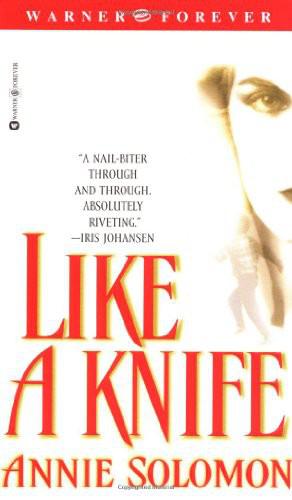

Like a Knife

Authors: Annie Solomon

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Suspense, #General, #Contemporary, #Romantic Suspense Fiction, #Missing Children, #Preschool Teachers, #Children of Murder Victims

"WHAT'S THE MATTER?" SHE TEASED. "CAN'T STAND MY COMPANY?"

"I've got troubles, Rachel. Things I've done. People I've.. .disappointed."

"You haven't disappointed me," she said gently. A rueful feeling shot through him. "Not yet, anyway."

Rachel peered at him, "wondering about the secrets he was hiding. "Everyone sins, Nick. You ask for forgiveness, you make peace with yourself, you move oh."

"There is no forgiveness for some things."

"Then you learn to live with them."

"I'm trying." He gave a short, mocking laugh. "I just can't seem to get the hang of it."

She touched the back of his hand, her common sense gone in a rush of sympathy. "Maybe you need help. A friend."

He looked down at her hand. Her slim fingers rested lightly on top of his, and he was tempted. God, he was so tempted...

If you purchase this book without a cover you should be aware that this book may have been stolen property arid reported as "unsold and destroyed" to the publisher. In such case neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this "stripped' book,"

WARNER BOOKS EDITION Copyright © 2003 by Wylann Solomon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover design and art by Tom Iafuri

Warner Books, Inc.

1271 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com

An AOL Time Warner Company Printed In the United States of America

First Printing: March 2003

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the Tuesday Night Club-Beth, Trish and GayNelle- and to my cyberfriends Linda and Jo. I couldn't have done this without your firiendship and support, not to mention the red ink.

To Becca, for all the lunches and dinners with my many imaginary friends. Finally, you'll get to read about them.

And to Larry, who brainstormed even when he was brain-dead. My rock, my shelter, my love.

I'd like to thank everyone who read the manuscript in its early stages-online and off-particularly Jean Brashear, who offered gracious and continuous encouragement.

Thanks also to all who helped make this book as accurate as possible. To Patricia Hamblin of the, Wilson County Sheriff's Department and to Cassondra Murray and Steve Allen Doyle for the help with guns and weaponry. To Mike Rosen of Kroll Background America for talking to me about background checks. And, finally, to Drs. David Allen and David Schmidt for their medical knowledge and willingness to help with information on wounds and theit aftermath. Any mistakes are my own.

When will redemption come?

When we master the violence that fills our world.

New Union Prayer Book

The duplex stood bald and cramped in the gray morning light. It was barely six, and Rachel Goodman watched the building through the windshield of her car. Her glance swept over the place, taking in the black iron security door that sagged on its hinges and the peeling green paint on the shutters. She sighed a short, determined breath, swung the end of her French braid off her shoulder, and got out of her father's battered VW Beetle.

How would you have handled the Murphys, Dad?

Stupid question. The late, great David Goodman would have made a speech and picketed the place.

Pressing the doorbell, she waited for an answer; when none came, she knocked. She knew they were home. Mr. Murphy worked the night shift and should have only just returned. And there were all those kids. She rapped on the door again and kept it up until she heard the sound of a baby crying and Cecile Murphy's irritated voice from inside.

"Awright, awright. I'm coming, for crissakes. Jesus, who me-" The door opened. The woman in front of Rachel wore a faded nightgown and a shabby bathrobe that didn't quite meet around her swelling middle. She shifted a baby in her amis, not seeming to notice its screams. Another small face peered at Rachel from behind the woman's leg. In the background, the blare of cartoons blended with the sound of children fighting.

"Who are you? It's six in the morning, f' God's sake."

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Murphy. I know it's early, but you haven't returned my phone calls-"

"Shut up!" Cecile shouted over her shoulder. "The both of you! And turn that thing down, Eddie. You wanna wake your father?" She swung back to Rachel and gave her a narrow look. "You're that teacher, aren't you?"

"Yes, I'm Rachel Goodman. Look, could I... could I come in

for a moment? I'd like to talk to you."

Cecile blocked the doorway. "I don't think it would be. such a good idea, Mike-that's Mr. Murphy-he don't want little Carla going to no Catholic school."

"You know it's not a Catholic school. It's in a Catholic church, but I run the school, there are no nuns. It's a special program for children who have been victims of violence, like Carla. Look, your niece has been happy at St Anthony's. She'd just started playing again."

"Well, she's still as dumb as a lamppost."

