Lion of Liberty (29 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

As one of the primary organizers of the convention, however, James Madison presented an optimistic front: “There never was an assembly of men,” he boasted, “who were more devoted . . . to the object of devising and proposing a constitutional system which would . . . best secure the permanent liberty and happiness of their country.”

8

Henry mocked Madison by asserting that there had never been an assembly of men who were more devoted to preserving and enhancing their own wealth. For as Henry noted, the delegates at Philadelphia were the wealthiest, most powerful and best educated men in America. None represented the less affluent farm regions in the western parts of the twelve states. Twenty-one held college degrees; twenty-nine were lawyers or judges, and nearly all held political offices or had served on Revolutionary War committees. With Washington presiding, they would sit five to six hours a day, six days a week, from May 25 until September 17, 1787, except for a nine-day adjournment between July 29 and August 6, to let a committee arrange and edit the resolutions into a readable draft constitution.

8

Henry mocked Madison by asserting that there had never been an assembly of men who were more devoted to preserving and enhancing their own wealth. For as Henry noted, the delegates at Philadelphia were the wealthiest, most powerful and best educated men in America. None represented the less affluent farm regions in the western parts of the twelve states. Twenty-one held college degrees; twenty-nine were lawyers or judges, and nearly all held political offices or had served on Revolutionary War committees. With Washington presiding, they would sit five to six hours a day, six days a week, from May 25 until September 17, 1787, except for a nine-day adjournment between July 29 and August 6, to let a committee arrange and edit the resolutions into a readable draft constitution.

Convention rules gave each state one vote, determined by a majority of delegates from that state. Of all rules adopted, the two most important were the secrecy rule, to protect delegates from political reprisals for speaking or voting their consciences or private interests, and a rule allowing delegates to reconsider previous issues and change their votes. Although the convention allowed James Madison to take notes of the proceedings, he would keep the notes secret for his entire life. Among other reasons, he sought to prevent political enemies of the delegatesâand the Constitutionâfrom quoting elements of speeches out of context. Madison outlived all other delegates, surviving until 1836, forty-eight years after the convention.

Recognizing both the stature of Washington as the most unifying figure in the Confederation and the status of Virginia as its most powerful

state, delegates elected him president. Although he did not participate in debate, at least three dozen of the fifty-five delegates had served under him in the Revolutionary War. All knew his views, which became paramount in the proceedings. Indeed, he had sent all the governors and other state leaders an outline of the kind of government he favored. It came as no surprise then that, after the initial election of officers and adoption of rules, Washington recognized immediately Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph to present the “Virginia Plan” of government, which fleshed out Washington's own outline for a new national government.

state, delegates elected him president. Although he did not participate in debate, at least three dozen of the fifty-five delegates had served under him in the Revolutionary War. All knew his views, which became paramount in the proceedings. Indeed, he had sent all the governors and other state leaders an outline of the kind of government he favored. It came as no surprise then that, after the initial election of officers and adoption of rules, Washington recognized immediately Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph to present the “Virginia Plan” of government, which fleshed out Washington's own outline for a new national government.

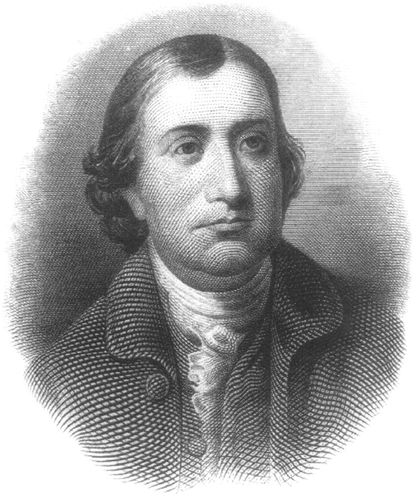

Born to a long line of English noblemen who had served as king's attorneys, Edmund Randolph had attended the College of William and Mary and studied law under his father, who fled to England with his close friend Lord Dunmore when the Revolution began. Twenty-two years old at the time, Edmund enlisted in the Continental Army, becoming an aide to Washington before returning to Virginia as State Attorney General, then mayor of Williamsburg until he succeeded Henry as Governor. After discussions with Henry, Randolph had gone to Philadelphia agreeing to seek only minor revisions of the Articles of Confederation, but, overwhelmed by the powerful personalities in his delegation, he reluctantly agreed, as governor of his state, to present the far-reaching Virginia Plan favored by Washington.

