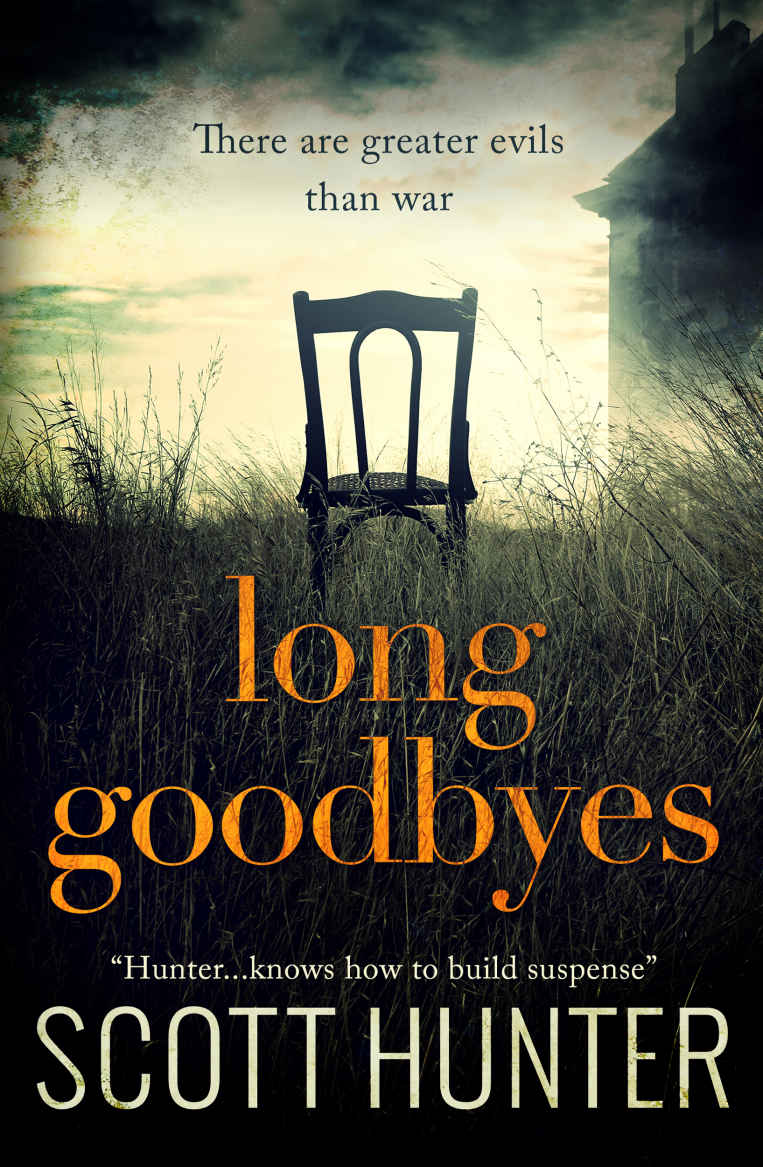

Long Goodbyes

Authors: Scott Hunter

LONG GOODBYES

Scott Hunter

...

Scott Hunter was born in Romford, Essex in 1956. He was educated at Douai School in Woolhampton, Berkshire. His writing career began after he won first prize in the Sunday Express short story competition in 1996. He currently combines writing with a parallel career as a semi-professional drummer. He lives in Berkshire with his wife and two youngest children.

A Myrtle Villa Book

Originally published in Great Britain by Myrtle Villa Publishing

All rights reserved

Copyright © Scott Hunter, Anno Domini 2015

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher

The moral right of Scott Hunter to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

In this work of fiction, the characters, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or they are used entirely fictitiously

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Andrew and Rebecca Brown (Design For Writers) for the cover design, and to my insightful editor, Louise Maskill

...

For the soldiers, sailors and airmen of the great conflict, 1914-1918

chapter one

When I close my eyes I can still picture it; dark and brooding in the twilight, a house heavy with melancholy - as if its very fabric had been soured by some dreadful, catastrophic tragedy. Even though the events I am about to describe are six years past, in my mind’s eye I can still see the grey stone blocks, the jutting angles of the asymmetrical roof, the porch with its fine marble pillars, and the five weathered steps to the front door. But there I must halt, because nothing on this earth - nothing - would induce me even to approach, let alone cross, that threshold again.

