Louis S. Warren (38 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

And yet, for all its successes, the Wild West show was a volatile combination of personalities and performance whose future was by no means secure. Carver, the self-styled “Evil Spirit of the Plains,” could be a fine marksman, but he was a third-rate performer. His shooting was uneven, his temper bad. After missing a series of targets one afternoon, he broke his rifle across his horse's ears and struck an assistant.

77

Such open demonstrations of violence and cruelty were never going to be acceptable in any public entertainment, let alone the family attraction that Cody was trying to build.

On top of the threat of violence, Cody, Carver, and their cowboys drank hard all summer. Many performed badly or missed shows altogether. Later accounts claimed that an entire car of the show train was reserved for liquor. “It was an eternal gamble, as to whether the show would exist from one day to the next, not because of a lack of money but simply through the absence of human endurance necessary to stay awake twenty hours out of twenty-four, that the birth of a new amusement enterprise might be properly celebrated.”

78

What accounts for the management failures of Cody, a stage veteran who over the course of a decade in show business had mastered theatrical presentation and the demands of running his own stage company? Although he admitted to heavy drinking at times, he could be tediously pious on the subject of alcohol and performance. “In this business a man must be perfectly reliable and sober,” he lectured a wayward associate in 1879.

79

Why did he fail to follow his own advice at the outset of his new venture?

Partly, his missteps in the summer of 1883 reflected his limitations as a manager. He always had been more performer than manager, but the distinction between these talents became more visible as the size of his cast grew. Where he had directed and organized groups of up to two dozen stage players in the 1870s, now he was responsible for dozens of people, props, animals, and all of their transportation arrangements.

In facing this daunting task, he cannot have been helped by the prospective unraveling of his family. In 1882, he filed suit against a cousin for appropriating and selling a Cody family property that had belonged to his grandfather, the father of Isaac Cody. Since the parcel was in downtown Cleveland, it was worth a great deal of money, and for a time Cody and his sisters anticipated a windfall of fifteen million dollars. They endured legal setbacks throughout 1883, finally losing the caseâand all the money William Cody had invested in itâin 1884.

80

As his new show wobbled and his lawsuit waned, William Cody's marriage spiraled downward. Louisa Cody resented his show career almost from the beginning. According to William Cody's later testimony, she objected to actresses and the mores of the stage. He claimed that she witnessed him kissing his troupe's actresses goodbye at the end of a season, and her subsequent jealousy throughout his stage career kept him “very much riled up . . . In fact it was a kind of a cat and dog's life all along the whole trail.”

81

The marital tensions, and the death of little Kit Carson Cody in 1876, may have contributed to her decision, in 1878, to move back to North Platte, away from his stage circuits, which took him through Rochester. He gave her $3,500 to move there, and sent money to support her thereafter.

82

In 1882, as he prepared for his new show of western pioneering, he also publicly reinscribed the show's myth of advancing civilization back into his own life. Out in Nebraska, he built up his North Platte ranch, “Scout's Rest,” for public admiration as much as private enjoyment. He expanded his holdings to four thousand acres. The estate supported hundreds of cattle and horses, and an elegant Victorian home, with irrigation ditches, tree plantings, and alfalfa fields. The Cody home in town had been a local tourist attraction before. Now, at the newly expanded holding by the tracks of the Union Pacific railroad, Cody ordered “SCOUT'S REST” painted across the roof of his barn in letters large enough that railroad passengers could read it and recognize the home of the famous Buffalo Bill. The beautiful house and verdant fields proved his powers as domesticator of the savage frontier.

83

People who sat in his show audience might find themselves on the train, there witnessing the “real-life” frontier progress of the scout-turned-rancher-and-family-man as they crossed the Nebraska prairie.

In truth, Scout's Rest was less evidence of Cody's home life than it was artful deception. Louisa refused to live there, preferring the family home in the center of town. Even though another daughter, Irma, was born to the couple early in 1883, their mutual suspicions increased. Cody raised money for his new show and his ranch by mortgaging properties, and he was furious when Louisa refused to sign mortgage papers for the home in North Platte. He demanded the money he had sent her, and was astonished to learn she had invested in other properties, which she put in her own name. “Well, I have got out my petition for a divorce with that woman,” he told his sister Julia in September of 1883, in the middle of his first Wild West show tour. “She has tried to ruin me financially this summer,” he went on. “I could tell you lots of funny things how she has tried to put up the horse ranch and buy more property & get the deeds in her name.”