Instead of “revising the Articles of Confederation,” as instructed by Congress, the Virginia Plan called for scrapping the Articles and creating a new form of government. It was nothing short of a bloodless coup d'étatâa second American revolution without firing a shot.

9

Knowing the plan would meet with opposition, but unwilling to split with Washington, Randolph sought to retain links to all political factions and “expressed his regret that it should fall to him . . . to open the great subject of their mission. But,” he said, “his colleagues had imposed this task on him.”

10

9

Knowing the plan would meet with opposition, but unwilling to split with Washington, Randolph sought to retain links to all political factions and “expressed his regret that it should fall to him . . . to open the great subject of their mission. But,” he said, “his colleagues had imposed this task on him.”

10

The Virginia Plan proposed fifteen resolutions which, among other things, called for replacing the unicameral Confederation Congress with “a

national

government consisting of a

supreme

Legislative, Executive and Judiciary.” The national legislature would have an upper and lower house and be the most powerful branch of government, with sole power to elect

both the executive and the judges of a supreme court. The people would elect the lower house, with the number of delegates proportionate to the number of “free inhabitants” in each state. The Lower house would elect members of the upper house from nominees chosen by the legislatures of each state. Most astonishing, the new Congress would have the very powers that Henry despised most about the British governmentânamely, “to negative all laws passed by the several states . . . and to call forth the force of the Union against any member of the Union failing to fulfill its duty under the articles thereof.”

11

national

government consisting of a

supreme

Legislative, Executive and Judiciary.” The national legislature would have an upper and lower house and be the most powerful branch of government, with sole power to elect

both the executive and the judges of a supreme court. The people would elect the lower house, with the number of delegates proportionate to the number of “free inhabitants” in each state. The Lower house would elect members of the upper house from nominees chosen by the legislatures of each state. Most astonishing, the new Congress would have the very powers that Henry despised most about the British governmentânamely, “to negative all laws passed by the several states . . . and to call forth the force of the Union against any member of the Union failing to fulfill its duty under the articles thereof.”

11

Governor Edmund Randolph of Virginia refused to endorse and sign the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphiaâonly to change his position at the Virginia ratification convention the following year and vote for ratification. After George Washington won election as President he appointed Randolph the first U.S. Attorney General.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The Virginia Plan was nothing less than Washington's revenge for congressional failure to provide him and his troops with adequate funding

during the Revolutionary War. Under the Virginia Plan, the laws of Congress would be supreme and Congress would be free to use military force to enforce them. Washington believed that “the primary cause of all our disorders lies in the different state governments, and in the . . . incompatibility in the laws of different states and disrespect to those of the general government.” The result, he declared, had left “this great country weak, inefficient and disgraceful . . . almost to the final dissolution of it. ...”

12

during the Revolutionary War. Under the Virginia Plan, the laws of Congress would be supreme and Congress would be free to use military force to enforce them. Washington believed that “the primary cause of all our disorders lies in the different state governments, and in the . . . incompatibility in the laws of different states and disrespect to those of the general government.” The result, he declared, had left “this great country weak, inefficient and disgraceful . . . almost to the final dissolution of it. ...”

12

Delegates responded to the Virginia Plan with shocked silence. In effect, the plan called for the overthrow of the legally constituted American government. It would not only create an entirely new form of government, it would strip the states of their sovereignty. Outraged delegates from North and South denounced the plan, calling its presentation out of order and a violation of the mandate of Congress limiting the convention's role to

revising

the existing Articles of Confederation. “The act of Congress recommending the Convention,” said South Carolina's Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a Revolutionary War hero and prominent attorney, did not “authorize a discussion of a system founded on different principles” from the Federal Constitution [Articles of Confederation].” His cousin Charles Pinckneyâa young Charleston attorneyâdemanded to know whether Randolph's plan was meant “to abolish state government altogether.”

