London Folk Tales (16 page)

Authors: Helen East

Mindful of the good advice he’d been given, he didn’t protest out loud, but pointed into his mouth and shook his head. Then he took off his pack and made a dumb show of having things to sell and being very hungry too.

Meanwhile, however, his poor dog, who had never been treated so badly in its life, began to run round barking hysterically. The master of the house himself came out to see what was going on, and Henry was hard put not to call out to his friend. But this time he saw the alderman in an altogether different light. Gone were his gentle charitable ways! Despite the pitiful show, Henry put on, he had his footman out in a moment, and Henry and dog were kicked round the house and out of the gates. What was worse, he wasn’t even allowed to gather up his pack again, and all his goods, were left behind. If Henry had indeed been trying to make a living as a pedlar, that single thoughtless uncharitable act would have ruined him.

He was glad to get back to his own clothes, and his own life. But he couldn’t forget the experience he’d had. It had taught him so much. Over the next few months he went out as a poor man again and again, and now he saw the generosity of some people too. Sometimes they were people that he knew, and he was delighted to find them as kind as they had always seemed. But more often than not, it was people along the way, a few barely better off than beggars themselves, who would give him a drink, or a piece of bread, or simply treat him as if he also was a human being worthy of the name. In the back of his mind he always hoped to meet with John Chapman again, and to say ‘this time it is I who should thank you, for telling me what you knew.’

Little by little, as the years went by, Henry Smith was more often a penniless pedlar than a rich silversmith. Mostly he was on the south side of the river, spreading out from London into Surrey and Kent. From parish to parish he went, testing the true nature of the people he met. In time he became so well known, with his little dog always at his side, that he gained a new name, ‘Dog Smith’.

One place where he felt welcome, more often than not, was Lambeth, a new but fast-growing parish on the south bank of the river, surrounded by fields and farms. Perhaps it was because it was not a rich area, that the people seemed more generous there. Often Henry would stop in what became his favourite spot, the churchyard of St Mary’s church. It had a particularly sunny seat, which no one ever objected to him occupying for a while. In the end, the parishioners got so used to seeing the old man resting there, with his faithful friend lying at his feet, that they put out a little wooden bowl full of water for the dog to drink. By now the poor creature was old and getting feeble, but she always found the strength to wag her tail in thanks for any little kindnesses. Henry felt he’d lost part of himself when she eventually died.

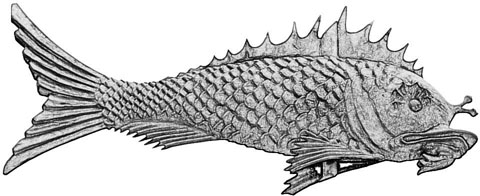

Soon after that, the rector of St Mary’s church, to his great surprise, had a visit from Henry Smith, renowned benefactor and wealthy silversmith. For some reason that he could not fathom, Mr Smith offered a considerable sum of money for an old pedlar’s dog to be buried in the churchyard. It was the sort of sum that could not be refused. The worthy gentleman also paid for a fine stained-glass window for the church, depicting, of all things, old Dog Smith himself with the little creature in question. But, as Henry explained, it was not the first time a pedlar should be represented in so grand a way. For in Swaffham, a pedlar called John Chapman had come into a great sum of money, and had paid for a whole new church – with effigies of himself in it. And his dog! The rector had heard of the generous John Chapman, but could hardly imagine so respectable a gentleman could ever have been a poor pedlar. But as Henry said, blessed are the poor and meek … and the window he gave the church was a treasure indeed.

After the loss of his dog, Henry was more often in his poor clothes than as himself. In this guise he returned once more to Mitcham, and this time the alderman had him caught and whipped as a vagrant, to teach him a lesson he would never forget.

He did not forget it either. When the time came for him to die, his will was a surprise to everyone. His large estate and other assets were divided up between those parishes and people who had shown him true charity. Lambeth in particular did very well, and St Mary’s church was bequeathed an osier ground, later enclosed as a meadow, called Pedlar’s Acre.

