Lion of Liberty (39 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Another witness to the proceedings put it in simpler terms. “The spell of the magician was upon us.”

47

47

Chapter 16

The Sun Has Set in All Its Glory

Patrick Henry's legal triumphs restored his fame and yielded unprecedented wealth as he accumulated moneyed clients from across the state. Some paid him in choice acreage and afforded him opportunities to acquire vast tracts of rich farmland. By the mid-1790s, he ranked with George Washington and the Lees as one of Virginia's greatest landowners, with direct ownership in more than 100,000 acres and indirect ownership of 15 million more. Among his properties under cultivation, he could count three productive plantations with nearly 25,000 acres in Virginia, 10,000 acres that he leased out in Kentucky, and 23,000 acres in western North Carolina. He also received rents from farms and plantations that he owned in twelve counties, stretching from Chesapeake Bay to the Blue Ridge Mountains. He owned at least 100 slaves, close to 300 cattle producing milk and meat, flocks of sheep for wool, hogs for more meat, and horses to work the fields, pull wagons, or ride to hunt.

“I believe . . . he was better pleased to be flattered as to his wealth than as to his great talents,” Spencer Roane recalled. “He seemed proud of the goodness of his lands and, I believe, wished to be thought wealthy. I have thought indeed that he was too much attached to property. This I have accounted for by reflecting that he had long been under narrow and difficult circumstances from which he was at length happily relieved.”

1

1

In addition to his lands under cultivation, Henry was a successful speculator, buying thousands of acres in the western and northwestern parts of Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and other parts of the frontier, then reselling them in small parcels to would-be settlers. With ratification of the Constitution, however, the character of some of his land speculations began to change. As he warned Richard Henry Lee, ratification had provoked North Carolina and large sections of the west to entertain secession. Although he now opposed all talk of secession, he nonetheless hedged against the possibility by snapping up lands in secession-prone areasâat the bend of the Tennessee River in northern Georgia, just south of the North Carolina line, for example, and, much later, 6,000 acres in North Carolina proper. Henry also joined other investors in forming the Virginia Yazoo Land Company, one of three Yazoo Land Companies in South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, to which the governor sold an astonishing 35 million acres in the western Yazoo River area of Georgia for an even more astonishing price of $500,000, or one and a half cents an acre. Yazoo Company lands stretched across almost all of present-day Alabama and Mississippi to the Mississippi River where the city of Memphis now standsâand where Henry's partners hoped to secede from the United States and found a new and independent sovereign state.

2

Henry and his partners actually cut a better deal than investors in the other Yazoo companies.

2

Henry and his partners actually cut a better deal than investors in the other Yazoo companies.

“I congratulate you on the purchase you have made in Georgia,” wrote Theodore Bland, one of Virginia's Antifederalists in the House of Representatives. “I hope [it] will turn out to your most sanguine expectations and be not only a provision for your family, but an asylum from tyranny whenever it may arise or become oppressive to that freedom which I know you so highly prize, and for which you have been so long a firm and unshaken advocate.”

3

The seeds of secession and civil war were now firmly rooted in much of the South.

3

The seeds of secession and civil war were now firmly rooted in much of the South.

From the first, however, Henry's investments in North Carolina and Georgia turned against him. As it turned out, members of the Georgia legislature sought out their own investors and secretly sold them nearly 9 million acres of the same lands the governor had sold to Henry and the Yazoo Land Companies. As the scandal unfolded and threatened to provoke bloodshed, President Washington stepped into the picture and proclaimed

that all the Yazoo Land Company lands belonged to the Creek Indians under an earlier treaty, and, in 1791, he signed a new treaty reconfirming their title to almost all Yazoo lands, including the lands Henry had purchased. Henry was furious, but helpless.

that all the Yazoo Land Company lands belonged to the Creek Indians under an earlier treaty, and, in 1791, he signed a new treaty reconfirming their title to almost all Yazoo lands, including the lands Henry had purchased. Henry was furious, but helpless.

“I need not . . . point out to you the danger consequent to all landed property in the Union from an acquiescence in such assumption of power,” he raged at Georgia's governor. Citing his preratification prophecy that the Constitution gave Congress tyrannical powers, he warned that “if Congress may of right forbid purchases from the Indians of territory included in the charter limits of your state . . . it is not easy to prove that any individual citizen has an indefeasible right to any land claimed under a state patent.”

4

4

In the months that followed, southern newspapers charged that the Virginia Yazoo Companies had bribed Georgia's governor and many of its legislators to acquire their lands. Georgia voters responded by ousting the governor and most of the legislature. A new, reform-minded legislature repudiated the Yazoo deal and burned all records relating to it in hopes of destroying evidence that could be used in subsequent legal proceedings by Yazoo shareholders to recoup their holdings. Henry lost his entire investment.