84

The divorce was halted by tragedy. In October, daughter Orra suddenly died. Cody left the show and accompanied Louisa, Arta, and Irma to Rochester, where they buried Orra next to her brother, Kit. “If it was not for the hope of heaven and again meeting there,” wrote Louisa, “my affliction would be more than I could bear.”

85

Her husband dropped his suit for divorce.

Meanwhile, between the imminent violence, the extravagant debauchery, and the seething jealousy of its principals, the Wild West show threatened to come apart. The combativeness of its stars could only weaken an entertainment based so heavily on a presentation of men from the “half-civilized” West. Popular culture had a long tradition of venerating noble savages, and in this respect there was a script for presenting Indians in ways that could appeal to audiences. But by no means were cowboys universally regarded as heroic. With wide newspaper coverage of fights between farmers and cattle ranches in Kansas, and fierce range wars across much of the Far West, the public knew “cow-boys” as rough men who seldom distinguished between herding and rustling.

Such characteristics, it seemed, were only fitting for a group that drew its members from so many races. Most cowboy gear and methods originated among Mexican herders, and what became known as “cowboy culture” emerged from a vigorous interracial exchange of droving skills, terminology, and equipment on the southern Plains. The postâCivil War cattle industry employed many black, Mexican, Mexican American, and mixed-race cowboys alongside the white and tenuously white, particularly the Irish. In 1874, Joseph McCoy, the founder of Abilene, published the first history of the cattle trade, in which he denounced cowboys for their “shiftlessness” and “lack of energy.” He held Mexican cowboys to be cruel, mean, and murderous. But even white cowboys were prime examples of frontier degeneracy, plagued by laziness and an unwillingness to leave the open spaces or even feed themselves properly (McCoy thought the absence of vegetables from their diet problematic). “No wonder the cowboy gets sallow and unhealthy, and deteriorates in manhood until often he becomes capable of any contemptible thing; no wonder he should become half civilized only, and take to whiskey with a love excelled scarcely by the barbarous Indian.” Prone to “crazy freaks, and freaks more villainous than crazy,” these “semi-civilized” brutes rendered it “not safe to be on the streets, or for that matter within a house, for the drunk cowboy would as soon shoot into a house as at anything else.”

86

Not surprisingly, the term “cow-boy” was often one of reproach, signifying someone who belonged to a lawless, itinerant, working class that, with its sensual appetites, obvious villainy, and continual threats of violence against civil order and the settler's home, too much resembled the laboring mobs of the East. In 1883, as if anticipating the great railroad strike that would grip Texas and much of the Southwest a few years later, cowboys in West Texas went on strike in the hopes of securing wages of $50 per month. This and similar efforts later in the decade all failed. But to the managerial classes, the cowboys' very act of striking seemed to justify the darker warnings about them.

87

The Wild West show made cowboys into symbols of whiteness only through a balancing act, combating their border image on the one hand and portraying them as aggressively physical and autonomous on the other. Programs distinguished Wild West show cowboys, “genuine cattle-herders of the reputable trade” from “the cow-boys' greatest foe, the thieving criminal ârustler.' ” At the same time, publicity separated “American cowboys” from “Mexican and mixed race” vaquerosâand left black cowboys out of the picture entirely. Earlier cowboy performers had begun the process of whitening to better market themselves as middle-class attractions, and Wild West show publicists made use of these efforts, notably in an 1877 article by Cody's erstwhile stage partner, Texas Jack Omohundro. The educated scion of a wealthy Virginia planter, Omohundro had been a Texas cowboy in the 1860s, and later a scout with Cody at Fort McPherson. As he broke away from Cody's stage combination in the mid-1870s, he shored up his public persona by burnishing the cowboy image in a series of articles he penned for the periodical

Spirit of the Times.

Omohundro died in 1880, but with a show full of cowboys to promote, Cody's publicist, John Burke, republished Omohundro's cowboy defense in his Wild West show programs. There audiences could read the lament of Cody's deceased friend about how “sneeringly referred to” and “little understood” cowboys were. Omohundro claimed that cowboys were “recruited largely from Eastern young men,” including “many âto the manner born.' ” Thus the mongrel, violent, degenerate range riders of many accounts became, in Omohundro's hands, adventurous, entrepreneurial, white youths who succeeded through patience, persistence, and expert horsemanship. Cowboy experience cultivated the “noblest qualities” of the “plainsman and the scout. What a school it has been for the latter!” As white men infused with rugged nature, these protoscouts were on the way to being like Buffalo Bill himself. And like him, they would soon disappear before “modern improvements” encroaching upon the “ranch itself and the cattle trade” that employed them.

