Lion of Liberty (15 page)

Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

After signing the document, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and George Washington saddled up for the long ride home. John Adams approached them to say good-bye and showed them a letter he had received from the mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts, saying, “We must fight if we can't otherwise rid ourselves of British taxation . . . enacted for us by the British parliament.”

“By God,” Henry interrupted, “I am of that man's mind. We must fight.”

Richard Henry Lee disagreed: “We shall infallibly carry all our points; you will be completely relieved; all the offensive acts will be repealed; the army and fleet will be recalled, and Britain will give up her foolish project.”

“Only Washington was in doubt,” Adams noted.

18

18

When Henry arrived home, his Hanover County neighbors asked him the prospects of reconciliation with Britain. Already furious at the intrusions of the British government in his life, Henry asserted that Britain “will drive us to extremitiesâno accommodation will take placeâhostilities will soon commenceâand a desperate and bloody touch it will be.”

19

In his heart and soul, Patrick Henry had already declared war.

19

In his heart and soul, Patrick Henry had already declared war.

Chapter 7

“Give Me Liberty ...”

Virginia was preparing for war when Henry rode home from the First Continental Congress in September 1774. “Every county is now arming a company of men whom they call an independent company,” Royal Governor Lord Dunmore wrote to the secretary of state for the colonies on Christmas Eve. In fact, almost every state was arming or planning to do so. Maryland had resolved two weeks earlier to organize a militia to eliminate the need for protection by regular British troops. Delaware followed suit two weeks later, and in early January, George Washington took command of the hundred-man Fairfax Independent Company in AlexandriaâVirginia's first such force.

When Henry reached Scotchtown after the Continental Congress, he learned that his wife had attempted suicide during his absence and had deteriorated into deep depression. His oldest daughter, Martha, and her husband, John Fontaine, who had been caring for the five younger Henry children, had brought the entire brood to Scotchtown for the Christmas holidays in hopes of lifting Sarah Henry's spirits. Henry had little time for his family, however. Stirred by fears of imminent British attack, he rode into Hanover town to call together the men of the county. He “addressed them in a very animated speech, pointing out the necessity of our having recourse to arms in defense of our rights, and recommending in strong

terms that we should immediately form ourselves into a volunteer company.”

1

Abetted by a few jugs of white lightning, Henry's emotional appeal sent the mountain men into a frenzy of patriotic fervor that left them pushing and shoving to volunteer in his company. After they'd finished signing up, they elected him their captain by unanimous vote, and Henry rode home to spend what remained of the Christmas holidays with his family. They proved to be melancholy days indeed. After plunging into an abyss of depression, Sarah Henry died early in the new year.

terms that we should immediately form ourselves into a volunteer company.”

1

Abetted by a few jugs of white lightning, Henry's emotional appeal sent the mountain men into a frenzy of patriotic fervor that left them pushing and shoving to volunteer in his company. After they'd finished signing up, they elected him their captain by unanimous vote, and Henry rode home to spend what remained of the Christmas holidays with his family. They proved to be melancholy days indeed. After plunging into an abyss of depression, Sarah Henry died early in the new year.

After burying his wife, Henry buried himself in nonstop political and military activities, drilling his volunteers and preparing for the Second Virginia Convention. Only six or seven other counties across the colony had managed to raise companies of any consequence. In fact, most Virginians agreed with Richard Henry Lee that the king and Parliament would respond favorably to the Continental Congress petition for redressâmuch as they had responded by repealing most of the Townshend Acts in 1770 in the aftermath of the Boston Massacre.

Indeed, all England seemed to support the American petition. When Parliament reconvened in January 1775, petitions from London, Bristol, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, and almost every other trading city asked for restoration of normal relations with the colonies.

On January 12, however, George III dashed their hopes. After reading the petition of the Continental Congress, he responded with a broad, cynical smile, complimented its eloquence, and laid it aside. A fortnight later, he rejected it and demanded that Parliament halt trade with the colonies, provide army protection for Loyalists, and arrest colonist protesters as traitors. As the House of Commons debated passage of legislation to transform the king's pronouncements into law, Edmund Burke again pleaded with his colleagues to reconsider. “The use of force alone is but temporary,” he protested. “It may subdue for a moment; but it does not remove the necessity of subduing again, and a nation is not governed which is perpetually being conquered.”

