Listen to the Squawking Chicken: When Mother Knows Best, What's a Daughter To Do? A Memoir (Sort Of) (11 page)

Authors: Elaine Lui

Ma had seen firsthand the devastating effects that drugs could have on a family. Her greatest fear was that I would try drugs and screw up my life. Two of her five siblings were drug addicts. Many of her childhood friends in Yuen Long became drug addicts. Their lives were wasted, just like Little Geet’s. There was no way her daughter would ever use. We’d be at the Fairview Park country club and she’d bring it up, out of the blue, over dessert if someone happened to compliment me.

Wah, Elaine is getting so tall. What lovely skin.

“It won’t be lovely if she ever does drugs. She’ll be like my sister who had druggie pockmarks all over her face.”

We’d be over at Uncle and Auntie Lai’s for dinner and their perfect, pretty, smart daughter Sandra would bring home a volleyball trophy and Ma would point to Sandra and then to me and say, apropos of nothing, “If you ever do drugs, you’ll never be like Sandra, you’ll be a total loser with a gross body and nobody will want to come near your disgusting hands. Drug addicts always have ugly hands.”

This is what I call the Squawking Chicken’s famous Pre-Shame. Ma was constantly pre-shaming me, humiliating me in advance, making me afraid of the shame so that I’d never be foolish enough to earn it. Ma used Pre-Shame to scare me away from drugs. She relentlessly beat it into my head that drugs would be my downfall. Pre-Shame was kinda like Ma’s version of Pavlovian conditioning—protecting me from doing whatever it was that she didn’t want me to do by giving me a taste of what I could expect if I ever did it. By the time I was old enough to be exposed to the drug culture, I was totally resistant.

While shame was used to build up my immunity to drug temptation, Ma also used shame to build my confidence, and in particular my body confidence. Women struggle with their physical self-perception all the time. We want to be

thinner, curvier, taller, shorter, fuller breasted, more ample assed, it never stops. But I’ve never met a woman who is as satisfied with her physical appearance as the Squawking Chicken. With the exception of when she’s been ill, Ma has always admired her own body. When she was fit, she flaunted it. If she gains weight, she celebrates it. She’ll be on the couch, with her stomach gathering over her pants, and she’ll grab a handful of fleshy rolls, chortling, and talk about how what’s growing on her belly is keeping her skin smooth. “Old woman no good too thin,” she’ll say to my husband.

And when he replies, “Ma, you look good!” her response reliably will always be: “I am always look good!”

Perhaps it’s that she had to reclaim her own body after her rape. Perhaps it’s having been through so many health crises that she appreciates the parts of her that are actually working. Whatever it is, it’s not bravado. She genuinely believes that she always looks good. But she saw early on that as a young girl I was insecure about my appearance. Growing up a Chinese girl in North America, surrounded by blondes and brunettes, with blue and green and gray eyes, long, straight noses, and versatile wavy and curly hair, I longed not to be “other.” I hated that I was. I was ashamed of my appearance. I was ashamed of my body. So Ma shamed me to stop me from shaming myself. It seems counterintuitive and it’s

certainly not consistent with the nurturing, supportive techniques child psychologists in North America might recommend to parents hoping to build their kids’ self-esteem. But there’s a saying in Chinese that goes

Yee duk gung duk

—“Use poison fight poison,” the Chinese equivalent of “fight fire with fire.” Ma fought my body shame by shaming me, publicly.

What could be more mortifying than bra shopping for the first time? I was ten. My body was being weird. My breasts were growing and I started becoming conscious of my

nipples showing through my T-shirts. Jennifer, the blond girl who lived across the street, a year older, had already started wearing a bra and loved showing off her bra strap. I decided to wait until summer to get a bra because I didn’t want to introduce one into my life in the middle of the school year. My parents were living apart then and I was staying with my father. Ma was in Hong Kong and I went to see her for the summer holiday. As soon as I met her in the arrivals area at the airport she was all over me about not standing up straight. I told her I needed a bra and that I didn’t want people to see my body. She told me that if people had a problem with my body, it was their issue and not mine. The next day she took me to the department store.