Rachel reined in her temper. Carla's mother had been stabbed to death in front of the child. How could Rachel explain to this woman what that experience was like? How the white ice of terror froze you up inside? Rachel's own memories surged to the surface, but she pushed them away. "Sometimes it takes a while for kids to speak again. No one knows exactly what happened that night. She doesn't feel safe yet."

Cecile's chin jutted out defiantly. "I got kids of my own who don't go to no fancy school. I don't have money enough for them, why should we spend it on her?"

Of all the selfish, ignorant-Rachel bit down on the words before they could escape. "I can get a grant or a donation. If I can get the fees paid, would you change your mind?"

"We don't take charity. Besides, I got four kids and another on the way. I don't have time to be carting Her Majesty off to some private day care." Without another word, she slammed the door in Rachel's face.

Rachel stared at the door, stunned into immobility. Then she turned to go, shoulders drooping in defeat.

You can't save everyone.

But knowing it in her head and knowing it in her heart were two different things.

She trudged back to her car, fumbled for the keys, and let herself inside. Hands on the steering wheel, she waited a beat to restore her equilibrium before pulling away. Although it was still early, traffic was already thickening. She inched along, reliving the scene with Carla's aunt.

You haven't failed.

Yeah, tell that to Carla.

When she got to Astoria, she shoehorned the ancient Beetle into a parking space a few blocks from St Anthony's. Reaching for her tote bag and purse, she tried to put the morning fiasco behind her. She'd wait a few days, try the Murphys again. Besides, she had other things to think about. Like the letter she'd received yesterday.

Thank you for your grant application, but due to budget cuts we have been forced to turn down some very worthy projects.

God, she was tired of begging. Hadn't she had enough to last a lifetime? First, she'd begged St. Anthony's for free space to house her special preschool, then she'd begged a hodgepodge of charities for grants, next she'd be begging on the street.

She slammed the car door and faced the gritty streets of New York's largest borough. In front of her, a neon sign idiotically blinked open over and over again, even though the gyros place was closed until later in the afternoon. Just like her. Closed but not shut down. Not yet.

She marched the few blocks to the church, past the tiny Greek butcher shop and the discount shoe store on the corner, Mentally, she ticked off all the things she needed. Decent ait supplies, a new playground, a staff psychologist so she wouldn't have to depend on piecemeal volunteers, and most important of all, another home. That was what the grant application had been for-to buy a run-down house she could turn into a permanent home for her preschool. She had six weeks left on her agreement with the church. She tried not to panic, but time was running out.

She thought of one place to go for the money, then quickly dismissed it. Though they were wealthy enough, her aunt and uncle were not exactly supportive of her work with children. Of course, there was always Chris. But even her cousin had never been good at getting his parents to see how important her school was.

She ran around the back of the church and through the gate in the sagging metal fence that enclosed the ramshackle playground. Someday the begging would end. She'd find the money to turn her school into a real institute, a place where every child who experienced violence would have a soothing place to heal.

But right now, all they had was this place. She scanned the woebegone yard, the wobbly picnic bench and half-bald sandbox, the single rusty swing left hanging in the set. She let out a long, slow breath.

One problem at a time. You can't do everything.

Trudging to the yard door, she twisted the knob. Surprisingly, it didn't give. She checked her watch. Six-thirty. She was early, but she'd been early before, and Nick had always been there ahead of her. Ever since he'd replaced the old church, handyman six months ago, Nick had been reliable as the sun. A mystery, but reliable. With a grunt of irritation, she dug in her purse for the key, found it eventually, and opened the door.

She inhaled the smell as she stepped inside. Paste and ringer paint and the peculiar smell that signaled children. The tight ball in her stomach relaxed a bit. Maybe Father Pat would have some emergency fund-raising ideas. Rachel wasn't Catholic, and her children came,from many religious backgrounds, but if Father Pat spoke for her and her program, his voice might be loud enough to drown out Bill Hughes and the other members of the Parish Council who would be glad to see the back of her and her kids. If she could extend their agreement, she'd have time to find another grant.

As she strode down the hall to her office, she noticed the open classroom doors, chairs down from the desks and ready for the day. If Nick wasn't there, who had set up the chairs?

She got her answer when she reached her office and saw him asleep behind her desk.

Terrific, now I'm running a homeless shelter.

But if he needed a place to stay, surely the couch in the church kitchen was far more comfortable than that old, tippy chair.

She leaned against the doorjamb and crossed her arms, watching him sleep. His big, rangy body overwhelmed the rickety executive chair, and for once his face looked serene. The heavy black brows and tough, craggy lines were almost smooth. If Felice and the other teachers could see him now, they'd stop calling him Mr. Hermit. Or the other names they called him behind his back. Creature from the Black Lagoon. Alley Oop. That was because during the first few weeks Nick used any excuse to stay in the basement. If you needed him, you stood at the top of the steps and called down. Up he'd trudge, like a tired dog.

