Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill (18 page)

Read Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill Online

Authors: Diana Athill

He has never said that he was bullied at school, and he was quite a tough little boy so probably he wasn’t. He was just exiled from all that he most passionately loved, in a place where nothing spoke to him. For a long time I kept two poems he sent me, one from his preparatory school, the other from Wellington, his public school: pathetic, clumsy little poems, one headed BURN THIS AT ONCE and the other NOT TO BE SHOWN TO ANYONE, ‘anyone’ underlined three times. Both were about being in a cold, dark place, dreaming of spring and birdsong and a dewy morning, then waking up and there, still, was the coldness and darkness.

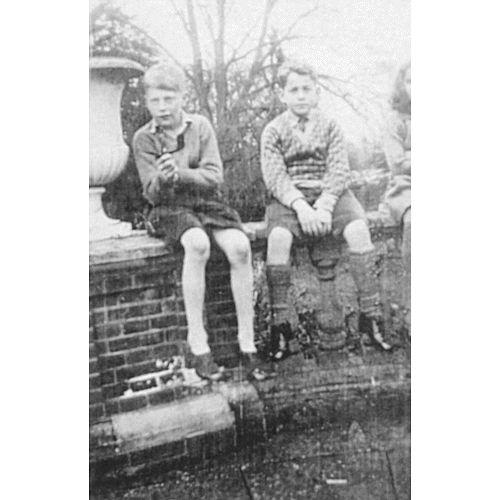

Andrew (with catapult) and John on the terrace

So I knew he was unhappy. But I cannot remember thinking much about it – or feeling much about it, for that matter. Certainly I never questioned his fate: boys had to go to boarding schools, it was what always happened to them, poor things, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. Meanwhile I had my friendships with Pen and with other girls who did lessons with me, I had my ponies, I had my books, I had falling in love … I had moved out of the world I used to share with Andrew, when we busied ourselves together like squirrels or moles in the branches or the roots of adult life. The world I was now inhabiting was quite different. Only years later, when I was in my thirties, did I have a dream which told me how much I had known.

I dreamt that he and I, in high spirits, were running across grass together – and suddenly he was gone. I turned to see what had become of him and there were two men in uniform crouched over something stretched on the ground. Curious, and still happy, I ran back towards them, calling out ‘What have you got there?’ – and it was Andrew. One of the men half-rose and turned towards me, his eyes glaring; the other crouched lower over Andrew, one hand on his throat, the other clamped over his mouth. A scream of horror jolted out of me, waking me, and I lay there hearing my own voice moaning: ‘Poor little boy – oh poor, poor little boy.’

It is easy to see how it worked on him. Having been exiled by the people he had thought to be his infallible protectors, when he was allowed back for limited periods he slid into rejecting them: an exile they had made him so an exile he would be. What had

not

rejected him was the place. He had been sent away from it, but it was still there, waiting for him. So what he did when he came back was burrow as deeply into the place, and stay as far from the family, as he could. It was not an instant or complete process, but gradually it became apparent that his preferred friends were boys from the village, his preferred dress was a smelly old many-pocketed gamekeeper’s waistcoat, his preferred speech was broad Norfolk. At school he did as badly as he could (he would have to spend a year at a crammer before he could get into an agricultural college), and at home he behaved as badly as he dared. Which was sometimes so shamefully badly that it included tormenting a little boy eight years younger than himself.

Our two youngest cousins, Barbara and Colin, never felt as the rest of us did that they belonged to our beloved place. Barbara, with her brother Jimmy, had come for short visits when she was very young indeed, and had then been carried away to India by her parents; and in India the family was tragically stricken: Jimmy fell ill, and died. While we as little children had been wrapped snugly in the fabric of country life in Norfolk, she as a little child had been exposed to a blast of pain beyond our imagining. Her father’s posting as Commander-in-Chief of a district centring on Bangalore still had two years to run, so her parents could not return at once to England. Feeling that they must not risk keeping Barbara and her little brother Colin in India, they first sent Colin and his nanny home to Gran’s house, and about a year later her mother brought Barbara back too, and left her there. It would be for only a year, and where could the children be better cared for?

