Louis S. Warren (53 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

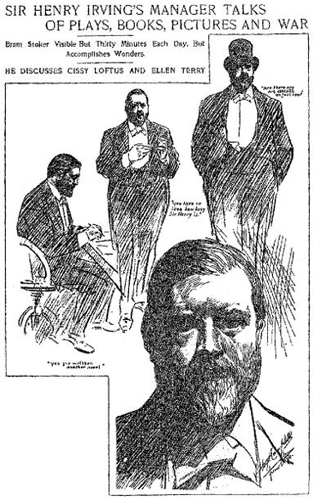

Cartoonists lampooned “The Two Great

Western Showmen,” Buffalo Bill Cody

and England's leading stage actor, Henry

Irving. From

Illustrated Bits,

May

21,

1887.

It is a singular story in other ways. In a genre characterized by frontier heroes who save white womanhood from the clutches of wilderness savageryâwild animals, Indians, and banditsâEsse falls in love with Grizzly Dick after

she

saves

him

from a bear. He is oblivious to her affections, and she pines away for him, growing weak and deathly pale after her return to San Francisco. Her salvation arrives in the form of a strapping English artist named Reginald (he might as well have been called Bram; Stoker was proud of his physique, and his athleticism) who becomes her new love interest and her fiancé. Her health returns as she forgets all about Dick.

The climax comes when Dick, through a miscommunication, receives an invitation to Esse's party in San Francisco. Dick abandons his buckskin for silk. He arrives a fop, his hair professionally curled beyond recognition, desperately trying to fit himself into urban society. He makes the transition from frontier to high society, like Cody did, but does what Cody would not: adopt the dress of his social betters. He has become a fool. Insulted by snobby guests, he pulls his bowie knife. Then, humiliated at his loss of control and horrified that he has drawn a weapon in the company of ladies, he hurls the knife to the ground, where the blade plunges into the floorboards. None of the men present is strong enough to remove itâexcept for Reginald, who presents it to Grizzly Dick as a gesture of friendship. In the ambivalent ending, Dick is persuaded to put his old clothes on, and he returns to the wilderness, while Esse and Reginald are left happily to marry.

If the novel is a flirtation with the American frontier, it also suggests the frontier is best left alone, and frontiersmen best left out there. In this light romance, it is the English artist-gentleman, Reginald, who embodies the right balance of manly power and gentility. The frontiersman is comical when he is not dangerous, and perhaps his greatest threat is the unreasoning, extreme infatuation he inspires in English womanhood, which causes Esse to wane before she is rescued by the cultured, manly, and very English hero. In fact, Esse's maladyâher pallor, her listlessness, her loss of weight, her increasing detachment, and her inability to think about anything other than the mountain manâmimics the one that strikes the doomed Lucy Westenra after her visit from a frontier hunter who provokes an all-consuming passion in Stoker's next, and most famous, novel.

93

Bram Stoker,

1901.

The North American

(Philadelphia), November

21, 1901.

The Shoulder of Shasta

appeared in October of 1895. Less than two years later, the same publisher issued

Dracula,

the novel Stoker had been crafting for seven years.

94

It was by far his most ambitious work. In his fiction, Stoker had been exploring questions about frontiers and borders for the previous four years. But, speculating on the origins of

Dracula,

we could do worse than to revisit that coaching party in 1887. It was summer, the coach path winding through the trees. The spontaneous cheers for the men on the box must have seemed as natural as the setting, and perhaps made Stoker ponderâas he often didâthe sources of celebrity and its dark power. Perhaps the impromptu performance of these divergent geniuses side by sideâCody in all his unassuming genuineness and Irving in all his imperious assumptionsâgerminated in Stoker the seed of his Dracula tale. To be sure, the powerful tension between the virtuous frontier hero and the decadent life-draining monster would occupy center stage in his novel.

Stoker's description of “Grizzly Dick” matched this famous

photograph of Buffalo Bill in London,

1887.

Courtesy Buffalo

Bill Historical Center.

Of course, the ease with which the Wild West show appealed to English racial fears owes something to the way Cody conceived it as a response to analogous American anxieties.

95

As we have seen, in Cody's hands, the frontier became the setting for a constant race contest, a crucible of American whiteness, where the destiny of Anglo-Saxon America was shored up against the implicit decay of the cities, the Industrial Revolution, new immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and a host of other ill-defined threats and pervasive cultural fears.

96

In making the social Darwinist contest between races the center of American and world history, Buffalo Bill's Wild West discounted and elided issues of class conflict. “Custer's Last Rally” was not performed in London in 1887. Instead, audiences saw the usual climactic scene, the “Attack on the Settler's Cabin.”

97

By making the salvation of the home its paramount message, the show implied that racial propagationâitself the sign of racial vigorâwould go to those who secured the frontier for their families. Burgeoning class tensions in industrial cities, such as London, could be glossed over by an appeal to a mythic natural past of racial conflict in which class simply did not figure.

Cody's centaur and indeed his company of “Transatlantic Centaurs” were but the latest of many monsters, real and imagined, and mostly malevolent, to invade London in the 1880s. In 1885, two years before the Wild West show made its debut, William Stead caused a major political and social scandal by publishing his

Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,

an exposé of child prostitution in London in which he depicted the bestial sexuality of the professional class as a minotaur. In 1886, Robert Louis Stevenson electrified the literary world with his portrayal of a doctor caught between his longing for knowledge and his bodily lust in

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr.

