Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor (14 page)

Read Long Road Home: Testimony of a North Korean Camp Survivor Online

Authors: Yong Kim,Suk-Young Kim

Tags: #History, #North Korea, #Torture, #Political & Military, #20th Century, #Nonfiction, #Communism

Terrified, I immediately followed the command. Then a couple of guards joined him in kicking my head with rough military boots. I almost lost consciousness: the emotional toll that had weighed like death itself during the truck ride nearly drove me mad. And even before I could recover from the shock of surviving what I had thought would be my execution, I was being kicked in the head. The front of my jacket was soaked in warm blood running from my nose. With my head hanging, still kneeling on the ground, I heard the vice-director of the detention center talking to the officer at the reception area:

“The son of a bitch is an American spy. He needs to be completely reformed in your facility.”

I realized that the three and a half months of interrogation at the Maram detention center had concluded in a sentence mandating lifetime forced labor. That was not something I had anticipated, and I did not know what to make of it. I’d been certain that I would be executed that day. After the vice-director and the guards from the detention center left, the new guards threw me into a cell where I sat for a while. Without saying anything, one guard stuck in a plate on which leftover food, possibly from the guards’ meal, was thrown. Although my lips and mouth were bleeding from the kicking, I ate all of it. That turned out to be the best meal I ever had at that camp.

At 8:00 a.m. a medical doctor came in to inspect me. Then I was taken to a warehouse where I was stripped of my civilian clothes and given a prisoner’s uniform and underwear. They were made of coarse gray nylon material and smelled as if someone’s corpse had rotted away in them. After I put those on, I was put in a car that drove me up the mountain. On the way, I could see mine shafts everywhere. When the car stopped by another office area on the mountainside, I was asked my name and age and was given a two-hour orientation about how to behave myself. I was told that the prisoners could not talk to each other about anything except work-related issues; prisoners should lower their heads and hold their hands behind their backs when the guards passed by; prisoners should write self-criticisms on their former lives; prisoners should not hesitate to report to the authorities when they discovered other prisoners expressing dissatisfaction; prisoners should not climb the surrounding mountains without permission, or it would be regarded as an attempt to escape and shots would be fired promptly. Then a guard took me to a shaft and handed me over to the mining team. Even in my confused state of mind, I was utterly shocked to face the prisoners there—literally thin layers of dry skin glued to skeleton. Only their wide eyes were glittering on dark faces covered with soot as they tried not to look directly into the guard’s eyes. At the shocking sight of these half-human half-ghosts, my heart dropped. The guard shouted to them: “Here is your new team member, show him his work.” The head of the team told me that my job was to push the cart loaded with stone. Without any further instructions or explanations, I was immediately put to labor, just hours after my arrival at the camp. Thus my life began in hell, from which death was the only escape.

After two round-trips with the loaded cart, my entire body shook. All my life I was always healthy and on the sturdy side, but during the three and half months of confinement and continued torture, my physical strength had noticeably declined. When lunchtime arrived, I felt like collapsing on the ground because of hunger pangs. The leftover food I’d eaten upon arriving at the camp had long been digested. The lunch consisted of watery soup and a handful of boiled corn kernels and wheat. It was rough and tasteless. Other prisoners were voraciously eating it with rough salt they’d received in the morning. Later I learned that the salt was supposed to serve as the only means to brush our teeth. This is how my first day at the camp began. It was very clear that this was the first step in a prolonged passage to death.

Camp No. 14

In North Korea, everyone knows that a labor camp is a place where life is suspended. One does not live there, one slowly dies there. I was simply another dead soul in Camp No. 14.

