Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill (10 page)

Read Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill Online

Authors: Diana Athill

But not guilty enough to spoil pleasure. The extension of power offered by a pony, the ease and speed of movement, the tapping of unsuspected courage, the satisfaction of collaboration with another creature and of controlling it in order to improve that collaboration, the joy of fussing over it – of loving it – these, from the age of about eight to about sixteen were the most completely realized delights of my life. The smell of a pony was good to me. I would kiss its velvety muzzle with sensuous pleasure, and every shape and texture it offered was familiar and congenial to my hands. There was hardly a movement a horse could make which I could not interpret. A horse will rest a back hoof just to rest it, or again, in a slightly different way, because it needs to urinate. It is uncomfortable for it to urinate if the full weight of its rider is resting on the hollow of its back: the rider should pitch his weight forward onto its withers to allow it the necessary freedom. To see another rider failing to interpret this signal would anger me: how could anyone who rode be so insensitive and inconsiderate? And how could anyone fail to know that his horse was thirsty, or was about to roll, or was being chafed by its girth? The ignorance and stupidity – the

pubbiness

– of anyone who didn’t understand horses was beyond question.

Each animal being different, it was naturally impossible for my relationships with all of them to be equally harmonious. With one it was straightforward friendship, with another a concerned and slightly anxious love because it was too highly strung for its own good. And with Cinders, of course, it was a mock-battle of wills. Even when he was very old, almost as broad as he was long, his blue-roan coat gone frosty grey, he was up to his tricks. I would go out to pass the time of day with him as he dozed under a tree, and he would make a lunge at me; I would slap his nose, laughing, and he would lower his head to present his little furry ears for a rub, apparently knowing it was all a joke as well as I did.

We all anthropomorphized our animals to some extent, but were usually prevented by the attentiveness of our observation from doing it to the point of sentimentality. Indeed, it might be more accurate to say that we came nearer to seeing humans as animals. The study of animal behaviour was not generally recognized as a science at the time – certainly the public was still unaware of its bearing on the study of human behaviour – but when popular books began to be published on its findings I felt that it was all very familiar: it was no news to me that the habits of a vole, a goose or a chimpanzee could be linked with my own.

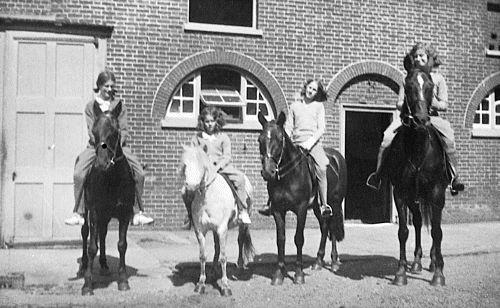

Me on Acoushla; Patience on Patsy; Pen on Zingaro; Anne on Nora, 1928

T

HE HOUSE AND

estate which conditioned our lives and bred our smugness was not, in fact, what we and our cousins felt it to be: a place that had belonged to us ‘for ever’. It had been bought by our great-grandfather, a Yorkshire doctor who had married money, and then was left even more by a grateful patient, a Miss Greenwood. The legacy must have been quite substantial because my grandfather, his only son, was given her name: William Greenwood Carr. And the ‘county’ pleasures of hunting and shooting were not, as they seemed to be, bred into our bones. That same great-grandfather’s parents, whose generation had moved from the yeomanry to the professions (medicine and law), were serious-minded Yorkshire people who believed that the most valuable thing money could buy was education, and had sent their son to Oxford. There, being a lover of horses, he took to riding to hounds. His mother, unpacking for him when he came home at the end of a winter term, found top boots and a pink coat, and was deeply shocked. The young man was told that he had not been sent south to scamper across the countryside with a lot of idle spendthrifts – and was told it so severely that he never rode again, but channelled his love of horses into breeding handsome pairs of them to draw his carriage. Nor did his son, our grandfather, ride, except to jog about his farms. It was our parent’s generation – some of them – who had taken to ‘county’ ways.

My grandfather in his turn would dismay his father while at Oxford, on his part of their climb away from their roots: an incident preserved not by family legend, like the top boots and pink coat, but in four letters in the mass of correspondence kept by my grandmother: four letters which happened to be among those that I read after her death.

Gran’s house, 1920s

They were written in Yorkshire in the late 1870s – my great-grandparents had not yet moved south – and were addressed to their son William at University College. The first was only a few lines – a shot across the bows that must have given Willy a nasty turn – announcing that Papa is so dismayed that he cannot at the moment say anything more: he will be writing at length as soon as he has been able to regain his composure. The second letter explains his shock. Willy had written to say that he had asked for the hand in marriage of Margaret Bright, one of the four daughters of the Master of his college.