88

They were the embodiment of American manhood: cultured, vigorous, naturalâand vanishing.

But for all Omohundro's attempts to elevate the social stature of cowboys, their image as frontier degenerates endured. In 1883, the American public was fully saturated with the recent, real-life bloodshed of western range wars. The Tombstone troubles launched that southwestern town's “cowboy faction” and their opponents, the Earp brothers, to national notoriety, and New Mexico's Lincoln County War saw the declaration of martial law in southern New Mexico in 1878, and the rise, demise, and apotheosis of William “Billy the Kid” Bonney by 1881.

89

The Wild West show would have to improve the cowboy's public image if it was to draw respectable audiences. Unless the chaotic energies of the Wild West cast were contained and directed, the show's short, disastrous career would become a spectacle of frontier savagery triumphant, in which drinking and carousing (followed by bankruptcy) would make it a monument only to the failures of America's most famous living frontiersman.

HOMEWARD BOUND: SALSBURY, OAKLEY, AND THE RESPECTABLE WILD WEST

Unable to resolve his many differences with his new partner, Cody was barely breaking even by the end of the summer.

90

The show's tempestuous, overly masculine cast attracted a crowd that resembled it. In late October 1883, the

Chicago Tribune

reported that five thousand people turned out to see the Wild West show, and dropped hints aplenty that the audience was not quite respectable. Although all entertainers hoped to attract as big an audience as possible, “decent” people were likely to avoid a crowd that was racially mixed. And so it was at Buffalo Bill's show, where “the crowd was a mixed one, and the newsboys and bootblacks formed a large and important element of it.” In the Wild West camp, “ferocious-looking prairie-terrors” lassoed “the ubiquitous gamin.”

91

The reviewer, in fact, seemed as preoccupied with the show's youthful, impoverished enthusiasts as with the entertainers.

They had seen the parade of the buckskin-clad heroes and painted savages, and their thoughts turned toward the interior of the yellow-covered novels and five-cent libraries through which they had waded in company with daring scouts. Their energy in selling papers and giving shines was redoubled, and one would have thought to see them all over the track that there was not a gamin in the city.

92

The reference to dime novels was a coded warning, much like the hidden clues to the disreputable crowd at Cody's theatrical performances. Newspapers and other organs of culture regularly condemned dime novels as lurid, violent inducements to crime. In the same column as the above review, the

Chicago Tribune

reported on two teenage thugs who beat and robbed two men on a streetcar, under the headline “The Dime Novel. Two of Its Heroes on Trial for Highway Robbery.”

93

The reviewer's description of a destitute army of youthful crime enthusiasts swarming to a show of prairie bad men can hardly have been reassuring for prospective middle-class customers.

Nate Salsbury saw the show in Chicago and predicted it would fail. Within days, Cody gave him the opportunity to prevent it. According to Salsbury, “Cody came to see me, and said that if I did not take hold of the show he was going to quit the whole thing. He said he was through with Carver, and that he would not go through such another summer for a hundred thousand dollars.”

94

In Salsbury, Cody sought out one of the most experienced and successful theatrical managers in the country. Born in 1845, Nathan Salsbury was an orphan by the time he was fifteen, when he joined the Union army. He fought at Chickamauga and Nashville, among other battles, and was eventually taken prisoner. After the war, he entered the stage, playing with various minstrel companies before forming his own Salsbury's Troubadors in 1874.

Beginning with this small-scale variety show of songs, dances, and comedy routines, Salsbury became a primary developer of what became known as musical comedy. Where variety performers presented unrelated routines of singing, dancing, and comedy on the same stage, Salsbury placed them together in a unified narrative, a simple play about a picnic, entitled

The

Brook.

In the course of an afternoon outing, a cast of characters ventured out on a picnic, where each character performed her or his routines, then returned home again. As one theater historian has observed, this was “hardly an earth-shaking plot,” but it nonetheless “revealed the possibility of stringing an entire evening of variety upon a thread of narrative continuity instead of presenting heterogenous acts.”