Right away, Ma went over to the saleslady and started asking about training bras. I slowly moved away to hide in the far corner of the intimates section, trying to figure out how I could strangle myself with panty hose. All of a sudden, it was like an announcement coming over the PA system, only not. Just Ma, with that goddamn voice, calling me over. And in English, because Ma liked to show off in Hong Kong that she had a daughter who spoke English.

“ELAINE, I FOUND ANUDDA BLAH FOR YOUUUUUUUUUUUUU!”

Every head turned. Every shopper on that floor knew that I needed a bra. I was the girl with the situation coming

out of her chest that had to be taken care of. I rushed over to Ma, took her hand, and pulled her into the dressing room, begging her to be quiet, pleading with her not to publicize my junior breasts and bra requirements. She was so angry at my reaction, she spat out the following lecture, in English, just to make sure I would understand her in the language I used in my mind: “Your body, this natural. What you need, bra, this natural. Why you shame for something natural? Why you shame your body? If you shame your body, you shame yourself. When you shame yourself, everyone shame you.”

Ma was urging me to confront my own body and its changes to confront the truth about puberty. Over and over again, through my adolescence, she used shame to help me accept the reality of what I looked like, to

see

what I actually looked like so that I would stop trying to look like something else.

The summer after Grade 8 I returned to Hong Kong for summer holiday with copper hair. I’d been spraying it with a product that lightens hair when you apply heat to it. It’s supposed to make you blond. Since my hair is naturally black, the closest I could come was orange. Still, I did it so that whenever people would ask me about it, I’d lie and say that one of my parents was white. Ma shamed me for weeks like she did with my Barbara Yung teeth and the retainer.

She kept calling it “red hooker head” because the prostitutes who worked in the clubs always dyed their hair. Everywhere we went: “Do you know why Elaine has a red hooker head? Because she thinks she’s a

gwai mui

[white girl]! I spent a night with Alain Delon and she’s our secret love child!” And they all laughed.

Looking back, of course it was humiliating. Ma’s relentless shaming was difficult to endure. But she wasn’t shaming me for sport. It’s not like it was a good time for her either. As a Chinese girl growing up in North America, I was struggling with my cultural identity. As a first-generation child born to immigrants, there was no model for me to follow; I was part of a new breed. And the Squawking Chicken was the only Chinese force in my life who could help me find the balance between my environment and my heritage. Ma shamed me so that I would not suppress the Chinese part of myself to try to become something I could never be. I would never be a North American white girl. But I could be a North American girl with a Chinese background. I could stop being ashamed of being a North American girl with a Chinese background.

It took a lot of work. The North American influence can be overpowering. Through my teen years, surrounded by white friends, the Chinese half of me was like wax, soft and

malleable against the heat of desire to blend in. And every time I wanted contact lenses to lighten my eyes or picked the wrong shade of foundation to lighten my skin, Ma was there. To shame me—yes. But really to remind me who I was, to rebuild me.

I don’t ever remember Ma telling me that I was beautiful. It’s not that she ever said I was ugly. Or that she didn’t, on occasion, tell me I looked nice, even pretty. But between Ma and me, there’s never been that mother-daughter movie moment, somewhere in the third act, when she’s held my hand and through eyes brimming with tears, she’s whispered, her voice choked with emotion:

“Baby, you are so beautiful.”

For

starters, Ma and I don’t speak like that

to each other. Actually, we don’t speak like that to

anyone. Ma abhors affection—physical and verbal. She’s not great with

hugs

—giving or receiving. And corny talk is gross to her. This is partly cultural. “I love you” in Chinese is super, super cringey. In our language, people just don’t say it like that, straight up. We might say, “I care about you a lot.” Or “I like you so much,”

but actually uttering those three words, “I love you,” is uncommon. It sounds weird. It sounds uncomfortably intimate. “I love you” is used only between lovers, never as a general expression of feeling between anyone in any other kind of relationship, and even then it’s reserved for those very rare occasions, in total privacy and never as an open declaration.