13

revising

the existing Articles of Confederation. “The act of Congress recommending the Convention,” said South Carolina's Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a Revolutionary War hero and prominent attorney, did not “authorize a discussion of a system founded on different principles” from the Federal Constitution [Articles of Confederation].” His cousin Charles Pinckneyâa young Charleston attorneyâdemanded to know whether Randolph's plan was meant “to abolish state government altogether.”

13

In the days that followed, all semblances of collegiality disappeared, with southerners demanding that slaves (who had no vote and went uncounted when apportioning representatives in state assemblies) be counted in determining proportionate representation in the lower house. Small states rejected the concept of proportionate representation, arguing that two or three states with the largest populationsâVirginia, Pennsylvania, and Massachusettsâcould dominate the entire Union. They argued for perpetuation of the one-state, one-vote rule of the Confederation Congress. Delegates from large states countered that the one-state, one-vote rule would allow a handful of small states with only a minority of the nation's population to dictate to the majority.

As the debate raged, delegates grew increasingly mean-spirited, with some northerners even mocking the accents of delegates from the deep South, to which southerners countered by pretending they could not understand Boston's delegates and asking them to repeat themselves. When

Pennsylvania's abolitionists demanded an end to slavery, South Carolina's delegates threatened to walk out, and early in July, two of New York's three delegates did leaveâstomping out in an angry protest against attempts to crush state sovereignty. Faced with a breakup of the Conventionâand the Confederation itselfâcalmer heads prevailed, and the remaining delegates went to work to find compromises for their outstanding disputes. In the end they decided on proportionate representation in the lower house and state parity in the upper house. They gave the lower house sole power to originate appropriations legislation, thus keeping control over the nation's moneyâand, therefore, all government activitiesâin the hands of the electorate. As for slaves, northerners objected to counting nonvoting slaves in the population because it would give the owners of Virginia's huge Tidewater plantations inordinate political powers. George Mason, whose plantation was almost adjacent to Washington's Mount Vernon, argued that the inclusion of slaves in the population count would give them an indirect influence in legislation and that “such a system would provide no less carefully for the rights and happiness of the lowest than of the highest orders of citizens.

14

As southerners cheered his disingenuous position, Connecticut's Oliver Ellsworth responded tartly, “Mr. Mason has himself about three hundred slaves and lives in Virginia, where it is found by prudent management they can breed and raise slaves faster than they want for their own use and could supply the deficiency in Georgia and South Carolina.”

15

To prevent a walkout by southerners, the convention compromised by allotting lower house votes based on the total free population of each state and three-fifths of the slave population. Spurred by messages from Patrick Henry, the South demanded another concession from the North, making it necessary for the upper house to confirm foreign treaties by a two-thirds vote instead of a simple majority. Southerners had not forgotten how northern states in Congress had almost ceded Mississippi River navigation rights to Spain two years earlier. Only the two-thirds requirement of the Confederation Congress had prevented the treaty from becoming law.

Pennsylvania's abolitionists demanded an end to slavery, South Carolina's delegates threatened to walk out, and early in July, two of New York's three delegates did leaveâstomping out in an angry protest against attempts to crush state sovereignty. Faced with a breakup of the Conventionâand the Confederation itselfâcalmer heads prevailed, and the remaining delegates went to work to find compromises for their outstanding disputes. In the end they decided on proportionate representation in the lower house and state parity in the upper house. They gave the lower house sole power to originate appropriations legislation, thus keeping control over the nation's moneyâand, therefore, all government activitiesâin the hands of the electorate. As for slaves, northerners objected to counting nonvoting slaves in the population because it would give the owners of Virginia's huge Tidewater plantations inordinate political powers. George Mason, whose plantation was almost adjacent to Washington's Mount Vernon, argued that the inclusion of slaves in the population count would give them an indirect influence in legislation and that “such a system would provide no less carefully for the rights and happiness of the lowest than of the highest orders of citizens.

14

As southerners cheered his disingenuous position, Connecticut's Oliver Ellsworth responded tartly, “Mr. Mason has himself about three hundred slaves and lives in Virginia, where it is found by prudent management they can breed and raise slaves faster than they want for their own use and could supply the deficiency in Georgia and South Carolina.”

