Little Lost Angel (42 page)

Melinda Loveless, Laurie Tackett, and Hope Rippey are now serving their murder sentences at the Indiana State Women’s Prison in Indianapolis. Toni Lawrence, who didn’t have the resolve to stop them and who passed up numerous opportunities to summon help or simply just walk away, once again finds herself in the company of killers, for she too is confined at the Indianapolis prison, doing time for her role in confining Shanda.

Each girl has filed an appeal in hopes of having her sentence reduced, but if there are no reductions Toni will walk out of prison in 2002, when she is twenty-five; Hope in 2017, when she is forty; and Melinda and Laurie in 2022. At that time, Melinda will be forty-six, Laurie will be forty-seven.

* * *

In February 1994, the last time I saw Steve Sharer, he and his wife, Sharon, were relaxing in their living room—the same room in which they’d last seen Shanda.

Photographs of Shanda hung on the walls, daily reminders of what once was, frozen moments of a securer, happier time.

The passage of months had eased the tension from Steve’s face; the iron look of determination he’d worn in the courtroom was gone. Although it was still difficult for him to discuss his daughter’s death without breaking into tears, he seemed to finally be at peace with it in his mind.

“I know she’s waiting for me in Heaven, so I have to make sure I lead a good life so I can see her again,” Steve said.

After Shanda’s death Steve and Sharon received dozens of phone calls and letters from parents and youngsters asking for advice for problems they were having, most concerning the peer pressure children face in today’s world.

They diligently responded to each inquiry, opening up their hearts with advice that might possibly prevent a reoccurrence of the pain they feel.

“I tell them all the same thing,” Steve said. “I tell parents

to listen to their children and children to listen to their parents. It’s a simple message, but sometimes we forget it.”

Forgetting is not something that Steve and Sharon have the luxury to do anymore.

“I have a little ritual I go through every morning when I leave for work,” Steve said. “I look at the picture of Shanda that I keep on my dashboard. I kiss my fingertips, then touch her face and tell her that I love her.”

* * *

My last visit with Jacque Vaught was around the same time. In the months after Shanda’s death, Jacque, who had spoken so eloquently during the sentencing hearings, received numerous invitations to speak to parents and students at local schools.

After seeing the effect her words had on adults and youngsters, the speaking engagements became her passion, her way of dealing with Shanda’s death. She and Sandra Graves, the grief counselor who helped her recover from depression after the murder, formed an organization called “No Silence About Violence,” in hopes that it will one day have the same sort of widespread effect that Mothers Against Drunk Drivers has had in raising awareness of the destruction done by intoxicated motorists.

By early 1994, Jacque had spoken at dozens of area schools and expanded her horizons, accepting invitations to speak in cities around the country, most recently in St. Louis and Seattle.

She begins each speaking engagement by relating the events that led to Shanda’s abduction and grimly leads her audience down the dark path that ends with Shanda’s fiery death, sparing no grisly details. Jacque then looks parents straight in the eyes and tells them that they shouldn’t try to be their children’s friends.

“They have enough friends,” she says. “You be a parent. You watch who they run around with. And you, with no uncertainty, step in when you think they are running with the wrong crowd.”

To children she says, “Remember what happened to Shanda. Don’t you ever forget it. It could happen to you or

to your friends. Shanda’s friends never thought it could happen. Neither did Shanda. Neither did I.”

The effect on listeners is palpable. Parents cry and children come up afterward and hug Jacque.

“I know some people question why I’m doing this and why I don’t put my daughter to rest,” Jacque said. “Maybe most people would react that way, try to put what happened out of their mind. But I could never do that. If the lesson of Shanda’s death can save one other life, it’s been worth it.”

As Jacque talked, her eleven-month-old granddaughter, Aspin, grabbed the edge of the living-room couch and shakily pulled herself to her feet. Jacque leaned over and asked Aspin, “Where’s Shanda, where’s Aunt Shanda?”

The toddler turned and pointed toward the shadow boxes that hung on the wall, the glass cases filled with photographs and mementos of Shanda’s life.

“I can’t tell whether she’s pointing to Shanda’s picture or to Heaven,” Jacque said, pulling Aspin onto her lap and hugging the infant closer to her chest.

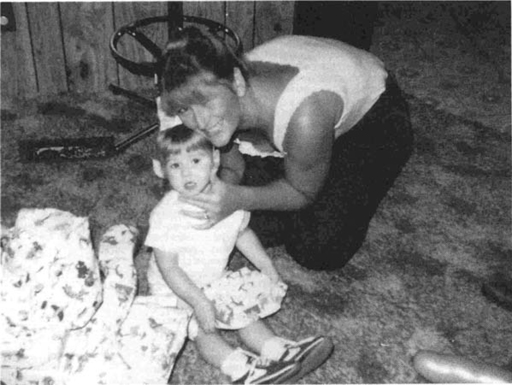

Shanda and her mother, Jacque, on Shanda’s second birthday. (

Photo by Paije Boardman

)

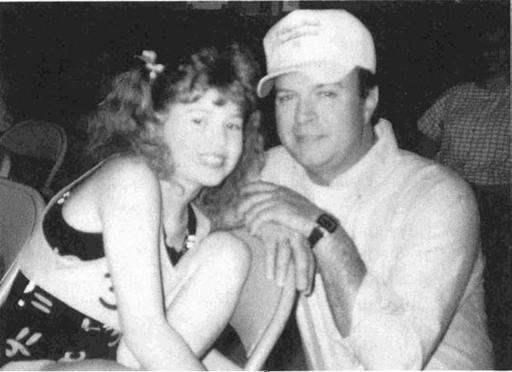

Shanda relaxing with her father, Steve, after her gymnastics meet. (

Photo by Sharon Sharer

)

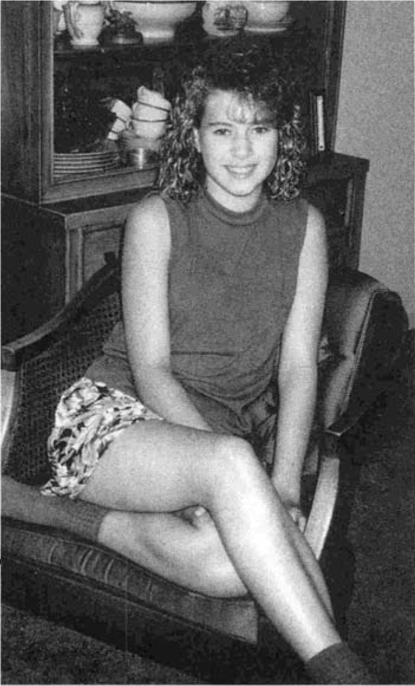

Shanda at nine. This is her mother’s favorite photograph. (

Photo by Jacque Vaught

)

Shanda, three months after she turned twelve, four months before she was murdered. (

Photo by Betty Sharer

)

Amanda Heavrin, fourteen, wanted to be more than friends with Shanda.

Melinda Loveless, shown in her eighth-grade photograph, was Amanda Heavrin’s lesbian lover. She grew insanely jealous of Shanda’s friendship with Amanda.

Melinda Loveless’s home was the first stop by the killers on the night of Shanda’s murder. (

Photo by Michael Quinlan

)

The home of Shanda’s father, Steve Sharer. Shanda was lured out of the house and abducted by four teenage girls. (

Photo by Michael Quinlan

)