Yet gradually Rachel had come to realize that Nick's one-word replies, the way he looked through, not at you; the way he finished a job quickly and retreated to the basement-it was all part of a calculated strategy to keep his distance. Like a wind-up toy that was never released, everything about him was an expression of tension-his dark unsmiling eyes, the somber set to his mouth. Even his work shirts were always buttoned up tight to the neck.

A dozen times a day she caught him staring at her. Caught herself staring back. She'd had kids like that. Kids who'd had so much trouble in their lives that any-thing

normal seemed strange. Frozen little lumps of ice, they moved only when prodded and spoke only when spoken to. Like Nick, they looked at her as if she wasn't quite real. Underneath, she saw the same longing in Nick she saw in them. Make it real. Make it stay. Make everything all right again.

She sighed. Whatever his troubles, he wasn't a kid, and she didn't need another project. She had enough to worry about without taking on one more needy soul. Setting down her purse, she walked to the desk and saw what hadn't been obvious from the doorway. A thin film of sweat on bis forehead, hands that clutched the chair arms in a death grip, eyes that raced back and forth beneath closed lids.

He was dreaming.

And from his body language, it wasn't a pleasant dream.

Gently, she touched his shoulder. "Nick," she whispered, "Nick, wake up."

The instant her hand touched him, his eyes flew open and he leaped from the chair, knees bent, fists clenched in a fighting stance. Only his rapid breathing broke her stunned silence.

"You... were asleep," she said at last.

He bunked, straightened slowly. She stared at him in astonishment. He swallowed and looked around at the chair as if amazed to find it there. "I'm... God, I'm sorry," he said helplessly.

Rachel waved away the apology. "It's okay, really. I just thought-" She cleared her throat and peered at him, "Are you all right? Do you need a place to stay? I can arrange-" She caught herself, off to the rescue again.

"No, no." He began to inch his way toward the door. "No, I'm fine. I'm just... I had a bad night, and when I couldn't sleep, I... I thought I'd get a jump on things."

'If something is bothering you ... if you want to talk or anything..."

He wiped his mouth with the back of his hand; uneasiness flooded his dark eyes. Clearly he was aching to leave. "I'm fine, really. There's nothing... I'll just"-he gestured over his shoulder with his thumb-"go downstairs."

"If you change your mind-"

He nodded and slid out the door.

In the corridor, Nick banged the back of his head against the wall in an agony of embarrassment. Stupid, stupid, stupid. How could he have fallen asleep like that? And the look on her face. As if it mattered. As if

he

mattered.

He shuddered and tried not to mink about the dream images still shrouding his head: the shadowed Panamanian street, the knife, the small dark eyes that begged for nothing.

He knew why the dream was back. Because she was back. Shelley Spier. Like a ghost, she'd appeared on his doorstep last night, just as he remembered her. Legs incredibly long, skirt short and tight, hair thickly wild. He hadn't asked why she'd come or what she wanted. It was all over her swollen, bloody face'.

"I left him," she said. "Just like you always told me to."

His chest tightened at the memory. Her beautiful face, bruised and battered, her voice pleading with him.

Let me stay here. With you. Just tonight, Nicky. Please.

And he'd said yes. He'd let her wrap her aims around his neck as she'd once wrapped herself around his heart

"I've got something," she said in his ear. 'I've got something Rennie wants real bad."

He didn't ask her what. He didn't want to know. He'd tucked her into his bed and stayed until she fell asleep. Then he left.

Once, he would have headed for the first bar he saw. Last night, he just headed into the street, that nightmare name vibrating inside his head.

Rennie Spier.

Merchant of death and saver of wayward children. Purveyor of guns and plastique. Friend to all the little places with names no one could spell and ancient grievances to war over. Friend to him.

But Nick didn't want to think about Rennie. Instead, he concentrated on the lifeless storefronts, dead in the dark. The Guyana Bakery, L'Abelle Salon, Key Foods. When the stores gave out, he counted parked cars. Duplexes turned into apartments and apartments turned into supports for cloverleafs and overpasses. The highway gave way again to liquor stores, drugstores, and used car lots.

Somehow he'd ended up at St. Anthony's. In Rachel's office. He remembered curling his hands over the arms of her chair, closing his eyes. Her calm, comforting presence had stolen over him, and he'd let it come. But he'd only meant to stay a few minutes. A few dreamless minutes.

"Nick?"

He whirled at the sound of Rachel's voice. She stood in the office doorway, a grown-up tomboy in jeans and a loose, white shirt with the sleeves rolled back at the wrists. Her eyes, the color of new pennies, gazed at him with great kindness.

'There's watermelon for ten o'clock snack. Could you bring it outside and give us a hand cutting it up?"

As always, she'd pulled her honey brown hair into a braid that was already starting to fray. Wisps of hair floated around her neck and face, and he longed to touch them. Instead he shoved his hands into the pockets of his work pants. "Sure." He backed down the hallway toward the basement steps. "Ten o'clock. I'll be there."