London Folk Tales (8 page)

Authors: Helen East

A ripple of uncertainty ran through the group. To hand over your weapon was a foolish thing to do, but the boy confused them – he seemed so much at ease and he sounded like a Norman too. And now he was mimicking them, showing them each so manly and tall, and then portraying himself as very small; it was absurd to think he could be a threat to them all. He did it so delightfully too. The nobleman relaxed and laughing tossed the boy his sword.

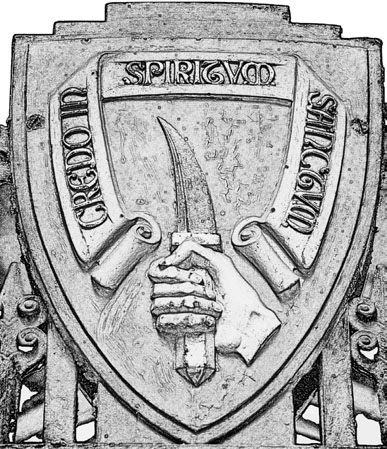

Rahere caught it by the hilt, as if well used to handling it, then pressed its point into the earth, and, leaning on it, levered himself up. For a moment he hung balanced there, hand on sword, upside down, feet high up in the air. And then, unbelievably, he started to spin. How it was done I do not know; it was something new he had taught himself to do, and there is a picture of him doing it, in the church of St Bartholomew the Great. But that is running ahead of the tale.

For that moment back then changed everything. By the time Rahere had somersaulted back to his feet and solid ground, there were whistles and calls and cheers of applause from everyone around. With a flourish he pulled the sword free, wiped its point perfectly clean, and returned it to its owner. As he did, he looked him full in the face again, and then, very slowly, smiled. Rahere was good looking, but his smile was utterly beautiful. It lit him up from within; transformed him. He saw the reaction in the young man’s eyes and turned as if to walk away.

‘Wait!’ the young lord cried. ‘Walk with me a while.’ And as they fell into step, he reached out his hand. ‘Come young friend,’ he said, ‘when did you last eat?’

And so, Rahere walked into another kind of life. The pinnacle, he thought, of all his dreams. But he was destined to go higher still. For while he stayed with his new friend, Rahere learnt swiftly, watching and listening and seeing how he should behave to please all those around him. And so well did he do, it was soon hard to recognise the poor boy he had been. The nobleman was proud of his young protégé. When he thought that Rahere was ready, he took him to the royal court, and introduced him to the king.

That was how Rahere became King Henry’s jester. And since he persisted in mastering every new instrument that came his way, it wasn’t long before he was one of the king’s favourite minstrels too.

He was surprisingly popular throughout the whole of the court. His cheerful wit was well appreciated in a place that set such store on skill with words. But he was careful to keep his jokes kind, though clever, for he could see that sharper tongues were apt to end up cutting themselves deepest. Rivalry was rife amongst the courtiers, and those most loved so often seemed to overreach themselves, and fall from favour, helped on their way down by many waiting restlessly below. Rahere steered a steady course, friendly to one and all, balancing between factions as skilfully as he had had to do upon the hilt of that first sword. And he was lucky, too, in finding influential support from a most unexpected source.

Queen Matilda was a deeply pious woman. Although she truly loved her husband, she was not fond of some of the pleasures of his court. Yet young Rahere she took under her wing. She liked his gentle playful nature, and she loved to hear him sing. And so she had him instructed in the music dearest to her heart – that of the Church. To help in this she also made sure that he was taught to read and write. Latin at first, of course, but when she saw his overwhelming thirst for knowledge, she encouraged him to study other languages as well. For Rahere, with his hungry mind, the ability to decipher script was a gift beyond all others; it opened the doors to people’s thoughts, in lands he’d never dreamt of. And he repaid the queen with such devotion that she trusted him absolutely, and when her son Prince William was born, she thought there was no better playfellow to sing her child to sleep, and watch over his first steps, than young Rahere.

And so Prince William Adelin, the apple of King Henry’s eye, and sole heir and hope of all of England, grew up treating Rahere as if he was an elder brother who could somehow always find the time to play or sing or tell him stories.