2

Parliament relented only slightly after Burke's speech by offering a blanket pardon to repentant rebelsâwith the exception of such “principal Gentlemen who . . . are to be brought over to England . . . for an inquiry . . . into their conduct.” Among them were George Washington,

Patrick Henry, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, and other radicals the government believed were in “a traitorous conspiracy” against a monarch seated by “Divine Providence.” As punishment for such a crime, British law dictated hanging by the neck and “while you are still living your bodies are to be taken down, your bowels torn out . . . your head then cut off, and your bodies divided each into four quarters. ...”

3

2

Parliament relented only slightly after Burke's speech by offering a blanket pardon to repentant rebelsâwith the exception of such “principal Gentlemen who . . . are to be brought over to England . . . for an inquiry . . . into their conduct.” Among them were George Washington,

Patrick Henry, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, and other radicals the government believed were in “a traitorous conspiracy” against a monarch seated by “Divine Providence.” As punishment for such a crime, British law dictated hanging by the neck and “while you are still living your bodies are to be taken down, your bowels torn out . . . your head then cut off, and your bodies divided each into four quarters. ...”

3

Although news had reached America that the king had smiled at the Continental Congress petition, word of his subsequent rejection and Parliament's trade embargo had yet to reach the former burgesses when they called for a Second Virginia Convention. They picked Richmond as their site rather than Williamsburg, where a buildup of British naval strength in nearby waters raised the menace of Lord Dunmore's arresting Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and other Virginia political leaders. A town of only 600 residents and 150 homes, Richmond had no assembly hall, as such. The largest seating area was in St. John's Anglican Church on Richmond Hill, with space in its pews for about 120 people.

On March 20, 1775, the delegates sidled into the pewsâWashington, Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee and other renowned Virginians. Henry took a seat in the third pew on the gospel, or left, side of the church facing the front. Almost all wanted to believe rumors, born of the king's smile, that Parliament would repeal most of the Intolerable Acts and restore calm in America. Every delegate seemed in a good mood as the convention openedâevery delegate but Henry. Confident again in his regional political pond, he reclaimed his Demosthenic airs and “in the sacred place of meeting, launched forth in solemn tones.”

4

He proposed three resolutions, with the first two merely parroting the Maryland resolutions of the previous December: “That a well regulated militia, composed of gentlemen and yeomen, is the natural strength and only security of a free government; that such a militia in this colony would forever render it unnecessary for the mother country to keep among us, for the purpose of our defense, any standing army of mercenary soldiers . . . and would obviate the pretext of taxing us for their support.”

5

4

He proposed three resolutions, with the first two merely parroting the Maryland resolutions of the previous December: “That a well regulated militia, composed of gentlemen and yeomen, is the natural strength and only security of a free government; that such a militia in this colony would forever render it unnecessary for the mother country to keep among us, for the purpose of our defense, any standing army of mercenary soldiers . . . and would obviate the pretext of taxing us for their support.”

5

Henry's third resolution, however, broke new ground with nothing less than a declaration of war: “That this colony be immediately put into

a state of defense, and . . . prepare a plan for embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men, as may be sufficient for that purpose.”

6

Spectators standing at the rear of the church applauded, as Peyton Randolph, the president of the convention, stood at the front trying to bring his “congregation” to order.

a state of defense, and . . . prepare a plan for embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men, as may be sufficient for that purpose.”

6

Spectators standing at the rear of the church applauded, as Peyton Randolph, the president of the convention, stood at the front trying to bring his “congregation” to order.

