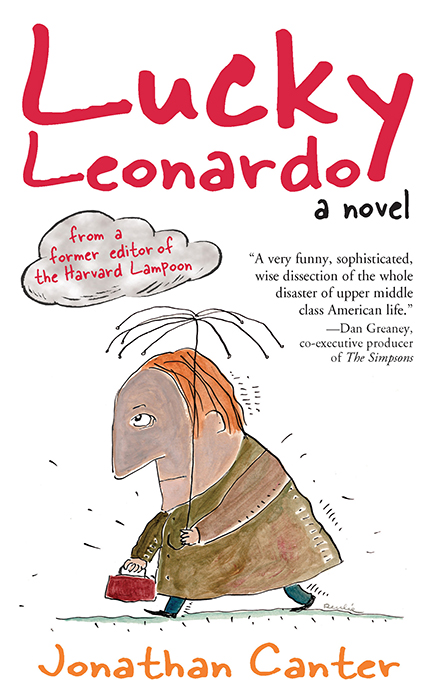

Lucky Leonardo

Authors: Jonathan D. Canter

Cover and internal design © 2004 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover photo © Corbis

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsâexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewsâwithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

FAX: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Canter, Jonathan D.

Lucky Leonardo : a novel / by Jonathan D. Canter.

p. cm.

(alk. paper)

1. PsychiatristsâFiction. 2. Divorced menâFiction. 3. Loss (Psychology)âFiction. 4. Suicide victimsâFiction. I. Title.

PS3603.A579L83 2004

813'.6âdc22

2004013182

To Ronda, without whom nothing.

“Bill, come back,” William Brockleman's former secretary Selma Floyd screamed at his descending casket. “Bill, please come back,” she screamed from her knees as she leaned over the fresh hole with her skirt riding up her thighs and rouge and tears streaming down her cheeks, looking not exactly like the caring colleague come to pay respects, not exactly like the saddened friend offering condolence to the grieving family, more like the paramour corrupted by her passion to expose herself.

Brockleman's widow stood on the far side of the hole eyeballing Selma and the rest of the incomprehensible new world that was cracking open in front of her in the wake of her husband's death. She wobbled forward like she might jump in to join her husband or across to whack Selma before collapsing backwards instead into the arms and lap of her teenage son, in a whoosh of widow's weeds.

Such a scene that those who knew nothing except what they saw with their own two eyes wanted to know more. Like since when and how often? In a better world a smiling reporter might be graveside with back story and photographs, but in the imperfect here and now from which Brockleman recently departed, those raising eyebrows as his big, walnut casket dropped below the shoe line had to settle for commentary from his former clients, Janet Casey and her crotchety boss Mulverne. “She's the one,” Janet said pointing at bereft and exposed Selma, “who the bastard left in serious trouble.”

“She looks like she finds serious trouble all by herself,” Mulverne replied in his crow's croak of a whisper, which was loud enough to be heard by everyone except Brockleman, assuming Selma failed in her attempt to arouse him, and Brockleman's widow who stayed sprawled in her son's lap on the soundproof side of consciousness.

Poor Brockleman. They found him frozen stiff, a frozen stiff, slumped over the steering wheel of his big Mercedes at a highway rest stop. His wallet was missing, which delayed identification and gave rise to the initial flurry of speculation of foul play. But Janet Casey delivered the wallet to the widow early the next morning. Janet explained with a sad straight face that he had it out to pay the pizza delivery boy, and must have forgotten.

“He was eating pizza last night?” the widow asked. She was standing at her front door, still in her robe, with a cold wind blowing past her into the house. “With you?”

Janet nodded. There was a lot the widow didn't know.

In a cool, shaded room, three months earlier.

A woman spoke to a man. “â¦My large breasts were famous in high school,” she said, pointing at them with her forefingers in case of confusion as to their whereabouts. “Like they were stared at all the time, like I was a hunchback or had some disgusting skin disease. Whenever I walked down a corridor I heard snickers and stupid farting sounds behind my back. One homecoming the big joke was to see if someone could snatch my brassiere⦔

The man nodded. The woman continued.

“My breasts were asked out almost every Saturday night, by boys who were generally pretty cool and good-looking. I went along on the dates, but a lot of the time I felt uninvited, like I knew and the boys knew that the only thing going on was whether they'd get a handful of breast before the end of the date, and all the other stuff about holding open the door of the car, and buying me popcorn, and chitchatting about the movie was just to distract me⦔

The man nodded. The woman dabbed her eye with a tissue, and glanced down at her breasts with a look of irritation like they were trouble-makers, like they had given her more trouble over the years than they were worth, like if they didn't shape up she'd go through with the reduction surgery.

“My breasts just played along,” she said. “They filled the space between me and the boys like a dumb blonde. Like two dumb blondes. Like to this day I don't understand what the big deal was. So I had big breasts? Big fucking deal. I knew plenty of girls who would have gone down on those boys, on the cute ones anyway, and given them some real excitation. So why not date those girls instead of my breasts, which were just lifeless flesh with no chance whatsoever to suck or squeeze⦔

The man nodded. The woman continued.