To a child of seven, ‘only a year’ might as well have been five or ten years; and my grandmother and her resident daughter, an aunt very dear to me, must have suffered some kind of blackout to their imaginations. They were not, of course, positively unkind, but to Barbara they did not seem loving. Perhaps no one could have seemed adequately loving, now that she was so far away from her very loving parents; but I do faintly remember comments about ‘a rather sulky little girl’ which suggest that they failed to understand how deeply unhappy she was – how traumatic Jimmy’s death had been, and how it was possible for ‘home’ to be utterly unlike home to someone very young, lonely and unhappy, to whom it had never been anything of the sort.

When her parents came back they found a house in Dorset which worked a happy spell on Barbara and which she would later remember rather as we remembered Gran’s house. But the latter had acquired unhappy associations. While she and Colin had been parentless there she had known not only loneliness, but anxiety: she had had to protect Colin – or so she felt – from Andrew. No doubt my brother would have protested ‘I was only teasing him’; but teasing is always ambiguous and often masks cruelty (to which that protest can add a nasty little twist), and my sister confirms that at that time Andrew was often ‘really horrid’ to his juniors. I think that ‘tormenting’ was what the ‘teasing’ felt like to the victim and looked like to Barbara.

It was a shock to me when she told me about it, because I never had the least inkling of it. There were eight years between Barbara and me, and only two between me and Andrew, yet I had somehow contrived to ignore his unhappiness, and had been oblivious to the resulting ‘horridness’. The picture it brings to my mind is of chickens pottering contentedly about their run as though nothing were wrong, while in a corner a group of them is pecking all the feathers out of one of their number.

My own theory about the boarding school phenomenon is that it was a reaction by the leisured classes to infantile sexuality. When a young Victorian mother (and my own mother was still Victorian in this respect) gazed fondly at her sweet, innocent baby boy in his nakedness, and suddenly his tiny penis stood up, I think she was horrified. Surely this little being, right at the start of life, couldn’t have anything to do with what men liked to do in bed … but look at it! It clearly had. There, in the male creature, was the old Adam, even now.

So with boys you had to be very careful: however adorable they were, it was not wise to hug or kiss them too much. Some mothers even tried to turn them into girls, but that was obviously wrong – you wanted your little boy to grow up into a manly man, of course you did. But God forbid that the manliness should start before it had to, or that it should get out of hand. So the best thing to do was to isolate boys from the feminine, the sensuous, even before they could fully perceive it – to give them to trainers who would teach them to consume all their energy by

running about

a great deal …

It was not a problem that exercised the working classes, because their sons had to get out there and work as soon as they were out of short pants (or sooner – an old man in our village had been hired out to a farmer by his dad to pick stones off fields when he was eight years old). It arose from having time, as well as space. Of course boarding schools soon became muffled in blah about forming character and training boys to be leaders of men; and of course some families simply found it boring to have unfinished young people underfoot. But ours liked having us there, they wept genuine tears as they sent their little boys away. The imperative at work was a primitive one.

It is extraordinary that the men assented to it even more eagerly than the women. One can only assume that most men, being able to recognize their own sexiness, could easily, if caught young enough, be made to see it as bad; and then found it hard to understand the various kinds of damage done to them by this crude way of suppressing it. Or rather, of trying to suppress it, because naturally it did not succeed. My brother, for one, was to spend a good deal of his youth being far from seemly in his sexual behaviour.

