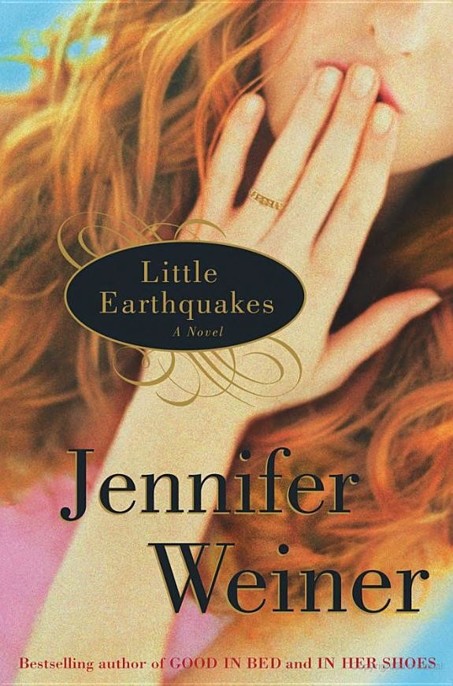

Little Earthquakes

Jennifer Weiner

In Her Shoes

Good in Bed

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2004 by Jennifer Weiner, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 0-7434-9990-5

First Atria Books hardcover edition September 2004

ATRIA

BOOKS

is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You?

by Dr. Seuss, copyright TM and copyright by Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P., 1970, renewed 1998, used by permission of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

“Soliloquy” copyright © 1945 by WILLIAMSON MUSIC. Copyright Renewed. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For Lucy Jane

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

—M

ARGERY

W

ILLIAMS

The Velveteen Rabbit

I watched her for three days, sitting by myself in the park underneath an elm tree, beside an empty fountain with a series of uneaten sandwiches in my lap and my purse at my side.

Purse. It’s not a purse, really. Before, I had purses—a fake Prada bag, a real Chanel baguette Sam had bought me for my birthday. What I have now is a gigantic, pink, floral-printed Vera Bradley bag big enough to hold a human head. If this bag were a person, it would be somebody’s dowdy, gray-haired great-aunt, smelling of mothballs and butterscotch candies and insisting on pinching your cheeks. It’s horrific. But nobody notices it any more than they notice me.

Once upon a time, I might have taken steps to assure that I’d be invisible: a pulled-down baseball cap or a hooded sweatshirt to help me dodge the questions that always began

Hey, aren’t you?

and always ended with a name that wasn’t mine.

No, wait, don’t tell me. Didn’t I see you in something? Don’t I know who you are?

Now, nobody stares, and nobody asks, and nobody spares me so much as a second glance. I might as well be a piece of furniture. Last week a squirrel ran over my foot.

But that’s okay. That’s good. I’m not here to be seen; I’m here to watch. Usually it’s three o’clock or so when she shows up. I set aside my sandwich and hold the bag tightly against me like a pillow or a pet, and I stare. At first I couldn’t really tell anything, but yesterday she stopped halfway past my fountain and stretched with her hands pressing the small of her back.

I did that,

I thought, feeling my throat close.

I did that, too.

I used to love this park. Growing up in Northeast Philadelphia, my father would take me into town three times each year. We’d go to the zoo in the summer, to the flower show each spring, and to Wanamaker’s for the Christmas light show in December. He’d buy me a treat—a hot chocolate, a strawberry ice cream cone—and we’d sit on a bench, and my father would make up stories about the people walking by. A teenager with a backpack was a rock star in disguise; a blue-haired lady in an ankle-length fur coat was carrying secrets for the Russians. When I was on the plane, somewhere over Virginia, I thought about this park, and the taste of strawberries and chocolate, and my father’s arm around me. I thought I’d feel safe here. I was wrong. Every time I blinked, every time I breathed, I could feel the ground beneath me wobble and slide sideways. I could feel things starting to break.

It had been this way since it happened. Nothing could make me feel safe. Not my husband, Sam, holding me, not the sad-eyed, sweet-voiced therapist he’d found, the one who’d told me, “Nothing but time will really help, and you just have to get through one day at a time.”