“â¦Or give love in return, which I as a virginal adolescent was desirous of doing free from their grabbing, pawing, squeezing, disgusting hands. They'd grab my breast flesh like dogs chewing on a bone, and they held on while I squirmed, and pushed them off, and pinched⦔ She made a big pinching movement with her thumb and forefinger, like she was snapping at a fly. “â¦All my datesâmy breasts' datesâended with a guy's hand grabbing my breast and me crying⦔

The woman dabbed her eyes. Her lower lip started to tremble. “â¦I think,” she said, “making me cry felt as good to them as holding my breast. It was like they achieved

penetrationâ¦

”

The man nodded. There was moistness in his eyes. He was sincere. The woman released a sob, nearly a moan. Her face scrunched up. Tears began to flow. But she stopped herself. She eyed the man. “What do you think about them?” she asked, rolling her shoulders back so he could get a better view.

Hmm,

he thought, not for the first time.

A handful and an eyeful, thoughtfully displayed beneath a sheer silk blouse which plunged at the throat and tightened around the curve. A heavy burden, a heavy pendulous burden, for a shy girl to bear.

“What do you think I think?” he asked.

“I think you think I⦔ And then the dam burst. She was engulfed in her tears.

The man cast a glance to his clock, positioned on a shelf behind her shoulder so that he could keep track of time without noticeable deflection of his steady and concerned gaze. Just a few more minutes, he observed to himself, and sat placidly while she regained composure. When she was almost quiet and dry he said, “Tell me your thoughtsâ¦,” which provoked a new wave of tears continuing to the end of the session.

“Michelle, we have to end now,” he said softly. “I'll see you next Friday, same time?”

“Yes, Dr. Cook,” she said as she gathered herself together, straightened her skirt and blouse, blew her nose, and followed her breasts to the door.

He, Leonardo Cook, MD, forty-four year old psychiatrist, waited quietly and consolingly in his place until she and they cleared his waiting room, and he heard the outside door close behind, before he threw off his decorum like a pair of tight pants and dashed to the home part of his home/office to change for golf.

“Golf, golf, golf, always room for golf,” he sang to himself in the privacy of his bedroom, with relief he was done with work for the week and could relax his sympathy muscles, accompanied by a little golf dance which might have been observed and ridiculed by the squirrel family that was gathering nuts in his backyard if they had paused for a minute to take a look through the bedroom window. More on this view and this window later.

He was halfway out of his work clothes, singing, dancing, stripteasing, visualizing a slow back swing followed by a smooth and powerful thrust through the ball, when the phone rang. His private line, known only to a few.

“It will keep,” he said for two full rings, but during the third he weakened and reluctantly answered. “Dr. Cook here.”

“Bill Brockleman,” the caller, whose disrupted funeral we previously observed, said. “Do you have time this afternoon? I need you. I'm in a crisis.”

“Sorry, Bill,” Leonardo said firmly, “I can't help you. I have a tee time. Avoid open windows in tall buildings. Call me in the morning.”

The soon-to-be-late Brockleman thought that was funny, because he wasn't an open window kind of guy. He wasn't a patient. He was a lawyer Leonardo worked with on stinky legal problems wanting a psychiatrist, like last month when a rich old man was kidnapped by his children and incarcerated in an exclusive and secure elderly care facility to keep him from marrying his thirty-something (so she said) girlfriend. Brockleman represented the girlfriend. Leonardo testified at the injunction hearing that in his opinion the old man was competent to run his own life. “I realize,” Leonardo told the judge coolly and with analytical distance, “that he does not demonstrate strong verbal skills, and expresses himself mostly with grunts and waves of his good hand. But in my professional opinion he knows where he is, and who put him there, and why they put him there, and he's angry about it⦔

“Listen,” Brockleman said on the phone. “My client DeltaTek, the software company?”

“Yes,” Leonardo said, with trepidation, like his ball was rolling off the green in the direction of the water hazard.

“Their chief software designer has been acting erratic. Missing appointments, looking unkempt, talking to himself. They decide he needs a vacation. They tell him take two months, see a shrink, get medicated, then we'll talk. Couldn't have been nicer. But he snaps, barricades himself into his office...”

“Drag him out,” Leonardo said with wishful thinking, like he was urging his ball to stop right there on the side of the hill, but instead it was gathering speed.

“It's a hostage situation⦔

“Oh? He's pointing a gun at his secretary?”

“I wish,” said Brockleman. “Unfortunately he's threatening to email the company's secret software code

to the whole damn world.

I don't know shit about computers, doc, but they tell me this is Chernobyl⦔

“DeltaTek does nuclear technology?”

“No, no. I mean this is Hiroshima. No, what I mean is this is a big fucking disaster about to happen.”

“Why would he do something crazy like that?”

“Doc, that's why I'm calling you.”

“Shut off his power⦔

“He has back-up.”

“Jam him.”

“As if you know shit about jamming. Doc, forget your golf today. This is serious business. I told them they need you. You know how to talk to the nut-cakes.”

“Bill, you flatter me.”

“I told them you'd figure out how crazy he is, what he might do next, how to get him to take some medicine, how to get him to drop his mouse. The usual. They want to avoid going public, obviously. They're afraid this could scare the shit out of the stock price. They'll make it worth your while.”

