Life in a Medieval City (5 page)

Read Life in a Medieval City Online

Authors: Frances Gies,Joseph Gies

Tags: #General, #Juvenile literature, #Castles, #Troyes (France), #Europe, #History, #France, #Troyes, #Courts and Courtiers, #Civilization, #Medieval, #Cities and Towns, #Travel

Near the center of the old city is the Augustinian abbey of St.-Loup, named after the bishop who parleyed with Attila. Originally it lay outside the walls, but following the Viking attack in 891, Abbot Adelerin moved the establishment into the city, St.-Loup’s remains included. The Rue de la Cité, principal street of the old town, separates the abbey from the cathedral, which is at the southeast corner of the enclosure. Workmen are busy on the scaffolding that sheathes the mass of masonry. A huge crane, standing inside the masonry shell, drops its line over the wall. Masons’ lodges and workshops crowd the space between the cathedral and the bishop’s palace.

Near the old donjon is the ghetto. Well-to-do Jewish families live in the Rue de Vieille Rome, just south of the castle wall; farther south, others inhabit the Broce-aux-Juifs, an area enclosed by lanes on four sides.

This is Troyes, an old town but a new city, a feudal and ecclesiastical capital, and major center of the Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages.

A Burgher’s Home

They live very nobly, they wear a king’s clothes, have fine palfreys and horses. When squires go to the east, the burghers remain in their beds; when the squires go get themselves massacred, the burghers go on swimming parties

.

—

RENARD LE CONTREFAIT

a fourteenth-century clerk of Troyes

I

n a thirteenth-century city the houses of rich and poor look more or less alike from the outside. Except for a few of stone, they are all tall timber post-and-beam structures, with a tendency to sag and lean as they get older. In the poor quarters several families inhabit one house. A weaver’s family may be crowded into a single room, where they huddle around a fireplace, hardly better off than the peasants and serfs of the countryside.

A well-to-do burgher family, on the other hand, occupies all four stories of its house, with business premises on the ground floor, living quarters on the second and third, servants’ quarters in the attic, stables and storehouses in the rear. From cellar to attic, the emphasis is on comfort, but it is thirteenth-century comfort, which leaves something to be desired even for the master and mistress.

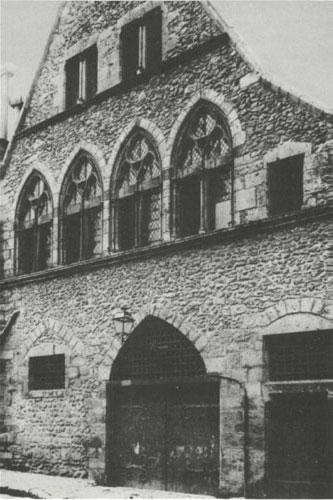

Romanesque house at Cluny

. Several twelfth-and thirteenth-century houses survive in France, in Cluny, Provins, Dol-de-Bretagne, Perigueux, Le Puy, and elsewhere. (Touring-Club de France)

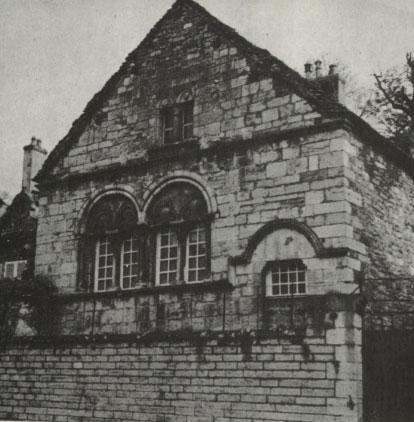

Thirteenth-century house

. No. 6, Rue d’Avril, Cluny, this was the home of a wealthy moneychanger. The irregular stone courses, Romanesque windows, and steeply pitched roof are characteristic of medieval house construction. The brick wall is a modern addition.

Entering the door of such a house, a visitor finds himself in an anteroom. One door leads to a workshop or counting room, a second to a steep flight of stairs. The greater part of the second floor is occupied by the hall, or solar, which serves as both living and dining room. A hearth fire blazes under the hood of a huge chimney. Even in daytime the fire supplies much of the house’s illumination, because the narrow windows are fitted with oiled parchment.

1

Suspended by a chain from the wall is an oil lamp, usually not lighted until full darkness. A housewife also economizes on candles, saving fat for the chandler to convert into a smoky, pungent but serviceable product. Beeswax candles are limited to church and ceremonial use.

The large low-ceilinged room is bare and chilly. Walls are hung with panels of linen cloth, which may be dyed or decorated with embroidery; the day of tapestry will come in another fifty years. Carpets are extremely rare in thirteenth-century Europe; floors are covered with rushes. Furniture consists of benches, a long trestle table which is dismantled after meals, a big wooden cupboard displaying plate and silver, and a low buffet for the pottery and tinware used every day. Cupboards and chests are built on posts, with planks nailed lengthwise to form the sides. In spite of iron bindings, and linen and leather glued inside or out, the planks crack, split and warp. It will be two centuries before someone thinks of joining panels by tongue and groove, or mortise and tenon, so that the wood can expand and contract.