At 5:00 a.m. everyone was awakened. By 6:00 a.m. the prisoners had finished their meager breakfast and marched toward the workplace. Since the mine shafts were hidden in deep valleys, nobody could see the sunlight. At 7:00 we were already busy at work. Between 12:30 and 1:00 p.m., we had a quick lunch underground in the mine shaft. In order to go to the toilet, the prisoners had to wait to form groups because there was little light and they had to share one bulb to move around. One person had to carry the lamp and lead the way. Then we came out of the shaft around 11:30 p.m. and ate supper outside in darkness. According to the rules, the work was supposed to end by 8:00 p.m., or by 9:00 p.m. at the latest. However, no guard bothered to enforce this. The only real rules in Camp No. 14 were the guards’ decisions. After work, we marched back to our barracks and stayed up another hour for political struggle consisting of mutual and self-criticism. At 1:00 a.m., three hours later than the camp regulations, everyone went to sleep. Before my arrest, I used to sleep eight hours a night, on the average. At the camp, that was cut in half.

Even by notoriously subhuman North Korean camp standards, No. 14 was the worst of them all. To my knowledge, no human being had escaped it alive. Prisoners were beyond the point of feeling hungry, so they felt constantly delirious. But what was really killing us was psychological and emotional torture. No family members were allowed to stay together. Upon arrival at the camp, husbands and wives were separated. Children were allowed to stay with their mother until they turned twelve; then they were segregated according to sex and kept in separate barracks. Once families were separated, there was no way of knowing whether other members were dead or alive. The only chance they might have to see each other was during the public executions when all prisoners were gathered in the courtyard. Other prisoners told me that the conditions in Camp No. 14 were so ghastly that in 1990, about three years before my arrival, the inmates had rebelled, killing half a dozen guards. In retaliation, jailors crammed 1,500 prisoners into an empty mine shaft and massacred them with multiple explosives. After this, the guards became even more iron-fisted, but at the same time, public executions decreased in number, replaced by secret murders. When the guards came and took away some prisoners, experienced ones knew that it might be the last time they saw those fellows. Often they did not return, and that meant that they were no longer in this hell with us.

Sixty people slept in our room, which was about 10 by 6 yards and was lit by only a couple of light bulbs. There was no furniture in the room. Even if there had been books, I doubt anyone would have had the strength to read them. When the prisoners returned from work, they simply wished they were dead. At 1:00 a.m., the guards would count the prisoners and lock them in. I can still vividly hear the squeaky sound of the rusty lock behind the closed doors. When that metallic scratching signaled the end of the day, my heart bled as if the metal lock had penetrated straight into my body. As soon as the guards closed the door, the prisoners fell to the ground and immediately went to sleep. Since there were way too many people crammed into one room, one had to lie down as fast as possible in order to secure floor space. Everyone breathed heavily, as their lungs were filled with coal dust and ash. We slept on the cement floor without any bedding, but since we were in a mining camp, there was enough coal to burn all year round, so heating was not a big problem even in midwinter. However, in the summertime, the cool cement floor was unbearably hard on the back. Prisoners were supposed to stand guard in turns and the transfer of duty to a new vigil took place every hour. It was really impossible to have a minute of privacy in Camp No. 14. In the room there was an indoor toilet made of a large metal bucket. For the first three months, I slept right next to that toilet, as did every newcomer according to the rules among prisoners. It was never completely dark after the doors were locked, as the light bulbs shone dimly. However, there were times when some prisoners slightly missed the mark and splashed shit on my hair and face.

The outdoor toilet was made of hopsacks filled with sand and piled up on top of each other. The prisoners squatted on top of the piled-up sacks. There was no such thing as toilet paper. Everyone knew how to wipe themselves with a little stick. Some privileged people who worked in the kitchens or the pigsty had the luxury of using corn silk or leaves they had collected as toilet paper. Since the mining prisoners lacked exposure to the sun necessary for their bodies to make vitamins, their skin was always dripping pus. There was no mirror in No. 14, so there was no way of seeing one’s own physical decline, but by looking at the ghastly faces of other prisoners, I could picture what kind of half-beast half-ghost I had turned into. If there had been mirrors for everyone to see their faces, that horrific sight would have been enough to drive one mad. To add an extra touch to our subhuman appearance, everyone’s hair and beard were cropped carelessly by other prisoners when the guards let us use dull scissors once a month. No razor blades were handed out in order to prevent suicide and accidents. Life at Camp No. 14 could hardly be called a human existence. Everyone was serving a lifetime sentence and immediate death seemed like an enormous blessing.

