Louis S. Warren (74 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

We must be wary of reading too much into those stories. Many of them were planted by John Burke, Cody's longtime press agent and every journalist's best friend, who sat with press delegations telling stories and amusing anecdotes and the history of the show for hours on end, day after day. Sometimes Burke concocted new stories; other times he encouraged journalists to recycle other writers' material. Sometimes correspondents came up with original stories (which Burke then read and, if he liked, trumpeted as his own). His blustery, jovial narratives inspired miles of newspaper columns, which transmitted the show's messages to the hinterlands. These accounts were the dominant mode of understanding Buffalo Bill's Wild West even for people who only got to spend one afternoon with Cody and his massive entourage, and for those who never saw it at all.

Much press commentary focused, as it always had, on the savage and semisavage Wild Westerners and their encounters with the city. Indians, gauchos, “Riffian Moors,” and cowboys ventured to schools, newspaper offices, and other modern venues, always in awe, in recurring expression of the civilizing virtues of the city, and the wide-eyed wonder of rustics at the fast pace of urban progress.

59

But by 1894, more than in previous years, the show camp itself was the main attraction. Show tickets and other publicity encouraged spectators to arrive up to two hours early and tour the bizarrely placid settlement which was no mere agglomeration of people, but a living representation of progress, against which audiences could measure the historical, social, and political advancement and meaning of their own communities.

60

Here they could see buffalo, Indians, cowboys, and perhaps meet Annie Oakley or any of the other leading lights of the show.

In 1894, Buffalo Bill's Wild West had (or claimed to have) a population of 680 people, including performers and support staff. Journalists called it “a little tented city.”

61

Some called it “the White City,” as if the World's Columbian Exposition's moral messages about the supremacy of American civilization and its greater destiny were now conveyed by the Wild West show.

62

Indeed, Buffalo Bill's frontier simulacrum seemed to anticipate the modern city at least as much it recalled the vanished frontier. In London, in 1892, Frederic Remington mused on the meaning of the Wild West camp for modern urbanites. “As you walk through the camp you see a Mexican, an Ogallala, and a âgaucho' swapping lies and cigarettes while you reflect on the size of the earth.”

63

The catalogue of disparate races, thrown together in one place, implied violence and primitivismâbut it also echoed a standard device of writers seeking to convey the racial anarchy of the modern city. The reformer Jacob Riis published his photographic exposé of immigrant ghettoes, How the Other Half Lives, in 1890, the very year the U.S. Census Bureau declared the frontier closed. He spoke of the tenementsâ“where all influences make for evil”âas a kind of replacement frontier.

64

(Indeed, Riis himself was an immigrant from Denmark, and such a fan of James Fenimore Cooper that when he arrived in America in 1870, he strapped a giant navy revolver to the outside of his coatâà la Hickokâand sauntered up Broadway, expecting to find “buffaloes and red Indians charging up and down.”)

65

In lower Manhattan, he wrote, one could find “an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony . . . The only thing you shall vainly ask for in the chief city of America is a distinctively American community.”

66

When Riis searched for a “distinctively American community,” he meant a neighborhood of English-speaking, native-born Americans. Cody's “little, tented city” was not that. But, as Amy Leslie and other critics had observed at the World's Columbian Exposition, it represented, for all its racial primitivism, a kind of ideal American community: a spectacle of racial anarchy wrought into progressive order by American frontier genius.

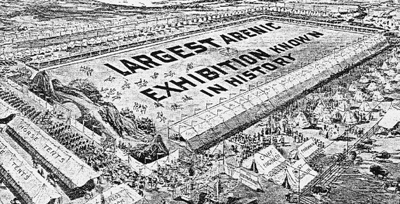

“The Little Tented City.” The Wild West camp became the premier attraction of the show, tantalizing visitors with a view of America, its frontier

past, and its technological, professionally managed future. Note the electric

generator in the foreground, not far from the buffalo pen, suggesting the

fusion of nature and technology in Cody's entertainment. Buffalo Bill's Wild

West

1898

Courier, author's collection.