For Rahere that was the happiest of times. But destiny, it seemed, had other plans. When the prince was fifteen, Queen Matilda died. London went into mourning. The king was distraught. William sat in his in his mother’s rooms and wished that he could weep in peace. But since such behaviour was not proper for a prince, he returned to court society, and tried to drown his grief in wild excess. And although he married the following year, and was instated as Duke of Normandy soon after that, his right royal indulgences went on unchecked. Even when Rahere reasoned with him, he failed to talk him into better sense.

That autumn, King Henry was returning with the prince from a visit with the King of France. It was after the harvest, they were laden with gifts, and fine French wine, of course. At the port, they met FitzStephen, a long-term friend of the family. It had been his father who had captained the ship that took the Conqueror to England in 1066. Now FitzStephen was waiting with a ship of his own, built to be the swiftest in the fleet, according to a special new design.

‘My White Ship is made to fly across the waves,’ he boasted. ‘We will carry you to Hastings, as my father took yours, but yet we will arrive in half the time!’

The king was sorry, he’d arranged to go with someone else, and they were due to sail within the hour. But Prince William was delighted to accept, and as the vessel was so fast he saw no need to hurry off. Besides, there was too much fresh wine to taste.

Long after the king had left, William and his entourage were dancing all along the shore and toasting the White Ship’s success. They were enjoying themselves so much that they refused even to pause and let the priest come past and bless the new ship’s boards.

By the time they set off it was dark, and most of the crew were also drunk. The lights of the king’s ship, far ahead, had long since vanished out of sight. ‘He could be landing before long,’ a sailor said.

The prince’s party took this as an affront. Determined not to arrive last, they challenged FitzStephen to make good his boast. ‘Prove your ship is truly fast!’ ‘Overtake the king!’ they cried.

And so the captain tried. He altered the course to make it more direct, though he might have guessed that in the night this was suicide. Not far from Barfleur port, they struck a submerged rock, and the ship very quickly capsized. A butcher survived because the ram skins he wore kept him warm and afloat until he was found at dawn. But everyone else was drowned.

William Adelin had been put into a boat, but climbed back to try to get his sister out. FitzStephen managed to swim up to the surface, but when he heard the prince was lost, he let himself go down.

It is said King Henry never smiled again. The flower of the royal youth gone in one swoop: two much-loved illegitimate sons, a daughter, a niece, dear friends, half of the English court and any hope of smooth succession to the throne all sank with William Adelin, heir to the English throne.

But while the country reeled with the tragedy, there were many who pointed the accusing finger. ‘A judgement from God’ they wrote, ‘A punishment for the sins of the flesh.’

Rahere was overwhelmed with sorrow and a sense of guilt. He begged permission from the king to make a pilgrimage to Rome, to visit the shrine of St Paul, the patron saint of London, and to pray on behalf of them all. Henry readily agreed, and Rahere set out at once. Dressed as a penitent, in rough cloth, armed only with a pilgrim’s staff, it was the first time for many years that he had felt the London streets beneath his bare feet. It was hard to have so little again, but yet he felt curiously free. Although, with only a small scrip of money, he soon remembered that there was no romance about being hungry.

Travelling by foot it was a journey of many months to Rome, and one that plenty did not survive. He must have thought of William Adelin as he lurched across the Channel, crammed in the ship’s hold, with 100 other stinking and vomiting penny-paying passengers. It was a long walk down through France and a steep climb over the high snow-capped mountains into Italy. Rough too, sleeping in monasteries and pilgrim dormitories, sharing beds with others, fleas and lice. And in such close confines, diseases of all sorts passed from one to another as easily as greetings.

Rahere, however, did not get truly sick until he had arrived in Rome, and done penance for his sins to St Paul. As he had promised Henry, he visited the very spot where the saint was martyred – the Three Fountains – outside the city walls. This place was also famous locally, for mosquitoes. They carried a disease known as ‘Roman fever’, which nowadays we call malaria.