95

It was extremely popular. For twelve years, Salsbury's Troubadors toured the United States, Australia, and Great Britain, to considerable fame and a not inconsequential fortune. They earned something approaching middle-class respectability. The same newspaper that warned readers about the Wild West show also condemned the clumsy play that Salsbury's Troubadors performed in Chicago (

My

Chum,

by Fred Ward), but the reviewer's complaint was that the drama was beneath the talents of these “genial people” whose successes with

The Brook

and other comedies had fulfilled their mission of “amusing the public.”

96

Many modern readers, understandably ignorant of how Cody was inspired by his experiences on the Plains, have accepted Nate Salsbury's self-aggrandizing claim to have created all of the major attractions of the Wild West show. Salsbury's overstatement is so crude it barely requires refuting. Most of the show's enduring scenes, including the “Pony Express” and “Deadwood Stagecoach Attack,” appeared in the first season, as did various versions of the Buffalo Hunt. So, too, did demonstrations of cowboy skill, and Cody's own display of horseback shooting, not to mention the exhibition of Indian dances and combat between Indians and cowboys: all were part of the 1883 season, before Salsbury joined. Cody had been developing an entertainment based on Indians and real frontiersmenâespecially himselfâfor over a decade. Before Salsbury came along, most of the elements for a successful show were on hand.

Still, Salsbury's contribution was significant. His earlier success flowed from his ability to make narrative drama from distinct entertainments. In his hands, skits of dancing, singing, and juggling became related “acts” of a larger story, such as

The Brook.

In contrast, Cody's experience was in melodrama, a genre which came with one-size-fits-all narrative about restoration of the true woman to home and domestic bliss. His new arena presentation being in part an effort to escape the constraints of melodrama for frontier history, but it left him flailing for a new narrative structure. The Wild West was already exciting and dramatic, but its lack of clear direction was apparent in its narrative confusion, notably the absence of a suitable ending. As spectacular as the buffalo hunt was, it failed to resolve the combative drama of the earlier white-versus-Indian scenes, and therefore proved anticlimactic. Cody's efforts to rectify the situation resulted in some bloody spectacles indeed. Perhaps in an artistic expression of what it felt like to run the Wild West show during its first season, the final act of the Chicago show program for 1883 was “a grand realistic battle scene depicting the capture, torture, and death of a Scout by the savages.” This was followed by a vengeful conclusion, which veered close to the degenerative Indian hating Cody had scrupulously avoided: “The revenge, recapture of the dead body, and victory of the Cowboys and Government Scouts.”

97

Cody and Carver had an acrimonious falling-out at the end of the 1883 season, and in 1885 Cody finally won a subsequent lawsuit over who was entitled to use the name “Wild West.” Meanwhile, Salsbury had joined the Wild West show, catching up with the encampment in the spring of 1884 at St. Louis. He later recalled that he found Cody leaning against a fence in plug hat, “boiling drunk,” surrounded by “a lot of harpies called âOld Timers' who were getting as drunk as he at his expense.” According to Salsbury, Cody's spree “lasted for about four weeks,” when he became so ill “he was knocked out and had to go to bed.”

98

Salsbury's first demand was sobriety. Cody agreed. “I solemnly promise you that after this you will never see me under the influence of liquor. . . . [T]his drinking surely ends today and your pard will be himself. [A]nd be on deck all the time.” The partners demanded temperance among their employees, too, and devoted much of their publicity to the “orderliness” and sobriety of the camp.

99

Although he occasionally strayed, in future years Cody generally was sober during the show season.

100

Salsbury next applied his sharp sense of drama to Cody's alluring but incoherent assemblage. Although it is not clear when the Cowboy Band came on board, Salsbury's career had been in musical theater, and it seems likely he exerted his influence in this respect. By 1885 the show had an orchestra consisting of several dozen professional musicians dressed as cowboys. Like the bands that accompanied circuses, the Cowboy Band provided musical pacing for show acts. Beginning each show with “The Star-Spangled Banner” as an overture (although the song would not become the national anthem until 1931), their music set the mood during each act and then provided bridges between them.