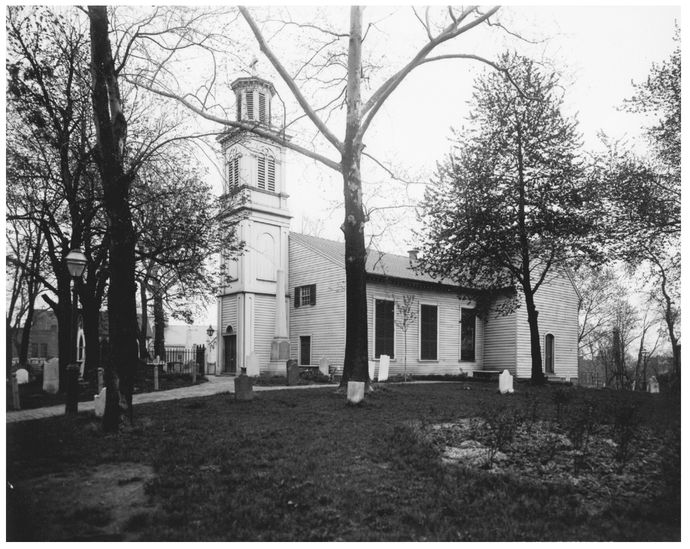

St. John's Church in Richmond, Virginia, where Patrick Henry delivered his stirring speech ending, “Give me liberty, or give me death.”

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Richard Henry Lee immediately seconded Henry, and in the debate that followed, many delegates insisted that peace was imminent and that Henry's resolutions were premature. “Washington was prominent, though silent,” recalled Edmund Randolph, who had chosen to remain in America while his father, a staunch Tory, prepared to return to England. “His [Washington's] looks bespoke . . . a positive concert between him and Henry.”

7

7

When all the delegates had finished expressing their views, Henry stood to speak. A clergyman at the church described the scene:

Henry arose with an unearthly fire burning in his eye . . . this time with a majesty . . . and with all that self-possession by which he was so invariably distinguished . . . the tendons of his neck stood out white and rigid like whipcords. . . .

8

8

Â

Mr. President, it is natural to man to indulge in the illusions of hope. We are apt to shut our eyes against a painful truthâand listen to the song of that siren, till she transforms us into beasts. Is this the part of wise men engaged in a great and arduous struggle for liberty? . . .

Â

Henry paused . . .

Â

I know of no way to judge the future but by the past. And judging by the past, I wish to know what there has been in the conduct of the British ministry for the past ten years to justify the hopes with which these gentlemen have been pleased to solace themselves and the House? Is it that insidious smile with which our petition has been lately received? Trust it not, sir. . . . Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss. Ask yourselves how this gracious reception of our petition comports with those warlike preparations which cover our waters and darken our land. Are fleets and armies necessary to a work of love and reconciliation? . . . Let us not, I beseech you, sir, deceive ourselves longer . . .

Â

Henry's voice rose . . .

Â

We have petitionedâwe have remonstratedâwe have supplicatedâwe have prostrated ourselves before the throne . . . we have been spurned, with contempt from the foot of the throne. There is no longer any room for hope. If we wish to be free . . . we must fight!

I repeat it, sir: We must fight!

9

9

Â

Henry paused again, staring heavenwards at the roof beams of the church. The delegates sat in stunned silence, many believing they had heard a voice as from heaven uttering the words, âWe must fight,' as the doom of Fate . . . He stood silently, as if in prayer. The tension of his listeners building, awaiting an inevitable eruption.

Gentlemen may cry peace, but there is no peace. . . .

Â

His voice grew louder. . . . The walls of the building and all within seemed to shake and rock in its tremendous vibrations. . . .

Â

The war is actually begun! The next gale from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms!

Â

... thunder. . . .

Â

Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it the gentlemen wish? What would they have?

Â

After a solemn pause, he stood . . . like an embodiment of helplessness . . . his form was bowed . . . a condemned galley slave . . . with fetters, awaiting his doom. . . .

Â

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?

Â

He raised his eyes and chained hands toward heaven and prayed . . .

Â

Forbid it, Almighty God!

Â

He then turned toward the timid loyalists . . . quaking at the penalties of treason . . . and bent his form yet nearer to the earth . . . with his hands still crossed . . . he seemed to be weighed down with . . . chains . . . transformed into hopeless . . . humiliation . . . under the iron heel of military despotism. . . .

Â

I know not what course others may take, but as for me . . .