Rahere stayed there praying for several nights and soon found himself shivering and burning by turns, aching in every limb. Other pilgrims found him, and, seeing he was desperately ill, they carried him to the hospice of St Bartholomew. Although the monks there cared for him as best they could, everyone assumed that he would die.

But in his wild delirium, Rahere had a vision. It began with the roar of a thunderstorm which turned into a dreadful dragon-winged beast. Catching him up in its great clawed feet it carried him high, high, high into the air, then suddenly dropped him like an eagle might toss scraps to its young. He landed on a narrow ledge, and peering over the edge he saw an awful abyss. But far, far below he sensed something moving. Though terrified of falling, he felt an awful urge to see what it was.

Then, all at once he felt someone holding him safe, and it made him feel so calm, he was able to look deep down. Right at the bottom were many minute creatures, like insects swarming. But now he saw they were children playing, boys as ragged as he himself had been. And the place they were in was where he had grown up, Smithfield, in London. Where the smiths worked beside the horse pond and the Kings Fair was held every year. The ground was so boggy that it was never wholly dry, and in winter time it froze so hard that if you could find two sheep bones and strap them to your feet with strips of skin, then you could slide across the ice with tremendous speed. Rahere remembered the thrill of it even now. But as he looked he saw things he had never noticed then.

All around there were people in such poverty that their skin was hanging off their bones. Some had broken limbs, or hands that were missing fingers or thumb, or sores festering on faces and arms. It broke his heart to see it, and to think of the comfort he had lived in at the court. And there and then, he swore that if ever he should recover and return home to London, he would build a hospice for the poor where there was none; a place they could go for help and for healing, whether they could pay for it or not.

At that moment, once again, Rahere felt strong hands supporting him. And now he pulled back from the edge, and looked to see who it was. It was a man with a face of extraordinary sweetness and light in his eyes almost too bright to bear. ‘I am Christ’s apostle, St Bartholomew,’ he said. ‘I have come to help you, and to command you too. In that place that you have seen in your dream, you must build a great church in my name, and your hospice by its side. If you do what I ask, never fear; I will be here to support you in the task.’

Then Rahere felt his head clear, and his fever go. He opened his eyes and looked up. By his bed a priest was standing, ready to administer the last rites. Filled by the strength of his dream, Rahere returned directly to England and the king. And when Henry saw how changed he was, and how inspired, he promised him all that he required by way of land and money and authority too.

The land Rahere chose was the marshy flat expanse of Smithfield. And as soon as the building work began, three holy travellers came from the Byzantine Empire, as well as Alfune, one the wisest men of Christendom; they planned it together so it became a place where all could meet in brotherhood, and peace. The church was built with a priory on the south side, and a hospice for the poor beside it, and Rahere named it all St Bartholomew’s. Even the Kings Fair that continued there every year was then called after the saint.

Rahere himself was the first prior, and he also presided over much of the healing that took place in the hospice. And even after his death, they say, the sick were healed, the blind could see, and the lame were made to walk again. Today you can still feel the strength of his spirit in the church. Some claim they have seen his ghost, too, by the altar. As for his hospice, it was moved and rebuilt elsewhere as St Bartholomew’s Hospital. But even in this altogether different modern world, it remains a place that anyone in need of healing can go to, without having to pay.

W

ITCH

W

ELL

Ding Dong Bell, Pussy’s in the Well

What she does there

No one can tell.

Once upon a time, when pigs spoke rhyme, and London was a small place in anybody’s mind, there were wells all around the town. Shepherds Well to Streatham Wells, Sadler’s Well to St Chad’s Well, Woodford Wells to Bagnigge Wells, St Bride’s or Bridget’s Well, Mossy Well or Muswell, Clerks Well to Camberwell, Briton’s Well or Cripplewell. Some had fresh water, good for drinking, and there were always queues of children, women and water-carriers. Some had sweet water, good for healing, and people came to cure their sore eyes and stiff legs and sad hearts. Others again had scummy water that was good for hiding, and people came with all sorts of dark secrets, and threw bodies, bones, and even babies down there.