The Wild West camp consisted of rows of tents along paved streets and cinder walkways between and among flower beds and small gardens, and to tour it was to contemplate both the frontier past and the urban future.

67

The disparities between Indian tipis and the modern amenities of Cody's tentâ “the size of a small farm house,” and divided into rooms, according to one reviewerâwere themselves a lesson in the material advantages of civilization and progress. In Cody's tent, “we see a telephone, curtains, bric-a-brac, carpets, pictures, desks, lounges, easy chairs, an ornate buffet, refrigerator, and all the furnishings of a cozy home.” By contrast, in a tipi standing nearby “we see a circular board floor (it should be dirt) within a ring of canvas. On a sheet of metal are the smouldering embers of a fire that makes a tepee at once a home and a chimney.” To visit first one and then the other “is to be able to compare the quarters of a modern general with the refuge of a Celtic outlaw in the seventeenth century. By just so much have we advanced; by just so much has the Indian stood still.”

68

But there was more than frontier history on display. The construction work required by the show was touted as an achievement and spectacle in its own right, a display of the show's ability to transform the city.

In 1894, the camp's transformation of south Brooklyn also conveyed important messages about the show camp's civilizing mission. “The interior of the grounds was a surprise,” wrote one visitor, “for on the large plot of waste land there has been laid out a beautiful summer park, with trees, shrubbery, flowers, and beautiful paths.”

69

At various times, the Wild West appeared not only near but

in

gardens, as in its appearance at London's International Horticultural Exhibition in 1892. Although modern readers might find the pairing of broncos and buttercups an odd contrast, in the late nineteenth century they were bookends for the story of civilization, which began in savage nature and culminated in the garden. Proximity of show to gardens echoed its domestic culmination, the salvation of the settler's cabin and the replacement of the wilderness with the pastoral, and for this reason, landscape gardening was a major activity amid show tents and tipis.

The mix of urban and pastoral at Ambrose Park resembled what many urbanites desired for their own exploding industrial cities. New York's reformers often pointed to the city's lack of parks and greenery as a source of social degeneracy. According to Jacob Riis, the common street urchin, that “rough young savage” who so terrified civil society, became a sweet-natured child in the presence of flowers. “I have seen an armful of daisies keep the peace of a block better than the policeman and his club, seen instincts awaken under their gentle appeal, whose very existence the soil in which they grew made seem a mockery.”

70

Park landscapes and urban gardens, like New York's Central Park, helped soothe the city's rough modernity. So journalists exulted that “Buffalo Bill's Wild West Company has made a garden spot where a few months ago was the dumping ground of South Brooklyn.”

71

Where the Wild West show portrayed the settling of the hostile western frontier, the camp's balance of Artifice and Nature symbolically “settled” the darker edges of the city.

The bucolic landscaping was a powerful contrast to the supposedly simmering violence of Wild Westerners, which press agents constantly highlighted. Managing Buffalo Bill's Wild West was nothing like “the management of a light-opera company on the road,” for “the people of the Wild West show . . . are all schooled in the theory that it is the proper thing to run a ten-inch knife into the anatomy of anyone who does not agree with âtheir particular whim,' ” wrote Frederic Remington.

72

Given these popular fixations, we might expect that the show's large, multiracial cast would foment anxieties about social disorder. But for the most part, the show's violence did not concern social critics except for its alleged effects on small boys. The boy who sees the show “wakes up the family by uttering weird coyote yells in his sleep. He lassoes a bedpost and the family cat, and fires a toy pistol at imaginary objects while riding the back fence at full speed.”

73

The Gilded Age middle class saw rough outdoor play as contributing to the development of manly, entrepreneurial characteristics like social aggression and risk taking, and as protection against “overcivilization.” In any case, the violence of middle-class boys was constrained by the watchful authority of parents and family, so such influences were largely construed as positive.