But he did grow up to be a likeable man. He was to become the fond and understanding father of four sons, none of whom he sent to boarding school; and at Christmas lunch in his eightieth year he could look round the table at which sat all those sons, their wives and their children, and make the following pronouncement: ‘At the risk of embarrassing you all horribly, and making my wife very cross, I want to say something. I want to say that

I have never been

happier in all my life than I am today

when I look round this table and see you all here, still wanting to come back to us.’ And when I said to him after lunch: ‘And not only do they all still want to come back, but they’re such an interesting lot, as well as being so nice,’ he looked very sheepish and mumbled: ‘I suppose you could say that Mary and I must have done

something

right’ – which had, indeed, been evident for many years.

The truth is that although there are people who are permanently twisted out of shape as a result of painful childhood experiences, a great many more are not. And my brother is one of them.

F

ALLING IN LOVE

resembled riding, in that it was always there, even before I was aware of it. I can remember being told that I had wanted to marry a boy called John Sherbroke, but not the wanting: all that remains of that boy is a moment of embarrassment when he had come to tea, and Nanny, about to lift him out of his high chair, asked him ‘Do you want to sit down?’ That was her euphemism for using the chamber-pot, and I knew at once from his puzzled expression that in the Sherbroke nursery it must be called something else. Sure enough, he said ‘I

am

sitting down,’ and Nanny was slightly flustered. She had been silly, I thought. She should just have offered him the pot. The first infatuation that I can remember is the one with Denis, the gardener’s boy, which happened when I was about four – or so I believe for reasons given when I described the experience in

Stet

. It took the form of romantic daydreams.

The only daydream material provided by the world came from fairy stories: no newspapers or magazines crossed the threshold of the nursery (Mum’s

Vogue

came later), there was no television, grown-ups didn’t talk to us about love. It was from fairy stories that I formed my notion of what glamour was: a princess. The Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, the many princesses who had to be competed for by princes and who were won by the sons of humble men, that tiresome princess who was kept awake by a pea under a huge pile of mattresses (it was not possible quite to believe in that one): all of them ensured that the companions of Hal and Thomas were princesses, and that it was a princess I was trying to turn into when I called on the magic of dressing-up. But when I fell in love I didn’t dream of myself as a princess being courted: that was too far from reality. Instead I used a different scenario, and where I got it from I do not know … Or didn’t, until I reached this very point, when suddenly a name was spoken in my head: Grace Darling.

Of course it was Grace Darling, the gallant daughter of the lighthouse keeper, rowing her boat through the raging waves to rescue the shipwrecked sailors.

She

came into the nursery: nannies and nursery-maids loved to tell her story, and in some nurseries (not ours, alas) to sing her song. Jessica Mitford wrote a book about Grace and her myth, and could still sing her song with great spirit when I last met her, not long before her death; but I had forgotten her for years and years, until I first heard Jessica mention her. And now I remember her again, because she it must have been who sent me up cliffs, down pits, into burning houses, across flooding rivers, to rescue imperilled Denis, or Wilfred the cowman’s son.

Those were deeply satisfying daydreams, because after the excitement of the rescue came the finale, in which my beloved, recovering from his swoon, opened his eyes and saw me bending over him. At that point Grace Darling retired and a princess took over:

my

princess, the essential me, the one Pen was not allowed to play. The princess with the cloud of night-black hair.

By the time David, recognized by me as my first real love and even acknowledged as such by other people, came on the scene, both Grace and the princess were beginning to fade out. I was eight when his parents rented the Hall Farm for a year:

our

house, because we had lived in it for a while when Dad was abroad (and would return to it when he was working in London). We were staying with Gran when this family of strangers moved in, and Andrew and I, all set for hostilities, crossed the back park and the water meadow on a scouting expedition, to size the invaders up.

David was away at school. It was his younger brother Robin whom we met in the orchard, a small stout figure in a blue coat who turned his back on us to stomp away through the apple trees – shy rather than inimical, as it turned out. We followed him at a distance. When he climbed into one of the very old, half-fallen-down trees, we climbed after him. Whereupon something about him decided us almost at once that he was not a pubby, so we stopped resenting him and he became a friend.