And so let me begin in Belgium, Inspector Keefe, for that is where I first met Jack. After all, it was only as a consequence of his great torment that we came to Ireland at all.

It was a terrible place, the field hospital, full of suffering - and I, along with others like me, novice nurses who knew nothing of war, found myself thrust into this theatre of pain ill-prepared for the sights and sounds I was soon to encounter. There was blood, so much blood that it was scarcely possible to walk from one end of a ward to the other without its cloying smell dogging your footsteps. We were all green, in more ways than one, at the start of it, but to my amazement after just a few short weeks I found myself almost immune to the regular, everyday tragedies unfolding before me. Boys - they were just boys, frightened, far from home, their uniforms in tatters and caked with filth, but still boys. We did our best, but it was often a fruitless task. Most died, if not of their wounds then of infection, gangrene, or shock. Amputations were common and distressing.

But there were also those who were unscathed by bullet or shell, yet who suffered as much, if not more, than those with physical wounds.

Jack was one such, a captain in the Irish Guards. He would sit for hours staring into space, hands held firmly over his ears, his thin body shaking from head to toe like an apple tree in a gale. A nurse called Alice usually attended him, but after her accident I was summoned by Sister Hawkins and tasked with his care. I would sit with him and stroke his arm, try to soothe him. At first he hardly seemed to notice, but then gradually, very gradually, he began to take in his surroundings and respond to my voice - just a little, just enough to encourage me that, yes, here was one I could repair, bring back from the bleak prison of his memories.

And so he began to talk, although at each distant rumble of shellfire he would cringe, panic playing about his features until I would rest my hand upon his and prompt him to continue. It was his smile, that small, nervous smile, which had such an effect upon me, I think. It was as if there were two characters within; the one a carefree, slightly self-conscious boy with a wonderful sense of humour, the other a haunted shade who had seen things no man should see. When he was well enough to return home for compassionate sick leave I was also able to obtain special dispensation to accompany him - and there, in England in the winter of 1915, we were married.

Jack would never return to the battlefield. He was incapacitated by the slightest unexpected sound, and the medical board found him quite unfit for further service. Inside I rejoiced, although I knew that he greatly missed his friends and the comradeship he had depended upon for survival. I kept the newspapers from him for this reason. Although the journalists tried to bring an optimistic slant to bear upon the terrible events at the front, it was plain to me that some awful, unprecedented abomination against humankind had taken place, with loss of life on a previously unimaginable scale - and Jack’s comrades, those who had remained, were either dead or bore terrible wounds as testament to the slaughter. We used to see them in London, the walking wounded, men so maimed that passers-by, to their shame, would cross the street rather than face the truth. But who could really understand what was taking place just a short sea journey away, unless they had been there? Yes, Londoners could sometimes hear the sound of the guns if the wind direction was favourable, but the distant rumbling gave little indication of the carnage and destruction that could be wrought by heavy artillery upon fragile flesh and bone.

And that is what helped us make our decision when we were offered the cottage, for the guns upset Jack so. A cousin on his side, prompted to visit in support of his infirmity, brought the possibility to our attention: that we might escape the remainder of the war altogether and start a new life together in rural Ireland. There was a cottage, part of a once larger estate, in need of a new tenant. It was habitable, pretty, and in need of a feminine touch to bring it to its full potential. It was owned by a Mr William Benjamin, some ex-government official who was known to Jack’s cousin; the formalities were attended to in very short order.

As we stepped off the boat at Rosslare and prepared for the journey westward we had little intimation of what lay ahead. Would that we had been spared the dread chapter to come, that we had turned back to the safety and comparative comfort of England. But that was not to be, and I must press on before my resolve fails me.

