Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor (4 page)

Read Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor Online

Authors: Yong Kim,Suk-Young Kim

Tags: #History, #North Korea, #Torture, #Political & Military, #20th Century, #Nonfiction, #Communism

There is no doubt that the difficulties endured by the North Korean people in the 1990s were even worse in labor camps, but the famine testifies to the harrowing reality that the conditions in the labor camps and “normal” society were not that different; perhaps the variation was in the degree of hardship rather than its nature.

Ironically, it was this lethal famine that facilitated Kim’s escape across North Korea to China. As Kim tells us, the famine in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the central food distribution system collapsed, triggered a massive mobilization of starving people, forced to travel around in search of food. Whereas civilians had needed permission to travel in the past, by the time Kim escaped from the camp in 1998, the central government found it virtually impossible to prevent starving economic migrants from moving around the country, and at times, even outside the country in search of means of survival. The journey Kim Yong made across the Chinese border is typical of many North Korean economic migrants and defectors who still desperately seek asylum. Even today, an undocumented number of North Koreans, who have endured monumental suffering for the past fifteen years or so, continue to escape their homeland, often crossing the border to China taking the same risky route that Kim once followed. Kim Yong’s story is an ongoing story, and his destiny is shared by countless other Koreans.

The fate of these border crossers—estimated from under 100,000 to 400,000, according to varying sources

26

—is precarious and their future obscure at best once theyreach China. Even in the face of the international community’s persistent requests, China still does not recognize North Korean border crossers as international refugees, which poses enormous challenges for NGOs and other organizations intent on helping these North Koreans reach a safe place. Although the North Korean Human Rights Bill passed the U.S. Congress in October 2004, concrete measures to assist North Korean refugees have yet to be implemented, leaving the fate of these stateless and undocumented border crossers mostly to a few NGOs. It cannot be overemphasized that there needs to be a systematic agreement at the state level, involving international organizations, such as the United Nations Higher Commission for Refugees, to guarantee basic human rights to the increasing number of North Korean refugees in China and elsewhere before they reach a safe haven. Kim Yong was fortunate enough to fall under the protection of South Korean Christian missionaries who led him through his journey. But not all refugees are so lucky. Arguably the worst kind of disaster that can happen to North Korean border crossers in China is sexual trafficking of women. North Korean women who do not have legal status in China often find themselves forced into sexual slavery or are sold into rural families as brides for Chinese males who otherwise cannot afford to find mates.

27

The harsh fate awaiting North Korean border crossers remains underdocumented at best, and international efforts are needed to end this humanitarian crisis.

The high socialist ideals set up in the early North Korean state have degenerated into gruesome reality and erupted as crisis, to the point where the government cannot even provide the basic means for survival for its people, let alone a utopian life in a socialist paradise. This crisis by no means haunts North Korea alone—it also falls on every nation’s conscience, as human rights infringement and politico-economic migration can only be understood through a transnational scope. In this respect, while Kim Yong’s stories primarily read as a chronicle of the North Korean nation’s failure, they also capture a broader predicament with which mankind has been struggling throughout history. Only the future will tell whether such drastic failure to protect its people will lead to the downfall of the North Korean state. In the meantime, we can only fathom the depth of this national and transnational tragedy unfolding in the present tense through Kim’s haunting stories.