74

Indeed, in the minds of many, the ways that Buffalo Bill's Wild West incited such childhood play helped to naturalize urban neighborhoods through an old American ritual: playing Indian. Many reporters echoed the one who described numerous “Indian tribes” of seven-year-old boys along Brooklyn's upper Seventh Avenue. Here, clotheslines had disappeared as boys made them into lassoes for roping little girls, the trolley became “the Deadwood Stage,” and Tiger Claws, Bounding Elks, Scar-on-Necks, Black Bears, Howling Antelopes, Bounding Eagles, “and other Lilliputian savages” rampaged mischievously through the streets.

75

By inspiring such frolicsome “Indianness,” Buffalo Bill's Wild West show assisted in the transformation of city children into adults who retained frontier virtues.

76

Beyond its impact on boys, the show's seamless performance and generally law-abiding cast provided a spectacle of urban order to audiences concerned about the social chaos of their own city. The contradictions between the primitivism on display and the modern science and technology which made it safe and accessible for audiences created a tension that was dramatic and fascinating in its own right, and a constant feature of press coverage. For most of its life, the Wild West show, like circuses and other large traveling amusements, moved about by rail. During the 1890s, Buffalo Bill's Wild West required three trains to move cast, animals, support staff, and props. In addition to its hundreds of Indians, cowboys, gauchos, Cossacks, vaqueros, European cavalrymen, and other performers, the show employed ranks of skilled and unskilled laborers. Everywhere the Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders went, they brought along wheelwrights, harnessmakers, blacksmiths, ticket sellers, watchmen, butchers, cooks, pastry cooks, wood choppers, porters (to tend employees on the trains), drivers (to transport cast members and other workers from train to showgrounds and back again), canvasmen, and stake drivers, among others. All told, the Wild West show required almost 23,000 yards of canvas and twenty miles of rope.

77

Correspondents at home and abroad seemed never to tire of watching crews load and unload the cars, which was a popular diversion and a means of thinking about the show as a modern organization, as hundreds of men raced back and forth unloading materials and animals, erecting tents, stabling horses, and installing the traveling kitchen in a whir of precision that evoked nothing so much as a factory.

78

Newspapers extolled the wonders of Wild West show mobility during the 1880s, and after 1894, as the show went on the road for one- and two-night stands in towns across the country, its spectacle of a community-on-the-move became a major attraction again.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn and at other long stands, public attention to the camp's technology, social engineering, and scientific management underscored the modern relevance of a show featuring pre-modern conflict. A few examples make the point. Hoping to avert the harrowing losses from disease which plagued the camp during the European tours, Cody and Salsbury ordered vaccinations of the show cast in Brooklyn, making the Wild West camp a model of modern public health for some observers. “Cleanliness and perfect order are two cast-iron rules in Buffalo Bill's Wild West camp,” wrote a reporter on the visit by doctors from the Brooklyn Health Department to administer the “cosmopolitan vaccinating bee.”

Columnists lionized Buffalo Bill Cody and Nate Salsbury for this scientific attention to public and employee welfare. But just as significant, the response of the show's cast to the vaccinations provided lessons for the larger city. Although the Indians were “so full-blooded that the least scratch will cause a profuse flow,” they submitted willingly. Cossacks, gauchos, cowboys, and “half a dozen Arabs, and as many beautiful Arabian women, negro cooks, and helpers” also went calmly to the needle. The bravado, or at least acquiescence, of the Rough Rider camp stood in sharp contrast to the response of Brooklyn's immigrant neighborhoods in recent vaccination campaigns. During various public health alerts, authorities in greater New York attempted to vaccinate whole neighborhoods. Immigrants distrusted both vaccination and city authorities, and their response was not always cooperative. In Williamsburgh, Brooklyn's large German neighborhood, immigrants hurled “hot water and âcuss' words” at doctors who tried to vaccinate them.