Long Shot (61 page)

Authors: Mike Piazza,Lonnie Wheeler

On the broader scale, I fully realize that I’ve alienated plenty of people over the years. Especially in New York, where I felt an enormous amount of pressure to earn my salary, silence my critics, and carry the Mets to the playoffs, I simply wasn’t the guy who was going to come to your bake sale. Alicia thought I became a different person every time I set foot in the city—edgy, more intense. But I can’t blame it all on New York. I’ve been a brat on a fairly regular basis.

Looking back, I wish I’d been able to loosen up a little. I wish I’d had more fun playing the game. Al Leiter used to ask me, “When are you going to

enjoy

this shit?” I never really did. That’s the principal regret I have about my career. Poetically, I guess, that happens to be Mike Schmidt’s main regret, as well. He said it straight-out in an interview with Tim McCarver. Funny how that works.

In the clarity that comes with retirement, I understand that, as a player, I was too moody, too brooding, too consumed, too unlikable. I wasn’t really

interested

in being likable. I somehow felt that, if I tried to be everybody’s best friend, my guard would be down. It would betray weakness. My persona was: to hell with all this other shit; I’m here to play ball. It was an attitude that drove me. I wanted to be the Mike Schmidt that I watched from my box seat on the third-base line. I wanted to be the Ted Williams that I read so much about and met in my backyard. I wanted to be as cool as Joe DiMaggio, who, you might say, was beloved in spite of himself. Those were the guys whose style appealed to me and set a standard. Aloof, a little surly, all business. Reluctant stars. Or so it seemed.

It worked for me, but not without contradictions. For much of my career, I suppressed my spiritual side. I also made myself less approachable than I intended to. Only after the fact—the exercise of writing this book has helped, I think—have I come to terms with my desire and need to touch people. I aspire, now, not only to inspire but to be somebody you’d like to hang out and have a beer with.

I was that guy, at least to a partial extent, when I lived with Eric Karros in Manhattan Beach. Eric had it right when he said we were “just a couple of jackoff ballplayers” in those days. It was a great time in my life, and it felt like it would never end. Then came the contract negotiations. Like my summer at Vero Beach eight years before, they educated and permanently changed me.

Americans are kind of funny about athletes and contracts. We’re all for

the spirit and principles of capitalism and everyone’s opportunity to make of themselves what they will . . . but only up to a point. For some odd reason, this seems to apply more to baseball than practically any other occupation or pastime. A ballplayer exceeds the general public’s comfort level—tests its good graces—when he makes

too

much money, whatever that number is. In Los Angeles, in particular, I felt like the poster boy for that phenomenon.

Before I battled the Dodgers over dollars and terms, I was regarded, publicly, as relatively charmed and not too bad a dude, an L.A. kind of guy. By the time they traded me, though, I had, by negotiating unsentimentally—from what I perceived as a position of strength—depleted my popularity and polarized the fan base.

Even now, though, I can’t apologize for driving a hard bargain, for wanting to cash in that great big chip on my shoulder. I couldn’t suddenly lose the attitude just because it was contract time. That attitude was indispensable to what I’d become. It was my functioning baseball ego. If I’d considered myself lucky to be there, I wouldn’t have been there.

Through stubborn pride and grim single-mindedness, I was able, ultimately, to accomplish more in baseball than anyone ever thought I would; and I would find it gratifying if

that

were remembered as my contribution to the game and the culture; if the tough crowd that we’ve become could still find a place in its heart to be inspired by an old-fashioned, American-style success story.

From where I sit, that’s what mine amounts to.

My father, Vince, with his mom, Elizabeth, the daughter of Italian immigrants. Dad would take us to her house on Sunday afternoons—especially if the weather was nice—then he’d drop off my brothers and haul me out to a ball field for batting practice.

My mother, Veronica—everybody calls her Roni—was a nurse before she met my father. While Dad groomed me to hit a baseball, Mom took care of most everything else, seeing to it that I, like my brothers, was steeped in conservative Catholic values.

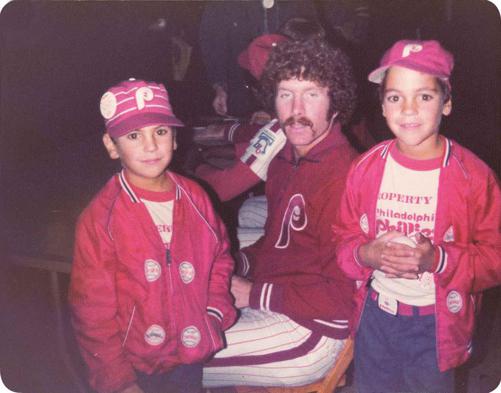

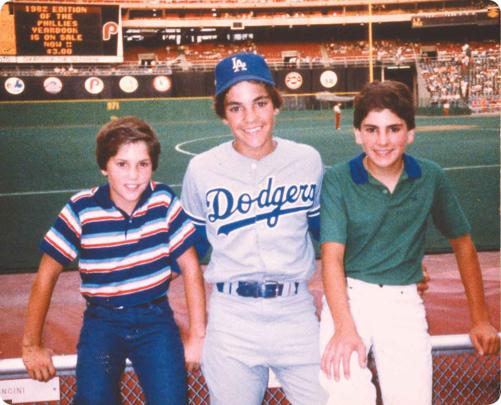

We got our season tickets at Veterans Stadium in 1976, and our seats were perfectly located along the third-base line, where I could study the movements of my hero, Mike Schmidt. He was my inspiration and role model. My brother Vince (left) and I had our picture taken with him that year on Fan Appreciation Day.

