Lost Empire (36 page)

Authors: Clive;Grant Blackwood Cussler

“Along with his report to Dudley, Blaylock includes a coded message for Constance.” Selma flipped a page on her legal pad and traced her finger down a couple lines. “‘Having secured the

Shenandoah

, we promptly took inventory of her stores and goods. To my great surprise, in the captain’s cabin I found a most remarkable item: a statuette of a great green jeweled bird consisting of a mineral unfamiliar to me and depicting a species I have never encountered. I must admit, dear Constance, I was entranced.’”

Shenandoah

, we promptly took inventory of her stores and goods. To my great surprise, in the captain’s cabin I found a most remarkable item: a statuette of a great green jeweled bird consisting of a mineral unfamiliar to me and depicting a species I have never encountered. I must admit, dear Constance, I was entranced.’”

Sam and Remi were silent as they absorbed this. Finally Sam said, “That explains the line in his journal—the great green jeweled bird.”

“And all the bird sketches,” Remi added. “And maybe what we found in Morton’s museum in Bagamoyo. Remember all the stuffed birds hanging from the ceiling, Sam? He was obsessed. What else did he say in the letter, Selma?”

“I’m paraphrasing, but here’s the gist of it: He’s done his duty for his country, not once but twice, and he lost his wife in the process. He admits he lied to Dudley about the

Shenandoah II

’s sinking. He begs Constance’s forgiveness and tells her he intends to discover where the

Shenandoah II

’s crew found the jeweled bird and recover the rest of the treasure.”

Shenandoah II

’s sinking. He begs Constance’s forgiveness and tells her he intends to discover where the

Shenandoah II

’s crew found the jeweled bird and recover the rest of the treasure.”

“What treasure?” Sam asked. “At that point, does he have any hint there’s more to find?”

“If he did, he never jotted a word about it. At least not in plain text. Given the nature of his journal, it may all be hidden in there somewhere.”

“What about the

Shenandoah II

’s captain’s log?” Remi asked. “If Blaylock was assuming the previous crew had found the jeweled bird during their travels, the log would be a natural place to start.”

Shenandoah II

’s captain’s log?” Remi asked. “If Blaylock was assuming the previous crew had found the jeweled bird during their travels, the log would be a natural place to start.”

“He never mentions a log, but I agree with your assumption.” Sam said, “My guess: He transcribed whatever he found relevant in the captain’s log to his own journal.”

“At any rate,” Selma continued, “Blaylock continued to write Constance after the

Shenandoah II

’s capture, but his letters became more and more irrational. You can read them yourself, but it’s clear Blaylock was descending into insanity.”

Shenandoah II

’s capture, but his letters became more and more irrational. You can read them yourself, but it’s clear Blaylock was descending into insanity.”

“And those are just the plain text portions of the letters,” Pete added. “We’ve still got fourteen to decode.”

“If we’re to believe all this,” Sam said, “then Winston Blaylock probably spent the remainder of his life sailing the ocean aboard the

Shenandoah II

, scribbling in his journal, staring at his jeweled bird, and carving glyphs on the inside of the bell while looking for a treasure that may or may not have existed.”

Shenandoah II

, scribbling in his journal, staring at his jeweled bird, and carving glyphs on the inside of the bell while looking for a treasure that may or may not have existed.”

“It may be even bigger than that,” Remi said. “If the Orizaga Codex is genuine and the outrigger is what we think it is, somewhere along the way Blaylock may have stumbled onto a secret that was buried with Cortés and his Conquistadors: the true origin of the Aztecs.”

CHAPTER 37

GOLDFISH POINT,

LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA

LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA

“THERE ARE A LOT OF LOOSE ENDS HERE,” SAM POINTED OUT. HE grabbed a nearby legal pad and pen and began writing:

• How/when did Morton obtain Blaylock’s journal, his walking staff, and the Orizaga Codex?

• How/when did the

Shenandoah

’s bell end up buried off the coast of Chumbe Island? How did the clapper come off?

Shenandoah

’s bell end up buried off the coast of Chumbe Island? How did the clapper come off?

Sam stopped writing. “What else?” he asked. Remi gestured for the pad, and he slid it over to her. She wrote:

• How much do Rivera and his employer know about Blaylock? How did they get involved? What are they after?

• How did Rivera know about Madagascar?

She slid the pad back to Sam, who said, “I have an idea about one of these . . . What are they after? We suspect Rivera works for the Mexican government, correct?”