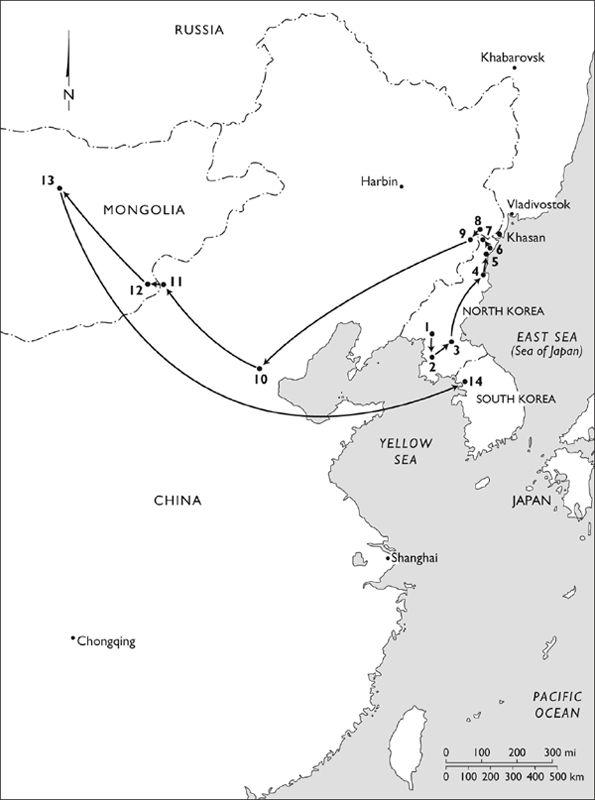

Kim Yong’s Escape Route

| 1. Bukchang | 8. Tumen |

| 2. West Pyongyang Station | 9. Yanji |

| 3. Go-on | 10. Beijing |

| 4. Cheongjin | 11. Erenhot |

| 5. Rajin | 12. Dzamïn Üüd |

| 6. Unggi | 13. Ulaanbaatar |

| 7. Namyang | 14. Seoul |

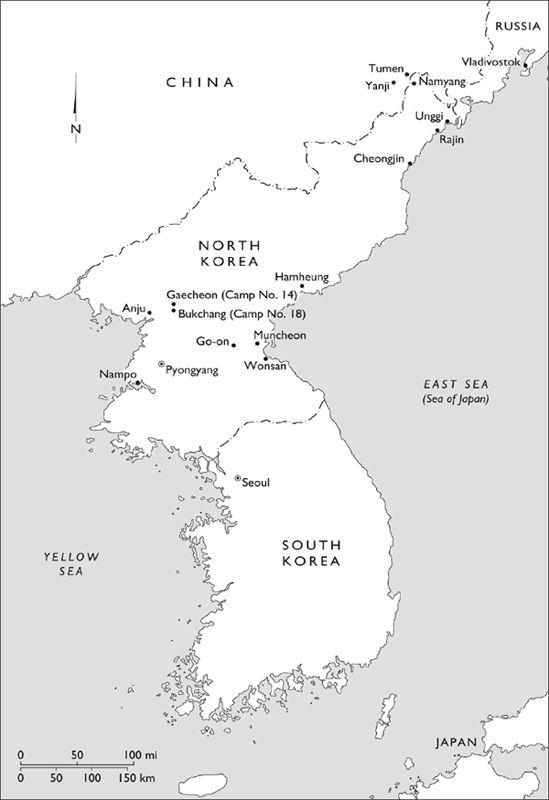

Map of Korea

Rustling waves approach the shore in endless succession, damping the tips of my toes and luring my sight back to the horizon. Beyond that horizon lies a place I once called home. But on this side of the ocean, the shoreline appears etched with motley traces of strangers. When touched by the sea, they gradually melt as if they never existed. As I watch this rhythmic but futile movement, the shores of my heart, also marred by scars of memories, wells up with longing. But just like the infinitely shattered sand cannot hold back the waves, my fragmented being cannot contain the swaying memories.

Los Angeles, California. 2008.

The sun in the sky is melting from its own brilliance.

I close my eyes to rest, but myriads of faces appear even when my eyes see nothing, soon to dissolve into obscure figures. Long-forgotten names, the faint smell of my young children, the low voice of my wife, the wind blowing from bleak mountains, slowly moving trains, an endless journey through the night … where have they all gone?

I come from thousands of miles away. I am a stranger from a strange land, a restless specter in search of shelter. I’ve crossed the river in the netherworld and seen pillars of fire in the desert. Constantly longing for home, I wander around, accompanied by a long shadow cast from afar. I call out the names of once close friends, but hear nothing in return. I whisper the names of my wife and children, but they are simply a disappearing impression or warm and brief sensation, momentarily illuminating my presence, only to leave me behind in this strange world.

I grab a handful of sand and try to feel its warmth. But only dust remains on my palms—a silent reminder of the home I left for good. This emptiness makes me think of the strangers who must be living in my old home in Pyongyang. They must be strolling in the small garden my wife once cared for, but would they be aware of the previous residents whose lives were shattered into a thousand pieces? Would I recognize my home even if I were to return?

Home is an illusion.