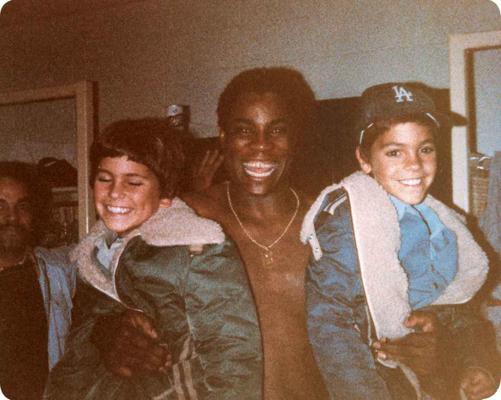

In 1977, the Dodgers clinched the National League pennant in Philadelphia. Tommy Lasorda arranged for Vince (left) and me to come down to the clubhouse for the postgame celebration. We became a part of it when Dusty Baker lifted us up to share the moment.

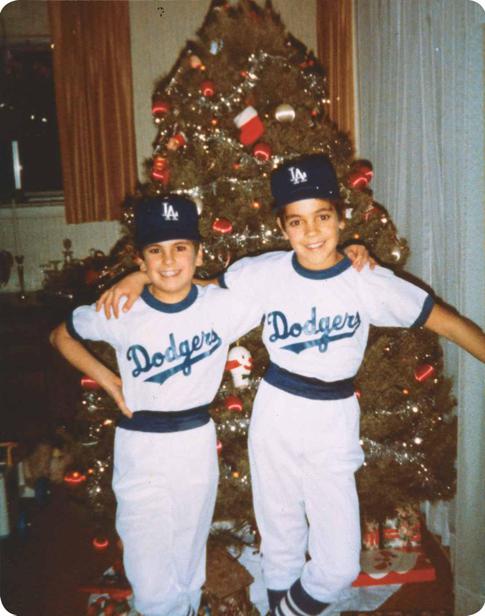

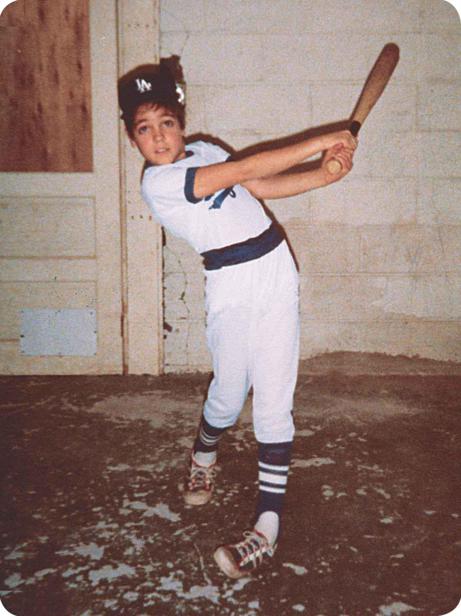

When you’re ten years old—Vince was eleven (I was always bigger)—and your dad is a good friend of Tommy Lasorda, you get a Dodger uniform for Christmas.

In the basement of our house in Phoenixville, my father propped a mattress against the wall so I could hit and throw baseballs into it. He had plenty of gimmicks, and most of them worked.

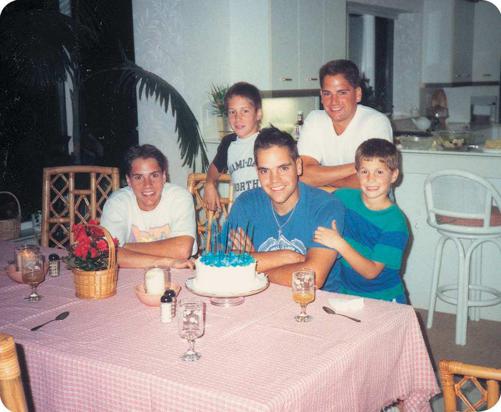

When I was twelve, I was the Dodgers’ batboy whenever they came to Veterans Stadium. My brothers Danny (left) and Vince got to hang around. I was beginning to realize the advantages that knowing Lasorda would provide me.

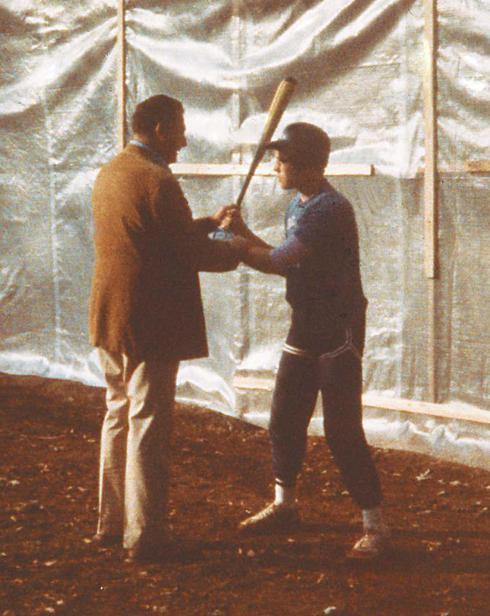

By the time I was sixteen, I was a serious student of the Ted Williams approach to hitting. I’d read his book countless times. So I felt like the luckiest kid on the planet when Williams, at the suggestion of local scout Eddie Liberatore, actually came out to our house in Phoenixville to watch me hit in the batting cage that my dad had built in the backyard. “I don’t think I hit the ball as good as he does when I was sixteen,” Williams said. “I’m not shittin’ ya.”