15

To prevent a walkout by southerners, the convention compromised by allotting lower house votes based on the total free population of each state and three-fifths of the slave population. Spurred by messages from Patrick Henry, the South demanded another concession from the North, making it necessary for the upper house to confirm foreign treaties by a two-thirds vote instead of a simple majority. Southerners had not forgotten how northern states in Congress had almost ceded Mississippi River navigation rights to Spain two years earlier. Only the two-thirds requirement of the Confederation Congress had prevented the treaty from becoming law.

With each passing day, delegates found something new to dispute, until Washington lost all patience and collared delegates outside the meeting hallâat the City Tavern and at dinners in private homesâand demanded that they reach a compromise. As he later put it, “Every state has some objection.

That which is most pleasing to one is obnoxious to another and vice versa. If then the union of the whole is a desirable object, the parts which compose it must yield a little in order to accomplish it.” The reading of a statement by the aging Benjamin Franklin made the same point more humorously. The impasse, he said, reminded him of the Anglican leader who explained to the Pope, that “the only difference between our churches lies in the certainty of their doctrinesâthat the Church of Rome is infallible and the Church of England is never in the wrong.”

16

That which is most pleasing to one is obnoxious to another and vice versa. If then the union of the whole is a desirable object, the parts which compose it must yield a little in order to accomplish it.” The reading of a statement by the aging Benjamin Franklin made the same point more humorously. The impasse, he said, reminded him of the Anglican leader who explained to the Pope, that “the only difference between our churches lies in the certainty of their doctrinesâthat the Church of Rome is infallible and the Church of England is never in the wrong.”

16

On July 29, the Convention recessed to allow a committee to combine the resolutions that had been approved into a cohesive finished document. When the convention reconvened on August 6, South Carolina's John Rutledgeâanother war hero and lawyerâread it aloud, beginning with the preamble:

“We the people of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut [he read the names of all thirteen states] . . . do hereby declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government ourselves and our posterity.”

17

The language put some delegates to sleep, but aroused others to renewed debate, with a core group of rabid abolitionists from the Quaker state of Pennsylvania reiterating demands for an end to the slave trade. South Carolina threatened to reject the document “if it prohibits the slave trade . . . If the states be all left at liberty on the subject, South Carolina may perhaps by degrees do of herself what is wished.”

18

To keep the deep South in the Union, the North agreed not to interfere with the importation of slaves for twenty years, but almost every delegate found other elements of the Constitution unacceptable, with some predicting civil war when it went to the state legislatures for ratification. The delegates found something to debate until the very last dayâmost importantly, George Mason's demands for a bill of rights to guarantee individual rights and limits on national government powers.

17

The language put some delegates to sleep, but aroused others to renewed debate, with a core group of rabid abolitionists from the Quaker state of Pennsylvania reiterating demands for an end to the slave trade. South Carolina threatened to reject the document “if it prohibits the slave trade . . . If the states be all left at liberty on the subject, South Carolina may perhaps by degrees do of herself what is wished.”

18

To keep the deep South in the Union, the North agreed not to interfere with the importation of slaves for twenty years, but almost every delegate found other elements of the Constitution unacceptable, with some predicting civil war when it went to the state legislatures for ratification. The delegates found something to debate until the very last dayâmost importantly, George Mason's demands for a bill of rights to guarantee individual rights and limits on national government powers.

In the end, Washington brought the convention to heel, warning, “There are seeds of discontent in every part of the Union ready to produce disorders if . . . the present convention should not be able to devise a more vigorous and energetic government.”

19

19

On September 12, a “Committee on Stile,” for which Pennsylvania's Gouverneur Morris had exercised his brilliant writing skills, presented the

convention with copies of the final draft of the Constitution, linking it through its preamble to the Declaration of Independence.

convention with copies of the final draft of the Constitution, linking it through its preamble to the Declaration of Independence.

WE, THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES, IN ORDER TO FORM a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Other books

Notorious by Karen Erickson

Forbidden Paths by Belden, P. J.

Blood Rain - 7 by Michael Dibdin

The Accident by Chris Pavone

Just a Little Reminder by Tracie Puckett

Don’t Talk to Strangers: A Novel by Amanda Kyle Williams

Coup De Grâce by Lani Lynn Vale

Jack, Knave and Fool by Bruce Alexander

Daughter of Necessity by Marie Brennan

A Mate for the Beta: by E A Price