“It’s a safe bet.”

“We also know the current administration, President Garza’s Mexica Tenochca, came into office on a wave of ultranationalism—pride in Mexico’s true, precolonial heritage and so forth. We also know Rivera and his goons all have Nahuatl-Aztec names, along with most of Mexica Tenochca’s leaders and cabinet members. The ‘Aztec Groundswell,’ as the press called it, won them the election.”

Sam looked around the group and got nods in return.

“What if whoever Rivera works for knows the truth about the Aztecs? What if they knew long before the election?”

Remi said, “We did find what might be nine tourist murders in seven years in Zanzibar. If our hunch about them is correct, the cover-up goes back at least that far.”

Sam nodded. “If Blaylock truly found what we think he found, this could turn Mesoamerican history on its head.”

“Is that enough to kill for?” Wendy asked.

“Absolutely,” Remi replied. “If members of the current government won the election based on a lie and the truth comes to light, how long before they’re drummed out of office? Or even its leaders arrested? Imagine if after George Washington was elected America’s first president, it was proven he was a traitor. It’s a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison, but you get the idea.”

“Then, potentially, we’re talking about President Garza being directly involved in this,” Pete said.

Sam said, “He certainly has the kind of horsepower that’s been backing Rivera from the beginning. At this point, all we’ve got to go on is Blaylock’s journal and letters. My gut is telling me the answers are hidden there.”

“Where do you suggest we start?” Selma asked.

“His poem. Do you have it?”

Selma flipped pages on her pad, then recited,

In my love’s heart I pen my devotion

On Engai’s gyrare I trust my feet

From above, the earth squared

From praying hands my day is quartered, the gyrare once, twice

Words of Ancients, words of Father Algarismo

“The first two lines we already figured out—he’s talking about the bell and Fibonacci spirals. Now we just need to figure out the last four lines.”

THEY BROKE INTO GROUPS. Selma, Pete, and Wendy worked on Blaylock’s letters to Constance Ashworth, searching for any clues they may have missed, while Sam and Remi retreated to the solarium to pore over Blaylock’s journal, which Selma had loaded onto their iPads.

Side by side, they reclined on chaise lounges partially shaded by potted palms and billowing ferns. The sun streamed through the skylights and cast dappled shadows across the tiled floor.

After an hour, Sam muttered, half to himself, “Leonardo the Liar.”

“Pardon?”

“That line from Blaylock’s journal: ‘Leonardo the Liar.’ Clearly Blaylock was referring to Leonardo Fibonacci.”

“Of the sequence-and-spiral fame.”

“Right. But why did he add ‘the liar’?”

“I meant to ask what that’s all about.”

“The Fibonacci sequence wasn’t discovered by Leonardo; he simply helped spread it around Europe.”

“So he lied about the discovery?”

“No, he never claimed credit for it. And Blaylock, being a mathematician, would have known that. I’m starting to wonder if the line was meant as a reminder to himself.”

“Go on.”

“According to my research, the sequence is most often attributed to a twelfth-century Indian mathematician named Hemachandra who—surprise, surprise—also authored an epic poem entitled

Lives of Sixty-three Great Men

.”

Lives of Sixty-three Great Men

.”

“Another line from Blaylock’s journal.”

“Which was placed directly across from the Leonardo the Liar quote.”

“Certainly sounds intentional,” Remi said. “But what’s it add up to?”

“I’m not sure. I need to see that page again.”

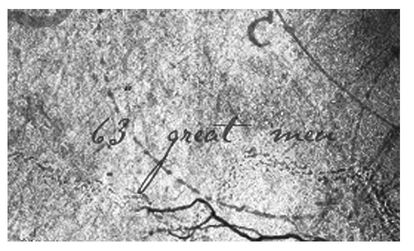

BACK IN THE WORKROOM, Sam told Wendy, “I just need to see the area around the ‘Sixty-three Great Men’ line.”

“Can do. Hold on a moment.” At one of the workstations, Wendy opened the image in Photoshop, made some adjustments, then said, “Done. It should be on your screen . . . now.”

Sam studied the image. “Can you isolate and enlarge the area around the Sixty-three?” Thirty seconds later, the new image appeared. Sam scrutinized it for a moment. “Too fuzzy. I’m mostly interested in the tiny marks above and below the Sixty-three.”