But the Squawking Chicken’s emotional reticence goes beyond the standard Chinese reserve. She’s just not one to share her affection through words or gestures. Ma prefers to show her love through action. So if she ever did tell me she loves me, or that I’m beautiful, I think I would laugh. Or rush her to the hospital. Because that would be a sign that she’d gone insane. These are just not words that would ever come out of Ma’s mouth. Quite the opposite, in fact.

I was eleven years old when Ma first told me I wasn’t beautiful. Of course, we were at Grandmother’s mah-jong den. While Ma played, I watched the Miss Hong Kong pageant on TV. Back then, the Miss Hong Kong pageant was a big deal. There were only two main broadcasters in Hong Kong in the eighties. TVB was the most watched and most powerful. It had the resources to turn Miss Hong Kong into the major event of the summer, splitting each round into a weekend special, so that the pageant took up almost an entire month.

Everyone

watched Miss Hong Kong.

Everyone

talked

about Miss Hong Kong. And

every

little girl wanted to be Miss Hong Kong.

It was the day of the semifinals. The favorite that year was Joyce Godenzi, born to an Australian father and Chinese mother. Godenzi was gorgeous, with wide-set eyes and curly hair, a totally different aesthetic than all the other contestants. Hong Kong was obsessed with her. I was obsessed with her. I practiced walking like her. I threw a shawl around my shoulders, pretending it was the Miss Hong Kong cape that’s presented to the winner when she’s crowned. I clutched a soup ladle in both hands, imagining it was the diamond scepter that Miss Hong Kong carried around on her victory lap. I worked on my smile in the mirror, hoping to achieve a combination of sweetness and whatever my idea of intrigue was at the time.

My biggest concern in previous years had been the question-and-answer section. I worried that my Chinese answers wouldn’t be good enough, since English was my first language and I couldn’t read or write in Chinese. But Joyce took care of that. Joyce’s Chinese wasn’t great either, and all the aunties talked about how this was an advantage because being a foreign-raised candidate was considered exotic.

That afternoon, Ma’s sister was on her way to get her hair done. Ma wanted me out of the way for a while so she told

me to tag along. One of the other stylists at the salon had extra time and ended up curling my hair into ringlets, just like Joyce Godenzi (sort of). When we returned to Grandmother’s, all the mah-jong aunties, and Grandmother too, went bananas over how pretty I looked. They said I was so pretty, I could enter the Miss Hong Kong pageant in a few years. This made my life . . . for about thirty seconds. Until the Squawking Chicken weighed in: “You’re not pretty enough to be Miss Hong Kong.

I

could have been Miss Hong Kong. But Miss Hong Kong is a whore.”