5

5

The loss of his Yazoo Land Company holdings climaxed a year of financial reverses for Henry and many other southern investors at the hands of the new Federal Governmentâreverses that Henry had predicted in his angry outbursts at the Virginia ratification convention two years earlier. The first and costliest came in January 1790, when Federalist Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton reported that federal government debts had ballooned to almost $60 millionâ$44 million in domestic debts and $12 million foreign. With no specie to pay the debts, market values of outstanding government debt certificates plunged so low that the government could no longer borrow to meet current expenses. To restore government credit, Hamilton asked Congress to recall all outstanding debt certificates at parâat their face valueâand pay for them with a combination of new government bonds and certificates of title to government wilderness lands in the West. The government would, in other words, back the new bonds with “real” estate of unquestioned value.

Hamilton's plan provoked outrage across the nation. Throughout the Revolutionary War and Confederation years, the government had paid

soldiers, merchants, farmers, craftsmen, and other citizens with government certificates, which they, in turn, had to resell to bankers and speculators for whatever they could getânever more than 75 percent of face value and sometimes less than 15 percent.

soldiers, merchants, farmers, craftsmen, and other citizens with government certificates, which they, in turn, had to resell to bankers and speculators for whatever they could getânever more than 75 percent of face value and sometimes less than 15 percent.

Hamilton's proposal to recall certificates at face value promised untold riches for the bankers and speculators who had exploited American veterans when they were struggling to survive. Adding to the outrage was a second Hamilton scheme for the federal government to assume $25 million in state war debtsâand pay those debts with proceeds from a federal tax on whiskeyâthe most popular beverage in America. Americans consumed whiskey for both pleasure and medicinal purposes, and, in a barter society, they used various sized jugs to buy staples and other dry goods at market. In the West, the tax threatened every farmer's earnings. With no wagon roads across the rugged Appalachians, farmers could only market their grain by converting it to whiskey, which they could carry in jugs by mule or packhorse along the narrow mountain trails. A whiskey tax was as abhorrent to Americans in 1790 as Britain's tea tax had been to Bostonians in 1773, when they staged the Boston Tea Party.

Southern states were irateâespecially Virginia, which had already repaid most of its own war debts and felt no obligation to help repay debts accumulated by profligate states such as Massachusetts. Even Federalists, including Virginia Governor Henry Lee, reviled Hamilton and the northern Federalists. Recalling Patrick Henry's words at the Virginia ratification convention, Lee raged at Madison, who was still a member of the House, that disunion would be preferable to domination and economic exploitation by “an insolent northern majority.

“Henry is considered a prophet,” Lee growled. “His predictions are daily verified. His declarations with respect to the divisions of interests which would exist under the Constitution and predominate on all the doings of government already have been undeniably proved. But we are committed and we cannot be relieved, I fear, only by disunion.”

6

6

Despite higher taxes and losses from his Yazoo Land Company investment, Patrick Henry's profits from other land speculations, from his lands under cultivation, and from his law practice left him with abundant

wealth in his last years. Nor did the Yazoo scandal diminish the adulation of his countrymen, for whom he remained a legendary patriot whom they flocked to see and hear whenever he tried a case. More often than not, he gave them a show to rememberâas in the case of a young man on trial for abduction of a minor after eloping with his underaged girlfriend. The young man had had the foresight to consult Henry before the “kidnapping.” Henry told him to ask the young lady to ride to their rendezvous on her father's horse and let her husband-to-be mount behind her for the ride to the marriage ceremony. When the case came to trial, Henry put her on the witness stand and asked whether her husband had abducted her. She answered truthfully: “No, sir. I ran away with him.” After the roars of laughter died down, the judge dismissed the case.

wealth in his last years. Nor did the Yazoo scandal diminish the adulation of his countrymen, for whom he remained a legendary patriot whom they flocked to see and hear whenever he tried a case. More often than not, he gave them a show to rememberâas in the case of a young man on trial for abduction of a minor after eloping with his underaged girlfriend. The young man had had the foresight to consult Henry before the “kidnapping.” Henry told him to ask the young lady to ride to their rendezvous on her father's horse and let her husband-to-be mount behind her for the ride to the marriage ceremony. When the case came to trial, Henry put her on the witness stand and asked whether her husband had abducted her. She answered truthfully: “No, sir. I ran away with him.” After the roars of laughter died down, the judge dismissed the case.