Wendy went back to work. A few minutes later Wendy said, “Try this one.”

The new image resolved on the screen:

“I had to do a little color replacement, but I’m pretty sure the marks are—”

“It’s perfect,” Sam murmured, eyes fixed on the screen.

“Care to share with the rest of the class?” Remi said.

“We’ve been assuming Blaylock used the Fibonacci spiral as some kind of encoding tool on the inside of the bell. The problem is, at what scale? The spiral’s starting grid size can be anything. That’s the piece we were missing. Now we have it.”

“Explain,” said Selma.

“Blaylock’s line about Leonardo was meant as a pointer to the ‘Sixty-three Great Men’ line. Look above and just to the right of the number three.”

“It’s a quote mark,” Wendy said.

“Or the symbol for inches,” replied Pete.

“Bingo. Now look at the dash directly below the Sixty-three. It’s a minus sign. If you move the inches symbol down and the minus sign up, you get this . . .” Sam grabbed a pad, scribbled something, and turned it around for everyone to see:

6 ˝ − 3 ˝ = 3 ˝

“Blaylock is telling us the starting square in his spiral is three inches.”

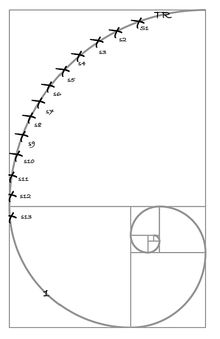

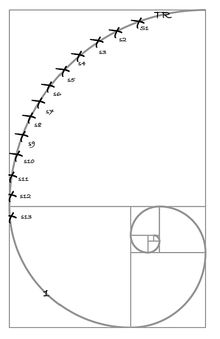

THEY QUICKLY REALIZED the mathematics needed to re-create the spiral were beyond their grasp. Blaylock had devised his bell-spiral combination based on his expertise in topology. To solve it, the Fargos needed an expert of their own, so Sam took a page from Remi’s book and called one of his former professors at Caltech. As it happened, George Milhaupt was now retired and living just seventy miles away on Mount Palomar, where he’d been playing amateur astronomer at the observatory since leaving the institute.

Sam’s brief explanation of the problem so intrigued Milhaupt that he drove immediately to La Jolla, arriving two hours after Sam’s call.

Milhaupt, a short man in his mid-seventies with a monk’s fringe of white hair, followed Sam into the work space carrying an old leather valise. Milhaupt looked around, said, “Splendid,” then shook everyone’s hands. “Where is it?” he asked. “Where is this mystery?”

Not wanting to muddy the waters, Sam restricted his briefing to the

Shenandoah

, the bell, and the relevant portions of Blaylock’s journal. When he finished, Milhaupt was silent for thirty seconds, pursing his lips and nodding thoughtfully to himself. Finally: “I can’t argue with your conclusions, Sam. You were right to call me. You were a good math student, but topology was never your strong suit. If you’ll bring me the bell, your Fibonacci calculations, and a large sketch pad, then leave me alone, I’ll lock horns with Mr. Blaylock and see what I come up with.”

Shenandoah

, the bell, and the relevant portions of Blaylock’s journal. When he finished, Milhaupt was silent for thirty seconds, pursing his lips and nodding thoughtfully to himself. Finally: “I can’t argue with your conclusions, Sam. You were right to call me. You were a good math student, but topology was never your strong suit. If you’ll bring me the bell, your Fibonacci calculations, and a large sketch pad, then leave me alone, I’ll lock horns with Mr. Blaylock and see what I come up with.”

NINETY MINUTES LATER, Milhaupt’s scratchy voice came over the house’s intercom system. “Hello . . . ? I’m done.”

Sam and Remi and the others returned to the work space. Sitting on the table, amid dividers, pencils, flexible measuring tapes, and a pad covered in scribbles, was a sketch:

Other books

Some Assembly Required by Anne Lamott, Sam Lamott

Blood & Lust: The Calling by Rain, Scarlett

2009 - Ordinary Thunderstorms by William Boyd, Prefers to remain anonymous

El consejo de hierro by China Miéville

Angeleyes - eARC by Michael Z. Williamson

Cathedral by Nelson Demille

The Fall of Hades by Jeffrey Thomas

The Stranger You Know by Jane Casey

All the Beautiful Sinners by Stephen Graham Jones

Girl Fight (Rough Lesbian Fight Sex) by Dalia Daudelin