If furniture is drab, costume is not. A burgher and his wife wear linen and wool in bright reds, greens, blues, and yellows, trimmed and lined with fur. Though their garments are similar, differentiation is taking place. A century ago both sexes wore long, loose-fitting tunics and robes that were almost identical. Now men’s clothes are shorter and tighter than women’s, and a man wears an invention of the Middle Ages that has already become a byword for masculinity: trousers, in the form of hose, a tight-fitting combination of breeches and stockings. Over them he wears a long-sleeved tunic, which may be lined with fur, then a sleeveless belted surcoat of fine wool, sometimes with a hood. For outdoors, he wears a mantle fastened at the shoulder with a clasp or chain; although buttons are sometimes used for decoration, the buttonhole has not been invented. (It will be by the end of the century.) His clothes have no pockets, and he must carry money and other belongings in a pouch or purse slung from his belt, or in his sleeves. On his feet are boots with high tops of soft leather.

A woman may wear a tunic with sleeves laced from wrist to elbow, topped by a surcoat caught in at the waist by a belt, with full sleeves that reveal those of the tunic underneath. Her shoes are soft leather, with thin soles. Both sexes wear underclothes—women long linen chemises, men linen undershirts and underdrawers with a cloth belt.

Hair is invariably parted in the middle, a woman’s in two long plaits, which she covers with a white linen wimple, a man’s worn jaw-long, sometimes with bangs, and often topped with a soft cap. Men’s faces are stubbly. Only a rough shave can be achieved with available instruments, and a burgher may visit the barber only once a week.

Wooden casket, thirteenth century

. This ironbound box ornamented with enameled medallions may have held a wealthy burgher’s valuables. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917)

At mealtime a very broad cloth is laid on the trestle table in the solar. To facilitate service, places are set along one side only. On that side the cloth falls to the floor, doubling as a communal napkin. At a festive dinner it sometimes gets changed between courses. Places are set with knives, spoons, and thick slices of day-old bread, which serve as plates for meat. There are several kinds of knives—for cutting meat, slicing bread, opening oysters and nuts—but no forks. Between each two places stands a two-handled bowl, or

écuelle

, which is filled with soup or stew. Two neighbors share the

écuelle

, as well as a winecup and spoon. A large pottery receptacle is used for waste liquids, and a thick chunk of bread with a hole in the middle serves as a salt shaker.

When supper is prepared, a servant blows a horn. Napkins, basins, and pitchers are ready; everyone washes his hands without the aid of soap. Courtesy requires sharing a basin with one’s neighbor.

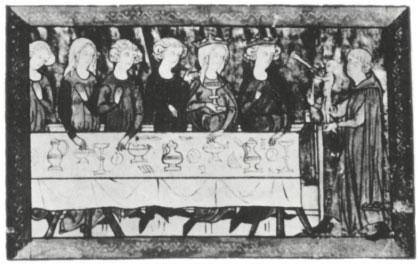

A thirteenth-century banquet

. The scene is from an illuminated manuscript, “The Tale of Meliacin.” A suitor for the hand of the princess displays his gift, a copper figurine that plays a silver trumpet. The guests sit on a bench at a trestle table, each pair sharing a wine cup and an

écuelle

knives and pieces of bread lie on the tablecloth. (Bibliothèque Nationale)

If there is no clergyman present, the youngest member of the family says grace. The guests join in the responses and the amen.

Supper may begin with a capon brewet, half soup, half stew, with the meat served in the bottom of the

écuelle

, broth poured over, and spices dusted on top. The second course is perhaps a porray, a soup of leeks, onions, chitterlings, and ham, cooked in milk, with stock and bread crumbs added. A civet of hare may follow—the meat grilled, then cut up and cooked with onions, vinegar, wine, and spices, again thickened with bread crumbs. Each course is washed down with wine from an earthenware jug. At a really elaborate meal roast meats and other stews and fish dishes follow. The meal may conclude with frumenty (a kind of custard), figs and nuts, wafers and spiced wine.

On a fast day a single meal is served after Vespers. Ordinarily it is sparse, no more than bread, water, and vegetables. However, the faithful are not uniformly austere, and in fact the clergy often find loopholes in the law. In the last century St.-Bernard testily described a fast day at a Cluniac monastery:

Dish after dish is served. It is a fast day for meat, so there are two portions of fish…Everything is so artfully contrived that after four or five courses one still has an appetite…For (to mention nothing else) who can count in how many ways eggs alone are prepared and dressed, how diligently they are broken, beaten to froth, hard-boiled, minced; they come to the table now fried, now roasted, now mixed with other things, now alone…What shall I say of water-drinking, when not even watered wine is admitted? Being monks, we all suffer from poor digestions, and are therefore justified in following the Apostle’s counsel [Use a little wine for thy stomach’s sake]: only the word “little,” which he puts first, we leave out.