“I wish you weren't so persuasive,” said Leonardo as the song, the dance, the slow back swing drifted away.

“So?”

“And I wish I weren't a pig for the money.”

Leonardo canceled his golf, and cruised north on Massachusetts Route 128, nicknamed America's Technology Highway by the locals, from his home/office in Newton to DeltaTek's corporate campus in Lexington, in the red Corvette he bought himself as a present the day his divorce from Barbara went final.

“Nice car,” she commented the first time he drove around to pick up their son Harvey for the weekend. She retained custody for twenty-two days each month, except for December when she had twenty-four, which along with the pardon given Richard Nixon topped Leonardo's lifetime list of most offensive rewards for wrongdoing.

“I hope it picks you up,” she added, “because I really don't want you to stay rolled up in a crumpled little ball for the rest of your life. But the thing is, I'm surprised my lawyer left you so much spending money. Either he screwed up or you failed to disclose your assets to the court. I'm going to have to ask some questions⦔

Barbara could be vicious, and in her dealings with Leonardo invariably was.

She moved in with her high school sweetheart Stan, a divorced music teacher, the night Leonardo discovered their adultery. “I feel this is where my home should be,” she told Leonardo once he stopped screaming after he emerged from the shrubs with an accusatory finger pointed at her and Stan as they embraced under the dim light on the front porch of Stan's refurbished Victorian. Despite the passage of two years of his life and the benefit of psychiatric expertise whenever he talked to himself, Leonardo continued to reel from this event, like a pebble exploded into space by the Big Bang who wants to go home.

He purred along the open road, happy for another chance to pick at it and play with it, and dream up screwball ways to reverse engineer it, like she didn't really mean it, like she really still loved him, like she might come to her senses and come back tonight. Or tomorrow night. He continued to wish for her as if she were the only one, and he couldn't, or wouldn't, or didn't know how to stop wishing no matter how many times she kicked him in the head, no matter how many golf lessons he took. He was a purist. A raging, aging, abandoned purist.

Otherwise he was fine. He liked to think.

Fine and fully recovered. Fully, definitely, one hundred and ten percent recovered. Bats back in the belfry. Intrusive thoughts quiet and comfortable in the corner. He called Mark Seltz, his divorce lawyer, from his car phone. “Mark,” he said after brief preliminaries, “what do you know about securities law?”

“What about it?” Seltz replied.

“Trading on inside information.”

“Oooh. What are the facts?”

“No facts, just a theoretical question.”

“I see. Like in case it comes up at a cocktail party⦔

“Right.”

“Well, my theoretical answer is that it's punishable by disgorgement of ill-gotten gains and jail.”

“But what is it?”

“What it is is that if you have non-public information about a publicly traded company, and you trade on that information. Like say you work at a drug company and you find out about good test results on a new wonder drug to cure cancer, and you and your brother-in-law, and the guys in your poker game, and maybe your lawyer happen to buy a few thousand shares before the test result is made public.”

“That would be bad?”

“Bad.”

“How would they find out?”

“That's not the question.”

Goddamned lawyers. Leonardo didn't see the business end of a lawyer for the first forty or so years of his life, excluding the guy who represented the bank which gave lovebirds Leonardo and Barbara the joint and several mortgage on their suburban love nest with attached office, and the guy who picked over the bones of his parents' estate, and his brother-in-law Hal, married to his older sister Gayle, whom he once hired to collect some delinquent accounts and never saw dime one on, and a few others who emerged from the shadows now and then armed with their briefcases and poker faces and dry threats of further action in the event such and such wasn't done, usually waving a pen in your eye like if you didn't do what they wanted they'd find a piece of paper and start writing, and then you'd really be sorry.

What a bunch of clowns

, Leonardo thought.

What kind of anal asshole would become a lawyer?

he liked to ask lawyers at cocktail parties, not that he was invited to that many cocktail parties.

But recently, to wit the divorce, including without limitation the divorce, or however else they would say it to cover and/or preserve their loopholes, the lawyers in and near his life were multiplying, assuming positions of leadership and responsibility, standing at turns in the road, directing traffic. Like he exited the highway and followed Brockleman's lawyerly directions around the bend to the right, came to a complete stop at the flashing red light, and turned onto DeltaTek Drive, a half-mile, two-lane strip through thick woods ending at the seven-story, glass-walled DeltaTek building, which was circled by parking lots and naturalistic plantings, and seemed calm and ominously normal. Like any other corporate day.

He paused at the little security house. A uniformed guard stepped out, gave him an eyeball, and waved him through. “Awfully normal,” Leonardo thought. He parked in a visitor spot near the front door. As he climbed out of his car he was approached by a thickly-built, neatly-dressed man carrying a walkie-talkie, with a picture identification badge hanging from his neck.

“Dr. Cook?” the man asked.

“Yes,” Leonardo answered.

“Welcome to DeltaTek. I'm Johnny Angelo. Attorney Brockleman asked me to greet you and escort you upstairs.”

“Thank you.”

“That's a nice car you have.”

“Thank you again.”