That’s what we’d been doing. Getting through the days. Eating food without tasting it, throwing out the Styrofoam containers. Brushing our teeth and making the bed. On a Wednesday afternoon, three weeks after it happened, Sam had suggested a movie. He’d laid out clothes for me to wear—lime-green linen capris that I still couldn’t quite zip, an ivory silk blouse with pink-ribbon embroidery, a pair of pink slides. When I’d picked up the diaper bag by the door, Sam had looked at me strangely, but he hadn’t said anything. I’d been carrying it instead of a purse before, and I’d kept right on carrying it after, like a teddy bear or a well-loved blanket, like something I loved that I couldn’t bring myself to let go.

I was fine getting into the car. Fine as we pulled into the parking garage and Sam held the door for me and walked me into the red-velvet lobby that smelled like popcorn and fake butter. And then I stood there, and I couldn’t move another inch.

“Lia?” Sam asked me. I shook my head. I was remembering the last time we’d gone to the movies. Sam bought me malted milk balls and Gummi worms and the giant Coke I’d wanted, even though caffeine was verboten and every sip caused me to burp. When the movie ended, he had to use both hands to haul me out of my seat.

I had everything then,

I thought. My eyes started to burn, my lips started to tremble, and I could feel my knees and neck wobbling, as if they’d been packed full of grease and ball bearings. I set one hand against the wall to steady myself so I wouldn’t start to slide sideways. I remembered reading somewhere about how a news crew had interviewed someone caught in the ’94 Northridge earthquake.

How long did it go on

? the bland, tan newsman asked. The woman who’d lost her home and her husband had looked at him with haunted eyes and said,

It’s still happening.

“Lia?” Sam asked again. I looked at him—his blue eyes that were still bloodshot, his strong jaw, his smooth skin.

Handsome is as handsome does,

my mother used to say, but Sam had been so sweet to me, ever since I’d met him. Ever since it had happened, he’d been nothing but sweet. And I’d brought him tragedy. Every time he looked at me, he’d see what we had lost; every time I looked at him, I’d see the same thing. I couldn’t stay. I couldn’t stay and hurt him anymore.

“I’ll be right back,” I said. “I’m just going to run to the bathroom.” I slung my Vera Bradley bag over my shoulder, bypassed the bathroom, and slipped out the front door.

Our apartment was as we’d left it. The couch was in the living room, the bed was in the bedroom. The room at the end of the hall was empty. Completely empty. There wasn’t so much as a dust mote in the air.

Who had done it?

I wondered, as I walked into the bedroom, grabbed handfuls of underwear and T-shirts and put them into the bag.

I hadn’t even noticed,

I thought.

How could I not have noticed?

One day the room had been full of toys and furniture, a crib and a rocker, and the next day, nothing. Was there some service you could call, a number you could dial, a website you could access, men who would come with garbage bags and vacuum cleaners and take everything away?

Sam, I’m so sorry,

I wrote.

I can’t stay here anymore. I can’t watch you be so sad and know that it’s my fault. Please don’t look for me. I’ll call when I’m ready. I’m sorry…

I stopped writing. There weren’t even words for it. Nothing came close.

I’m sorry for everything,

I wrote, and then I ran out the door.

The cab was waiting for me outside of our apartment building’s front door, and, for once, the 405 was moving. Half an hour later, I was at the airport with a stack of crisp, ATM-fresh bills in my hand. “Just one way?” the girl behind the counter had asked me.

“One way,” I told her and paid for my ticket home. The place where they have to take you in. My mother hadn’t seemed too happy about it, but then, she hadn’t been happy about anything to do with me—or, really, anything at all—since I was a teenager and my father left. But there was a roof over my head, a bed to sleep in. She’d even given me a coat to wear on a cold day the week before.

The woman I’ve been watching walked across the park, reddish-gold curls piled on her head, a canvas tote bag in her hand, and I leaned forward, holding tight to the edges of the bench, trying to make the spinning stop. She set her bag down on the lip of the fountain and bent down to pet a little black-and-white-spotted dog.

Now,

I thought, and I reached into my sleepover-size sack and pulled out the silver rattle.

Should we get it monogrammed?

Sam had asked. I’d just rolled my eyes and told him that there were two kinds of people in the world, the ones who got things monogrammed at Tiffany’s and the ones who didn’t, and we were definitely Type Twos. One silver rattle from Tiffany’s, unmonogrammed, never used. I walked carefully over to the fountain before I remembered that I’d become invisible and that nobody would look at me no matter what I did. I slid the rattle into her bag and then I slipped away.