An incorrigible wanderer who cannot avoid recurring nightmares, I drift from shore to shore.

First Memories

But where was my home anyway?

What does my memory tell me about it?

My first home was the state-run orphanage in Pyongyang, where I grew up under the loving care of the Great Leader Kim Il-sung, the founding father of North Korea. My first dear memory about this home, however, is not associated with the Great Leader but with Kim Hye-hwa, the kind nanny who nurtured me even before I could remember. A warm, loving person, Kim Hye-hwa always had a modest but kind aura. This graceful lady had lost an infant son of my age during the Korean War, which added a tone of sadness to everything she did. I wondered whether I was the first baby orphan she took to breast-feed after the loss of her own child. Did I resemble him? I never asked, but she must have hoped to forget the dreadful void left in her when she took me in her arms.

Unlike Kim Hye-hwa, the other nannies were quite strict and severe in their treatment of orphans. Most nannies were either spinsters or widows who had lost their potential mates or husbands during the Korean War. As I recall, most of them unhappily realized that they were doomed to spend their entire life in an extended family of orphans, without male companions. They were absolutely unforgiving in punishing mischievous pranksters. Most of them were ready and willing to smack orphans when they misbehaved, or punish them by refusing to change diapers or feed them snacks. When it came to inculcating revolutionary ideology in us, however, the nannies transformed into dignified priestesses guarding the holy shrine of the living god Kim Il-sung.

The sky is blue and I feel happy,

Play the accordion out loud.

I love my homeland, everyone lives happily,

Our father, the Great Leader Kim Il-sung,

The warm embrace of our party!

The lyrics of this first song I learned to sing made me happy, and inspired hope and trust in the hearts of the neglected orphans. I remember how my little body used to shudder with delight when I sang out the words “warm embrace,” and how I longed for it every moment. Warm embrace. The party. Warm embrace. We are happy. Our Great Leader.

The nannies told us about our Great Leader’s heroic revolutionary conquests. Naturally, the first sentence I learned to write was “Thank you, Great Leader Kim Il-sung.” While listening to the revolutionary saga, we orphans were all mesmerized by his strong and handsome appearance. Accompanying this hero was the beautiful and courageous wife, Kim Jeong-suk,

1

who assisted Kim Il-sung’s revolutionary projects with unflinching courage and self-sacrifice. Looking back, never did I doubt that the Kims were invincible gods who single-handedly rescued our homeland from the Japanese colonialists and American imperialists. They presided over our daily lives, looking down at us from the portraits hanging on the walls. Kim Il-sung’s and Kim Jeong-suk’s birthdays—April 15 and December 24 respectively—were memorable holidays, as abundant food and lavish presents were sent to us by the Korean Workers’ Party (

Joseon rodongdang

). Male orphans collectively celebrated their unknown birthdays on the national mother Kim Jeong-suk’s birthday, whereas female orphans celebrated theirs on the national father Kim Il-sung’s birthday.

After the establishment of the socialist regime, the North Korean government confiscated the wealth of the landlords and capitalists and converted their properties into state facilities. The orphanage where I grew up, I was told, had been a wealthy landlord’s mansion before the founding of North Korea. However, all the extravagant traces of the feudal past were replaced by revolutionary paraphernalia. The red flag of the Korean Workers’ Party covered the walls where once must have stood panels displaying literati calligraphy; portraits of Kim Il-sung must have replaced delicate ink painting featuring flowers and butterflies on silk. I still remember that a stream flowed by the orphanage. Our nannies used it to wash everything that needed to be washed—rice, vegetables, clothes, and dirty orphans. The generous stream always provided for us without demanding anything in return. I would spend hours gazing at the water, fixated on the constant clear stream. When I stood in front of that eternal stillness in movement, the flow eventually stirred up my uneasiness and my questions, which merged with the current. I wasn’t sure where they came from and where they were headed.

Who am I?

Where do I come from?

What will my future bring?

The stream always remained silent.

Like every child in North Korea, I learned eating habits shaped by daily political rituals. Each time the nannies handed out food, they told us that it came from the Great General Kim Il-sung. We would bow deeply in front of his portrait and thank him even before touching the food. Whenever I raised my head, the Great Leader was there in the photo, generously smiling, presiding over the children who eagerly prepared to eat.