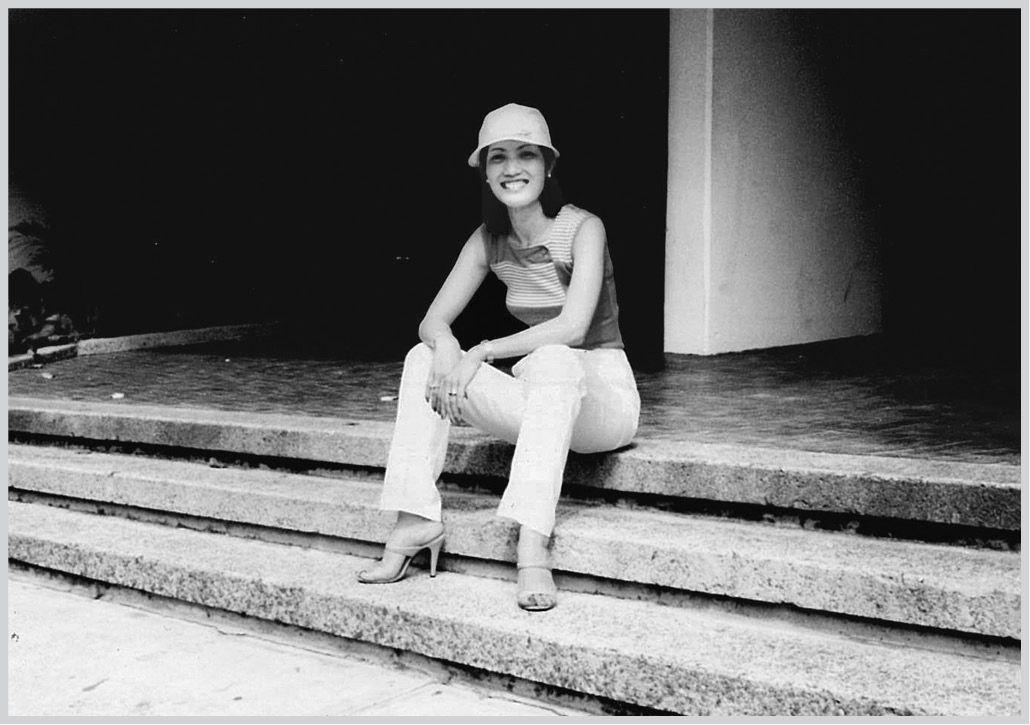

It’s true. Ma was a first-class beauty. I’ve seen the photos—because she shows them to me all the time. While I do resemble her, I’m also half my father, and she reminds me of this all the time too. “It’s too bad you got your stocky body and thick legs from your dad’s side.”

All the aunties reacted like you’re probably reacting right now. How could she say that to a little girl? Let her dream. But for Ma, dreaming was the problem. “Dream? Stop putting dreams in her head. You think I bust my ass raising a daughter just so she could be a beauty pageant whore?”

Most people in Hong Kong believe that the Hong Kong entertainment system is corrupt. And many people believed that Miss Hong Kongs were just glorified escorts for the rich old men who ran the industry. The following year a public uproar broke out when the winner was revealed to

be someone people considered inadequate (she was pretty average-looking and short), and their suspicions seemed to be confirmed when she started dating the geriatric chairman of the network.

So it’s not that Ma meant to be cruel when she told me that I could never be Miss Hong Kong. She had her reasons. First, obviously, she didn’t want me sleeping my way to success. But being “beautiful” also wasn’t an attribute she considered to be important in my case. Or, for that matter, all that useful. From her personal experience, beauty, her beauty, didn’t fix anything and it didn’t make anything either. In Ma’s mind, being beautiful only caused her to be exploited by her parents, and their neglect caused her to be violated as a young girl, and, later, resulted in her being dependent on men—first my father and then my stepfather.

I met him for the first time when Ma finally sent for me to spend the summer with her in Hong Kong a year after she and Dad broke up. I was seven. By this point, I was afraid to leave Dad. I was afraid to get on the plane by myself as an Unaccompanied Minor. But I was more afraid of who I would encounter on the other side.

A gorgeous young woman met me in the airport arrivals area. Her hair was parted in the middle, hanging down each shoulder, held back by jeweled clips on either side. This was not the tired, harried woman who worked two jobs that I

remembered. She lifted a multi-ring adorned hand. And her long red nails beckoned me forward. A glimmer of recognition. And then . . . the voice. “ELAINE!” The Squawking Chicken. My mother. I was claimed. “This is Uncle.”

Ma introduced me to an older man standing next to her with benevolent eyes and a goofy expression. He had no hair and wore glasses. He was tall, taller than Dad, with a soft belly and a round face, the kind of face that ate well, drank well and never worried. Uncle tried to hug me. I resisted. He laughed, a kind laugh, and patted me on the head. “We’re going to have a great summer,” he told me. Then he led us to the car and drove us home, only he didn’t leave. Uncle came inside too. And Uncle stayed. In Ma’s bedroom.