But Mitcham got nothing at all – to the surprise and disappointment of the alderman, who had always cultivated Henry Smith as a personal friend.

R

EBECCA

AND THE

R

ING

Well it wasn’t in my time, nor was it in yours. It was the time when rivers ran their own course. The Thames slipped by as stately easy as you please, then raced full fierce and fast, and once past London town, the River Lea came pouring down to feed it from the north-east side. Both rivers ebbed and flowed with the tide, the Lea so powerfully that tidal mills along its banks ground corn both day and night.

Queen Matilda, Henry I’s wife, had reason to respect its might. On her way to Barking Abbey she tried to ford the river at ‘Brembel Lega’, the ‘bramble meadow land’ that gave its name to Bromley. Her pious purpose paramount, she forced her horse on, failing to feel the full pull of the current until it dragged her down. She almost drowned. Restored to solid ground at last, she asked for a bridge or ‘bow’ to be built. So the area became ‘Bromley by Bow’, and prospered accordingly, for there were few places at that time where people could safely dance as the new song asked, ‘Over my Lady Lea.’

Hackney Wick was just a kink in the bank, a place where small boats could harbour. Stepney was Stebenhythe, a simple landing place. There were no barriers to hold the river back, or drainage ditches and diversions to claim the land from the water. To the east of London, all was mostly marsh, the rivers winding through, with various flooding branches. A damp home for fishermen and eel catchers, and a haven for wildfowl and all who fed on them; although hunters carefully picked their way for fear of finding a watery grave.

But little by little, London townsmen were turning their eyes towards it. Bishops of London owned the Manor of Stepney, and one, Dunstan, on becoming a saint had his name added to the church there. Edward I improved the banks, and made Stepney a place for a parliament, and Mayors of London, encouraged by this, promptly acquired estates. It was land where they could expand, and perhaps enjoy a bit of sport, within the easy reach of court. If they wanted more, they could follow the marsh north, and meet with Epping Forest royal hunting grounds. So – as in those days a moment caught in the regal gaze could raise one from the depths to the heights of praise – a Stepney Marsh mudbank, just an ‘ey’ in the ooze, gained name and fame as the ‘Isle of Dogs’ where a royal pack could kennel. And then James I came to the throne, and wanting the fresh air, clear of the Plague zone, and the chance to hunt ever nearer to home, he built his hunting lodge and palace at Bromley by Bow.

So, everyone who was anyone was soon seen on the Stepney flatlands. And one who was definitely someone – in his own eyes at least – was the noble Sir Berry. He was out hunting with a party of friends, celebrating the christening of his son and heir. Full of the joys of life, and the happy assurance of a stable future, he gave his horse its head, chasing after a hound that had got the scent of something more than fowl. Not noticing how far back his friends had fallen, nor how late the day had become, he was caught suddenly in a thick marsh mist that rose out of nowhere. It was so clammy and confusing, even the dog was utterly confounded and crept back whining at the echo of its bark.

Sir Berry reined in and turned back to join the others, but it was impossible to retrace his steps. Hour after hour, he wandered in circles, until the horse stopped abruptly and refused to take another step. Then he heard a sound from behind that at first he took to be a hunting horn. When it came again he realised it was the wail of a child. He turned the horse and headed back towards it, and now the beast went on without objection. At last they came to a flickering light which turned out to be a candle in the window of a ramshackle house, hardly more than a reed hut. The dog was already at the door and he pushed in after. Inside a fire was roaring, with a woman sitting by it. She turned as he entered.

‘Thank God,’ he said, ‘I thought I was lost.’

‘Thank Lady Luck too,’ she answered. ‘It was her wheel who brought you here.’

He was taken aback, both by her words and the way she spoke, so directly, without deference. ‘I am no gambler, guided by luck,’ he said curtly. ‘In these settled times I can decide my own path.’