In the beginning I did not speak and tried not to hear anybody else’s words or take part in conversation. I had no curiosity about anything. For a month I did not talk to anyone, even though some approached and asked where I’d worked before ending up there. Despite my efforts to stay out of trouble, I almost got raped one night during sleeping hours. Other prisoners, including the vigilant, were in their deadly sleep. Even if they were awake, they did not have the strength to bother trying to interfere. The aggressor had been especially kind to me for a couple of days leading up to the attempted assault. He used an honorific form when talking to me and followed me everywhere I went. From the very beginning, I could sense that he was a snitcher. My experience at the National Security Agency told me so, as did my experience at the orphanage. Having barely escaped the rape by pushing him away with what little strength I had, the next day I beat him hard in the mine shaft when others were not watching. Even though I was exhausted with daily labor and poor diet, I was relatively fresh and could easily knock out any other prisoners. In response, the guards severely beat me in public for touching their collaborator. As a matter of fact, one prisoner out of three worked for the guards, observing and informing on their fellow inmates. Promises of easier work and scraps of food motivated snitching.

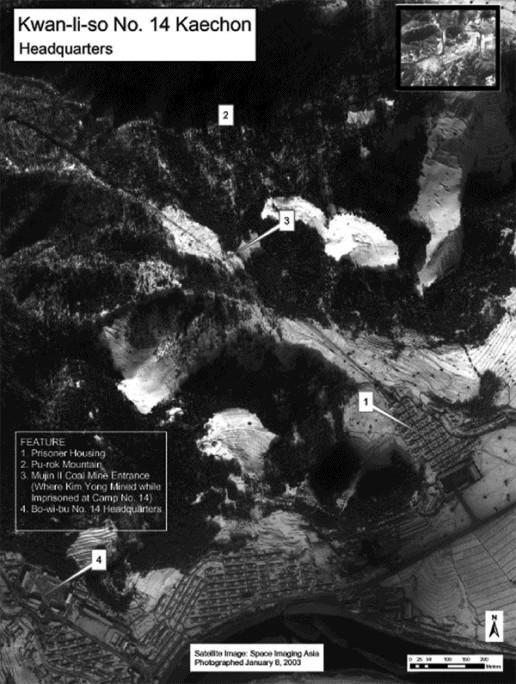

A satellite photo of Camps 14 and 18, where Kim Yong was imprisoned from 1993 to 1999.

From 1993 to 1999, I worked in mine shafts 2,400 feet below ground. It was so stifling and sultry down there that even in the middle of severe winter, the prisoners wore only underwear, and it was difficult to breathe. Every day, prisoners in my work unit would descend to collect coal along a tiny tunnel. There were no elevators; we went down in a small round metal container used to transport coal. When it was filled, another work unit would lift the container up and empty it into a train car. In the beginning, I was out of sync with the other workers in my unit, who moved like parts of the same machinery. Enfeebled as they were due to perpetual hunger, they found ways to coordinate their movement. I could not understand how they could carry on, eating so little and sleeping so little, but it seemed that everyone who had been around long enough had internalized the slow rhythm of prolonged labor. I certainly wasn’t used to that kind of work, and nobody had shown me how to dig a mine or load a container. I was always getting in someone’s way, and because of that the trailers would be lined up waiting for my portion of coal to be poured in before they could move out of the shaft. I was constantly beaten for tardiness by the merciless guards. One day in the first month after I arrived, I interrupted others as usual. Immediately a security guard showed up. Like all the other guards, he was accompanied by two soldiers with rifles.