Â

He arose proudly . . . the words hissed through his clenched teeth while his body was thrown back . . . every muscle and tendon was strained against the fetters which bound him, and, with his countenance distorted with agony and rage . . . his arms were hurled apart . . . the links of his chains were scattered

to the winds . . . his countenance radiant . . . he stood erect and defiant . . . the sound of his voice . . . the loud, clear, triumphant notes . . .

to the winds . . . his countenance radiant . . . he stood erect and defiant . . . the sound of his voice . . . the loud, clear, triumphant notes . . .

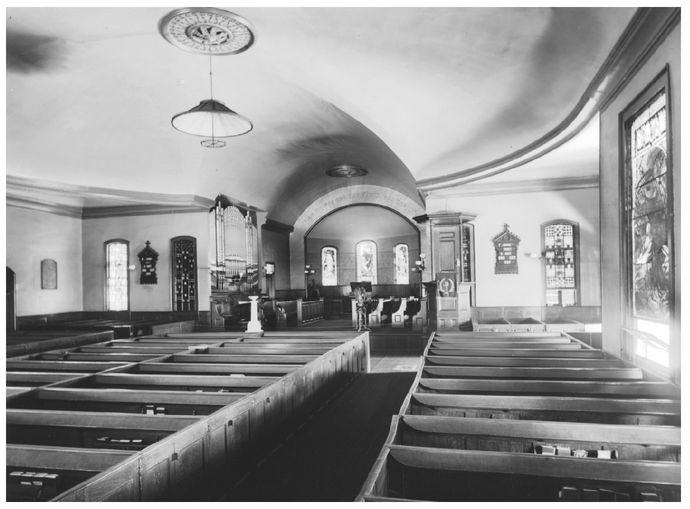

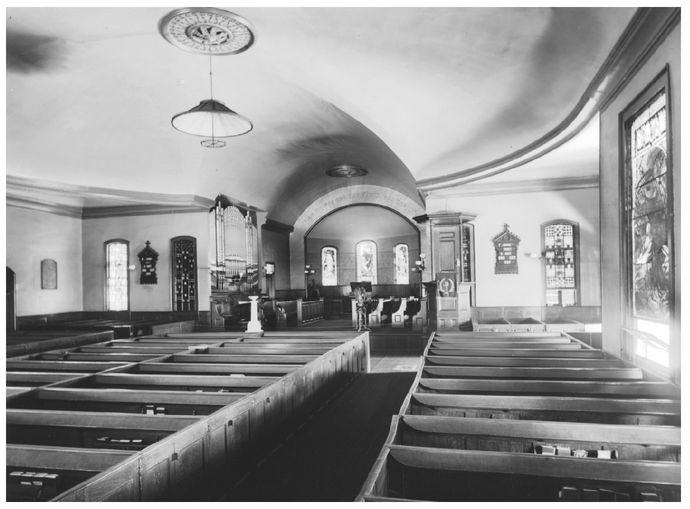

Interior of St. John's Church in Richmond, Virginia, where the Virginia House of Delegates met on March 23, 1775, and heard Patrick Henry deliver his stirring “liberty-or-death” cry for revolution against Britain. Henry stood in the third pew in the left-central section of the assembly.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Â

Give me liberty! . . .

Â

...

the word âliberty' echoed through the building . . . he let his left hand fall powerless to his side and clenched an ivory letter opener in his right hand firmly, as if holding a dagger . . . aimed at his breast. . . .

the word âliberty' echoed through the building . . . he let his left hand fall powerless to his side and clenched an ivory letter opener in his right hand firmly, as if holding a dagger . . . aimed at his breast. . . .

Â

... or give me death.

10

10

Â

...

a blow upon the left breast with the right hand . . . seemed to drive the dagger to the patriot's heart.

11

a blow upon the left breast with the right hand . . . seemed to drive the dagger to the patriot's heart.

11

Other books

One Foot in Eden by Ron Rash

Death By Sunken Treasure (A Hayden Kent Mystery Book 2) by Kait Carson

A Knight's Persuasion by Catherine Kean

The Great Wreck by Stewart, Jack

A Fine Welcome: Othello's Journey by Taran Matharu

Zeus (The God Chronicles) by Solomon, Kamery

Brewer's Tale, The by Brooks, Karen

The Half-Made World by Felix Gilman

Stamboul Train by Graham Greene

Exchange Place by Ciaran Carson