‘I wouldn’t be so sure of that,’ she replied. ‘But come, sit by the fire. There is little enough to eat, but you’re welcome to all I have. Or perhaps you would like to see to your horse first. Tell me, does he have a white blaze between his ears?’ She smiled at his astonishment. ‘Ah, then you are the man I was expecting. As fate foretold. And if you want your proof of fortune’s power, retrace your steps tomorrow in the light, and see the place your horse had stopped before you heard my daughter cry.’ It was only then that he saw a baby, cradled in her arms. A tiny creature younger than his son, but with eyes of the most astonishing blue.

‘Hold her, if you will,’ the woman said, ‘while I find you some food. And let you get to know her too, for tomorrow I will be gone, and she must go with you. Forgive me, but she will repay the task of looking after her. Rebecca is her name, and she is destined for good fortune and fame. As I was told, and swear it’s true, her fate is to marry into the noble family of Berry. So whoever you are, sir, she will well look after you.’

Shocked into silence, Sir Berry held the child, ate the food given him, and waited for the first light of morning to escape. As soon as he could see he crept outside, got onto his horse, and for want of other options, retraced his steps. Soon enough, he came to where the horse had halted so determinedly. Another step, he could see now, would have landed them both in the water, the River Lea still running so high and wild they would not have stood a chance.

The dog was whining and running backwards and forwards in the direction of the house. Again Sir Berry could hear the child crying. But this time, as he stepped inside, the woman said nothing. She sat in the chair, cold and dead. The prophecy still running in his head, Sir Berry picked up the child, wrapped her in soft well-woven cloth, and carried her back to the river. ‘This child to marry into my house? This girl to wed my son? This nobody?’ He could not let it be. ‘Her fate ends here!’ he cried, and threw her into the angry water. Then in the early morning sun he made his way back home.

The river wound its way down towards a mill. The cloth was tightly woven, the girl held buoyant. Above the mill race, a fisherman had set his net and was already there to see what the night had brought. To his astonishment, he saw a child spinning in the stream and quickly fished her out. He and his wife had no children of their own, and they were delighted at the river’s gift. Embroidered carefully in the corner of the cloth was the letter ‘R’. When the parson told them what it said, they called her the first name that came into their head – Rebecca. The river’s daughter.

Time passed, and Sir Berry’s son, John, grew into a fine youth with his father’s love of hunting. One day, while riding by the Lea, he felt thirsty, and seeing a cluster of fishermen’s huts he stopped to ask for a drink. An old man called for his daughter to bring out a jug of small beer, but the moment John looked into her blue eyes he forgot his thirst and everything else. They talked a little together and the more he heard her speak the more he wondered how she could be a simple fisherman’s daughter.

‘Ah, but Sir!’ her foster father explained proudly. ‘She is the daughter of the Lea, she is. She came with her name embroidered on fine cloth and no matter what we teach her she can never learn enough. She can sew and spin and do anything. Next thing she’ll be reading and writing!’

The lad was so love-struck, he couldn’t keep his mouth shut, and word of this girl soon reached his father. What he heard made him so concerned that he got on his horse and went straight to the girl’s house. One look at her and he knew right enough, and his fears were confirmed by the cloth. As he listened to her father, his thoughts were whirling, but soon he saw what line to take.

‘It seems that she is destined for a higher life,’ he said. ‘Would you like her to read and write? If you trust her to me, I will do what is right.’

The fisherman and his wife were broken-hearted to let their daughter go. But they did not want to stand in her way. And so, for the second time, Sir Berry took Rebecca on his horse before him and rode away.

Taking her to a dressmaker he had her fitted out with cloaks and gowns and all she might need for a long journey, as if he was indeed the second father to her that he had promised to be. Meanwhile he wrote to his cousin in the North country.

This beautiful girl is going to destroy both my son and myself. Guard her carefully and as soon as you may have her killed for John’s sake