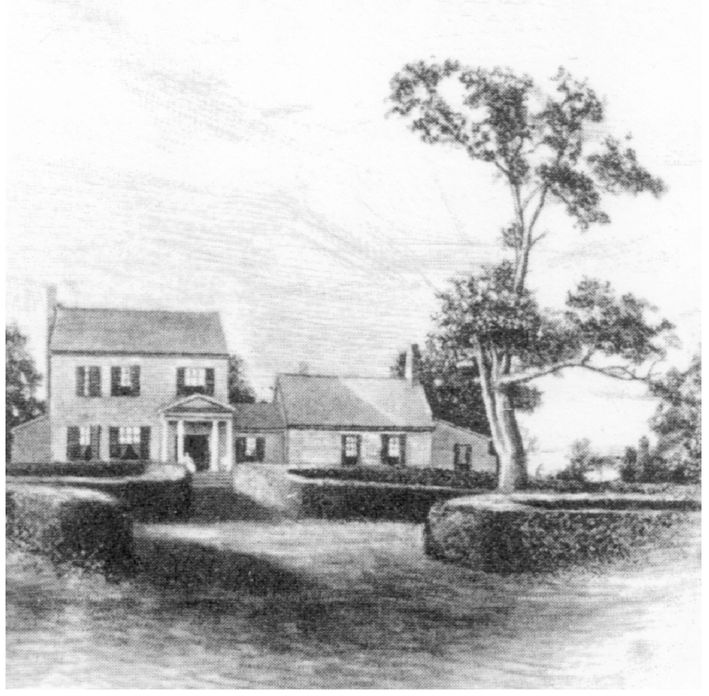

In 1794, the isolation of Long Island proved “so much as to disgust” Dolly that Henry bought another estate about twenty miles to the eastâstill on the Staunton River, but just across the Campbell County line in Charlotte County, where the Henrys could lead a richer social life. Named Red Hill for the color of its soil, their new homeâhis twelfth over the course of his lifeâhad four rooms, with magnificent views of the valley. Before they moved, Dorothea gave birth to their eighth surviving child and fourth son, whom they named Edward, after Henry's late son “Neddy.”

Only fifty-eight, but ailing, Henry finally retired from the law to live at home full time and “see after my little flock and the management of my plantations.” Despite the move to Red Hill, he kept the profitable Long Island plantation and, indeed, moved the family back to its healthier climate each year during the “sickly season” when mosquitoes swarmed across most of the bottom land at Red Hill. Red Hill nonetheless proved to be his most profitable property, with nearly 3,000 acres, on which 69 slaves produced more than 20,000 pounds of tobacco annually and tended nearly 130 head of cattle, 186 hogs, 38 sheep, 5 yoke of oxen, and 19 horses.

7

Near the kitchen garden stood an apple and a peach orchard, along with fig trees. Like his Long Island farm, Red Hill was on the Staunton River, where flat-bottomed “bateaux” could carry his tobacco and grains to market. As he had done at his previous homes, he built a separate, freestanding law office from which he not only practiced law but trained his son, Patrick Jr., his

two nephews Johnny Christian and Nathaniel West Dandridge II, and his grandson Patrick Henry Fontaine for the law.

7

Near the kitchen garden stood an apple and a peach orchard, along with fig trees. Like his Long Island farm, Red Hill was on the Staunton River, where flat-bottomed “bateaux” could carry his tobacco and grains to market. As he had done at his previous homes, he built a separate, freestanding law office from which he not only practiced law but trained his son, Patrick Jr., his

two nephews Johnny Christian and Nathaniel West Dandridge II, and his grandson Patrick Henry Fontaine for the law.

Patrick Henry's home at “Red Hill,” near Brookneal, in Charlotte County, Virginia, where he spent his retirement years and died on June 6, 1799. He is buried on the property alongside his second wife, Dorothea.

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PRINT)

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PRINT)

As Henry had predicted at the Virginia ratification convention, Federalist Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton lured the Federalist-dominated Congress into using its unrestricted powers under the “necessary and proper” clause of the Constitution to expand the scope of the whiskey tax

to include stills. The tax proved a disproportionately heavy burden on farmers west of the Appalachian Mountains after the Spanish closure of the Mississippi River to American navigation left them unable to ship their grain to market in New Orleans. Farmers could only market their grain by converting it to whiskey. The tax on stills, therefore, threatened every western farmer's earnings.

to include stills. The tax proved a disproportionately heavy burden on farmers west of the Appalachian Mountains after the Spanish closure of the Mississippi River to American navigation left them unable to ship their grain to market in New Orleans. Farmers could only market their grain by converting it to whiskey. The tax on stills, therefore, threatened every western farmer's earnings.

Other books

Teasing Jonathan by Amber Kell

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction: 23rd Annual Collection by Gardner Dozois

The Botox Diaries by Schnurnberger, Lynn, Janice Kaplan

What God Has For Me by Pat Simmons

Smooth Operator by Emery, Lynn

A World of My Own by Graham Greene

Dark Moon Defender (Twelve Houses) by Shinn, Sharon

Brothers in Arms by Lois McMaster Bujold

Legacy of Silence by Belva Plain

Guardian's Beloved Mate (Song of the Sídhí Series #4) by Cooper, Jodie B