He was an executive with an oil and gas company. When he went to work, Ma played mah-jong with the old crew. He indulged my mother’s whims. He was generous with my greedy grandmother. He loaned money to her siblings. He didn’t mind when Ma invited her mah-jong friends over for all-night sessions. He didn’t shut himself in the TV room and smoke cigarettes, sulking about money, sulking about life’s injustices. Instead, Uncle offered to go out for late-night takeout. Uncle offered to do everything. And he never seemed bothered when people teased him that Ma ran his life.

Ma met Uncle before she married Dad, while she was working in the smuggling trade, shipping Western goods into Communist China. He was almost forty years old while she was only twenty. He pursued her but she wasn’t interested. Shortly after she returned to Hong Kong, they ran into each other again. She was haggard and gaunt. She was sick all the time—the bitter unhappiness of the last few years had taken its toll on her body. She locked herself in a dark room at Grandmother’s house, barely eating, trying to figure out her next steps. Uncle came to visit—bringing healing herbal teas and soups, offering to take the entire family out for dinner, offering to take Ma to the doctor. Grandmother was quickly charmed. She encouraged Ma to go out with him. She practically pushed Ma out the door. Eventually,

Uncle wore her down. He had no expectations. He just wanted to make her happy. He just wanted to look after her. He just wanted to make it easy for her.

“Easy” was the magic word. It had never been easy for Ma. She was exhausted. She was twenty-nine years old and she was tired of rebuilding her life from scratch. Disillusioned by the romanticism of youth, betrayed by the lure of idealistic love, with no assets and no opportunity, with Uncle she wouldn’t have to start from nothing, and this was a proposition she couldn’t afford to walk away from. The Squawking Chicken was nothing if not pragmatic.

Ma was honest with Uncle. She told him that she would always love Dad. She told him that she didn’t know if she could ever love him the way she loved Dad. But she promised him she would be loyal to him. She promised him she would be a good wife. She became a great asset to him professionally. She helped him navigate tricky business relationships, advising him on how to diplomatically advance through the company, cautioning him about potential enemies, encouraging him in areas where he could benefit, politically and financially. She accompanied him on business trips around Asia, a lively, pretty accessory, delighting his associates and partners. She looked after his elderly parents, supervising funeral arrangements for his mother when he

was too overcome by grief to manage. He grew more and more successful with Ma at his side. And he rewarded her with luxurious gifts, trips and, most importantly, by being a wonderful stepfather to me. For a decade they were a formidable couple.

Ma, who trusted very few people, even family, especially family, grew to trust Uncle. Perhaps more than she ever trusted anyone. But over time, Uncle grew to realize that although Ma held up her end of the bargain, no matter how devoted she was to him, no matter the peaceful contentment of their life together, he would never be her One True Love. This began to eat away at him.

When I was sixteen, ten years after they hooked up, Ma found out that Uncle had been spending time with another woman. Ma first heard it from the neighbors, who casually mentioned that they’d seen a mystery woman coming in and out of the house. Then the housekeeper, Leticia, confirmed that Uncle had a female “friend” over quite often when Ma was at mah-jong. Leticia revealed to Ma that she busted Uncle on several occasions and that he’d begged her not to say anything. Ma immediately checked Uncle’s passport. She realized that when he said he was on a business trip to Singapore, he had really been in Hawaii with his lady friend. She then checked the bank account. Turns out, Uncle had

purchased a new Mercedes. But there was no Mercedes parked in their driveway. He’d been lavishing gifts on the other woman and depleting their savings.

Ma was furious at Uncle, but it wasn’t about the money. What was worse was that, yet again, she’d been disappointed. Once again, she’d

let

herself be disappointed. She’d let herself trust a person who only let her down. And, once again, that disappointment was a result of her powerlessness. Because Ma believed she could never be independent. She had relied on Dad and he let her down. When she relied on her beauty, though it paid off for brief periods of time, it could not be relied on to bring any lasting fulfillment.

Which is why “beautiful” is not an attribute the Squawking Chicken considers to be a compliment worth giving. It’s also why she didn’t think beauty should be relevant to me. Because beauty wouldn’t bring me what she could never achieve: independence. And Miss Hong Kong was not independent.