101

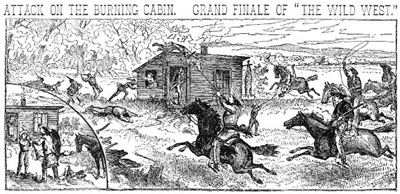

Salsbury's arrival also coincided with the addition of one new “tableau,” which would play a major role in the show's success. Beginning in 1884, and continuing almost every year through 1907, the climactic scene of Cody's show was the spectacle of a house in which a white family, sometimes a white woman and children, took refuge from mounted Indians who rode down on the building. The attackers were in turn driven off by the heroic Buffalo Bill and a cowboy entourage.

102

The “Attack on the Settler's Cabin” tapped into a set of profound cultural anxieties. For nineteenth-century audiences a home, particularly a rural “settler's” home, was imbued with much symbolic meaning.

103

The home itself presupposed the presence of a woman, particularly a wife. The home conveyed notions of womanhood, domesticity, and family. When the Indians rode down on the settler's cabin at the end of the Wild West show, they were attacking more than a building with some white people in it. To many in the audience, the piece conveyed an attack on whiteness, on family, and on domesticity itself. With its new ending, the Wild West show adapted the melodramatic rescue of the home for arena performance, allowing the cowboys and their leader, the scout (a famous melodrama star, after all) to rescue the nation's domestic unity from the threat of Indian captivity, and thereby bring the furious mobility of the showâthe constant racing of its racesâto a rest.

Middle-class people distinguished themselves from other classes partly by their emphasis on private, quiet home life, on what the historian Mary Ryan has called “entrenched domesticity.”

104

By putting home salvation and family defense at the center of the show's climax, Cody and Salsbury made their performance resonate with widespread middle-class concerns, and began the work of coaxing middle-class urbanites away from their homes long enough to see the show.

The guiding hand of Salsbury thus steadied the show combination in the 1884â85 season. Salsbury continued to appear with his Troubadors, leaving Cody to manage the show from day to day, until he and Cody could be certain the new venture would succeed. After opening in New York to great fanfare late in the summer of 1884, the Wild West show floated on steam boat down the Mississippi, playing small towns along the way. The venues were hardly suitable for so large and expensive a show, and the audiences could not cover expenses. Calamity struck when the show's boat collided with another craft. The cast and crew escaped unhurt, and they saved the Deadwood stage and the bandwagon. But the rest of the equipment was lost, along with most of the animals. In Denver, Nate Salsbury was about to appear onstage to sing a comic opera when he received a telegram: OUTFIT AT THE BOTTOM OF THE RIVER WHAT SHALL I DO. CODY. Salsbury replied: GO TO NEW ORLEANS AND OPEN ON YOUR DATE. HAVE WIRED YOU FUNDS. SALSBURY.

105

“Attack on the Settler's Cabin.” The finale of the Wild West show for most

of its years, a symbol of white family defense against threats to domestic

order and femininity. Buffalo Bill's Wild West

1885

Program, author's col

lection.

It is testament to Cody's abilities as manager that he was able to do so. Within two weeks, he had bought new livestock, including buffalo, and was showing in New Orleans. Indeed, he saw the show through its worst-ever season: forty-four days of straight rain. “The camel's back is broken,” he wailed. “We would surely have played to $2000 had it not been so ordaned [

sic

] that we should not,” he told Salsbury. “I am thoroughly discouraged. I am a damn condemned Joner,”âand, like Jonah, a curse to his partnerâ “and the sooner you get clear of me the better.”

106

But managing to retain twenty-five Indians, eight cowboys, and seven Mexicans, he saw the show through the New Orleans season.

107

Bolstered by Cody's die-hard persistence, he and Salsbury continued their effort to balance the Wild West's centaurism with domestic themes. That year, Salsbury honored a request for an audition by a lissome, diminutive woman. In no small measure, her addition to the Wild West show would contain its heaving masculinity and establish it as an enduring success. Her name was Annie Oakley.

Born Phoebe Ann Moses in Darke County, Ohio, in 1860, she was the fifth child of a twice-widowed mother. She was also a natural with guns who excelled at the common childhood practice of hunting for the family table. Indeed, the girl produced extra meat for sale to hotelkeepers. When she was fifteen, during a visit to a sister in Cincinnati, one of her customers arranged a shooting match with a traveling trick shooter named Frank Butler. The event left Butler beatenâand smitten. He and the four-foot-eleven-inch huntress married a year later. Having abandoned the surname of Moses, which she had never liked, she took the stage name Oakley. Butler became her manager, and they were practically inseparable until their deaths within three weeks of each other in 1926.

108