Hyde.

In 1888, the year after Cody's departure, mutilated bodies of prostitutes marked the trail of Jack the Ripper, and newspaper coverage of the murders served as a powerful reminder to London women of the dangers of public life, and the supposed safety of the home. Indeed, coverage of the Ripper murders resonated with the imagery of Cody's own “Attack on the Settler's Cabin,” wherein a woman is saved from certain debasement only by the shelter of her home and the courage of armed white men.

98

Cody's centaur was a harbinger of epochal shifts, paralleling his millennial messages in the United States with promises of the triumph of Anglo-American culture, the glories of Western imperial power, and the rebirth of the race in a tide of frontier bloodshed. English enthusiasm for the Wild West show stemmed in no small measure from its depiction of an English diaspora racially resurrected by the frontier. In this sense, the show's success expressed a gathering transatlantic conviction that the English and the Americans were part of a shared “race empire” of Anglo-Saxon expansion. Historians have explored connections between the Wild West show and the frontier thesis of Frederick Jackson Turner, but Turner's essay would not even be published for six more years. Cody's extravaganza is more obviously connected to Anglo-Saxonism, which was the most popular historical explanation for America's frontier success in the 1880s. Anglo-Saxonists conflated race and culture, so that the origins of liberal democracy, constitutional monarchy, representative government, and most other venerable English and American traditions were derived from racial characteristics of ancient tribesâAngles, Saxons, Jutes, and Vikingsâformed under oak trees in the German forests. According to the theory, these racial attributes hardened in battle with racial inferiorsâRomans, Picts, and Celtsâduring a long process of westward expansion, and were cultivated and preserved from continental decadence in the western bastion of the British Isles and, later, in the United States. By 1887, enthusiasm for such notions had reached near-hysterical proportions. Theories about the common Germanic origins of British and Anglo-American culture and institutions dominated historical writing and reverberated in packed lecture halls on both sides of the Atlantic. At the opening of the American Exhibition, just before Buffalo Bill's Wild West kicked off its first London performance, Archbishop Farrar prayed “fervently” for the “further development of the two Leviathans of the English-speaking race.”

99

To most observers in Britain, the Wild West show was a dramatic reenactment of Anglo-Saxon triumph.

100

Anglo-Saxonism was, of course, a variant of Aryanism, which was itself a theory of westering race history, in which Germanic peoples, Teutons, themselves originated on the high plateaus of Asia, as Aryans, who migrated west over millennia. The variations and contradictions of Aryanism did not preclude its appeal, also on both sides of the Atlantic. Americans, from Walt Whitman to General Arthur McArthur, endorsed it as history.

101

In Britain, in the very summer that Buffalo Bill's show received rave reviews in London newspapers, the Aryan myth was still proving useful as a rationale for empire in India, with columnists reinscribing the now-hoary notion that the Raj constituted England's return to the land of her Asian origins, “charged with conveying Western ideas to the race from whom our civilization came.”

102

Bram Stoker turned to Aryanists for crucial background details of Count Dracula's origins. And

Dracula,

like many of his other novels, was informed by a popular Anglo-Saxonist tradition that British and Americans were descended from ancient Viking raiders, the berserkers.

103

These invocations of mythic race history suggested connections to the American frontier myth; Aryanism and Anglo-Saxonism were coeval with the development of American frontier mythology, and in many respects they were its relatives. In all these myths, the racial energies of white people aged in the East and were renewed through bloody encounters with barbarians in the West.

104

The tale of Aryans passing from Asia to Europe and in the process becoming Britons was as analogous as it was prefatory to the story of Britons migrating west and becoming Americans.

In this sense, Indians in the Wild West show could be seen as at least symbolic stand-ins for Britain's own “savage” opponents, particularly the Irish. In 1887, the United Kingdom was beset by political controversy over the question of Irish home ruleâGladstone's signature political issueâand the threat of Irish revolutionaries. Two days after her introduction to Red Shirt and the Lakota babies at Earl's Court, Queen Victoria traveled to London's East End for another official function. Large cheering crowds lined the route, but “what rather damped the effect,” the queen wrote that night in her journal, were the small number of people “booing and hooting . . . all along the route . . . probably Socialists and the worst Irish.” But “considering the masses of Socialists of all nationalities, and low bad Irish, who abound in London,” she judged the outing a success.

105

Visitors to the Wild West camp invoked comparisons between the most primitive westerners and Britons. One London cartoonist imagined an Irish woman, a “Hibernian matron,” latching on to an Indian in the Wild West camp as she mistakes him for her runaway husband. “I found ye out at last, Tim, ye blagyard, after lavin' me an' yer five childher to the waves iv the worruld. Little I thought iv findin' ye hereâgoin' about like an ould turkey-cock wid yer tail an' feathers.”

106

But as much as Buffalo Bill's Wild West show seemed to resonate with British myths of race origin and race strength, as much as it could be a symbolic crutch for British imperialism, it was simultaneously troubling for audiences concerned about racial decay. On the one hand, the show enhanced the sense of racial kinship between the United States and Great Britain, so that

The Times,

for example, could intone on the day of its departure, “The Americans and the English are of one stock.” In this vein, columnists suggested that English manhood could take lessons from Cody's cowboys.

107