We took the railway across the south, through Waterford and on to Killarney before bending north to Farranfore and beyond. I found the countryside restful and Jack did also. We both felt, I believe, a peace we had not enjoyed for many months. For myself, the stresses of the field hospital had left their mark upon me, and I had been prone to my own periods of melancholy as I recalled the plight of the wounded and the primitive facilities they were obliged to endure in Ghent. Jack spoke little during the journey but the dark patches beneath his eyes had faded somewhat and I began to see flashes of what the young man of 1914 must have been as he set off to war, little imagining what awaited him in the mud and misery of Flanders. As we alighted at the tiny station to be met by Mr Benjamin’s pony and trap, I confess that my spirits lifted at the prospect of a new beginning, a God-given chance to put the war behind us for good.

‘You’ll find everything in order,’ Mr Benjamin declared as we drew up to our new home. He was a smartly attired man approaching middle age, perhaps in his early forties. He wore a quilted cap despite the warmth of the day and a fully buttoned waistcoat beneath his jacket, the smart cut of which betrayed his English origins, for there was scarcely a trace of Irish in his accent.

We had been told by Jack’s cousin that Benjamin had been a man of some influence in London, but he had forsaken his career for the quieter life. ‘I shall be close at hand should you need anything,’ he continued. ‘Remember that, won’t you?’

‘I shall, and thank you for your kindness in agreeing to meet us off the train,’ I replied. ‘I don’t know how we should have found the cottage otherwise.’

‘We should have become restless wanderers,’ Jack said with the ghost of a smile, which warmed my heart as I saw it form upon his lips. ‘My sense of direction is not what it once was.’

‘My pleasure,’ Benjamin said, doffing his cap. ‘You’ll find me just up the lane by the crossroads. Look for the white gate. I trust all will be well.’

And off he went, leaving us with a curious frown and our luggage by our feet. We stood silently for a moment or two, drinking in the charm of our new home: the thatched roof and half-leaded windows, the colourful hanging baskets of gay spring flowers and the pretty garden all seemed impossibly dreamlike, almost too good to be true. Indeed, we discovered later that our thoughts at that moment had been identical - that we would awaken suddenly from this most delightful dream to find ourselves back in Ypres. Neither did I dwell on Benjamin’s odd farewell - at the time I dismissed it as a peculiarity of the man. Of course all would be well. Why ever would it not be?

Those first weeks were idyllic. The weather smiled upon us as we settled into our new routine. Jack would sit reading and dozing in the garden while I attended to my task of turning the cottage from an attractive prospect to a home we could call our own. It was not an onerous duty, for I needed practical things to occupy my mind, lest it be filled with disturbing images and recollections from my time close to the lines. But already, like a badly processed photograph, those days were beginning to fade and lose their clarity. It was almost as though the memories which stirred in my head were those of a different person, another life - which, in a way I suppose they were. The images were worse at night, when not only Jack but on occasion I too would awaken suddenly, gripping the bedsheets in fright as we sought to expunge whatever ghastly image had returned to haunt us from the conflict. We were able to comfort each other, however, united not by entirely common experience, but certainly by a deep understanding of each other’s fears, which the quiet, calm atmosphere of the cottage helped us both to if not altogether subdue, then at least begin to put into some kind of manageable perspective.

And so in a matter of weeks I transformed the cottage from its original charming but basic aspect into a cosy haven which catered for my own tastes and Jack’s too, although my new husband was content to leave the choice of furnishings and decor to me because, as he told me with his shy smile, he had little experience of such things, having only left his childhood home upon volunteering for Kitchener’s army. The only other home the dear man had known was a dugout and a trench filled with water, mud and the body parts of dead comrades and enemies alike.

‘You are a talented woman, Jenny,’ Jack told me one morning as we sat outside. ‘And I am a lucky man who deserves much less.’

‘I’m glad you like it,’ I said. ‘If it makes you happy then I am all the more content.’

It was a beautiful spring day and the garden was bursting with the smell of wild-flowers. We sat together listening to the birdsong, the occasional clatter of a cart as it passed along the lane or the merry whistle of a farmhand on his way to tend the cows in the neighbouring field.

‘I dreamed of Mons last night,’ Jack said.