On first reading I assumed from the opening lines of this letter that Doctor Carr was outraged because he supposed his son to have fallen for a girl below his station – ‘What a pompous old horror,’ I thought. The tone was too agitated to be just a matter of ‘Don’t be absurd, boy, you are much too young to think of marrying’, which would not have been unreasonable. But I soon saw that I was wrong. Papa was in a panic, and the panic was at the boy’s presumption: he was aghast at what Dr Bright – ‘that distinguished scholar and gentleman’ – must be thinking of the impertinent advantage taken of his hospitality by the boy he had so graciously invited into his house. It had clearly not occurred to Papa that Dr Bright, a widower with four daughters, perhaps made a point of inviting carefully vetted young men to tea as an obvious way to getting his girls married. Instead, Doctor Carr had suddenly and disconcertingly seen his own handsome, intelligent and soon to be well-off son in a new light: as a cheeky clodhopper from the sticks.

The intensity of his panic is made clear by a letter to Willy from his mama, written on the same day, and beginning ‘Oh Willy, Willy, how can you have done this to me’: ‘this’ meaning ‘send Papa into such a dreadful state’ rather than ‘get engaged’. Her letter is one of mind-boggling self-centredness. She is apparently indifferent to the rights or wrongs of Willy’s love affair, and concentrates entirely on what she is having to suffer from Papa’s frantic reaction. She has taken to her bed; she is unable to eat the least morsel of food; her headache is blinding. There is a distinct suggestion of an habitual connivance between mother and son against the father, and what the mother seems to be attempting is a revival of this connivance, regardless of what has caused the trouble.

The fourth letter is also from her, written about a month later. In the interval Dr Bright must have let them know that he is happy about the match, and proposed bringing Margaret to Yorkshire to meet them; and Willy has written to Mama, asking her to be kind to Margaret, who will naturally be feeling nervous. Mama’s answer begins: ‘Dearest Willy, you ask me to be kind to Margaret because she will be feeling nervous. She cannot be nearly so nervous as I will be …’; and goes on for two sides about the suffering that she is bound to undergo.

Her letters persuaded me that there must be a gene for querulous self-absorption. One of her granddaughters was always puzzlingly unlike her siblings in being weepy and self-absorbed. It was a joke in our part of the family that you could safely bet on her bringing any subject whatever round to herself within half a minute. ‘You’ve bought a pair of leather gloves? Oh, how I wish I’d bought leather ones instead of those silly woolly things I got last month …’ As soon as I had read my great-grandmother’s first letter I said to my mother: ‘Good God – this is Aunt D.’

Possibly the plaintive Mrs Carr saw her husband’s agitation as something inflicted on her, rather than as something to share, chiefly because she did not share it. Coming, as she did, from a family richer and higher on the social scale than his, she was unlikely to see the Master’s daughter as beyond her son’s reach. It was she who caused them to move south for her health’s sake, and they would not have been able to buy such a fine house and so much land without her money, so for all her apparent feebleness she carried weight.

The Carrs made the move to Norfolk before my mother was born to Willy and Margaret, but it was not until she was five that the house was inherited by her father, who enlarged it. It was a substantial rectangular house built in the 1730s, overlooking a beautifully landscaped park and lake. My grandfather extended it into a U-shape and added a graceful terrace from which to enjoy the view. He reactivated a nearby kiln which had provided the bricks for the original building, so the new bricks matched perfectly; and because his taste ran to eighteenth-century reading and artefacts, so did the architectural style of his extension. Other newly rich men in East Anglia created mediaeval extravaganzas, but in him there was still much Yorkshire puritanism and common sense, which combined with my grandmother’s academic background to give the family sobriety.

Having read history at Oxford, my grandfather had then turned to law, but he practised as a barrister for only a very short time before coming into his father’s money, which must have been astutely invested – largely, according to my mother, in railways. She told me that he carried on his watch chain a little key, which meant that when the family travelled up to Yorkshire to visit relations they could have the train stopped wherever they wanted. She thought, too, that there was Carr money ‘in that railway across Canada to the Pacific’. My grandfather was a good and businesslike farmer, and for years I assumed that the land was what the family lived on: but there must have been a considerable amount of money in the background, profitably invested, to allow him to enlarge the house so handsomely.

He also enlarged the estate, buying a wood here, a farm there, and when my mother was a little girl she and the sister next to her in age used to be given the job of taking the estate map down from the wall and colouring the new additions pink, ‘like the British Empire’. This was gratifying, but was also seen as a bit of a joke. No fuss was made about it, but in my grandfather’s house it was always in the air that being well-off was no excuse for getting too big for your boots: unseemly or irresponsible behaviour would be condemned as vulgar or (perhaps the family’s most chastening word) silly. I think my grandmother’s love for her William lent a pleasing glow to his background: it was from her I gained the impression that ‘Yorkshireness’ meant sturdiness and honesty. She was proud of the trace of Yorkshire in her husband’s pronunciation of certain words, such as ‘cassle’ for ‘castle’ and ‘larndry’ for ‘laundry’, and her favourite Charlotte Brontë novel was

Shirley

, partly because Shirley was such a spirited young woman, but also because it gave such a good picture of Yorkshire’s industrial development. Her affection for the aspect of the family which was furthest from being ‘county’ probably served as a useful pinch of seasoning in the spell cast over her grandchildren by her house and its surroundings.

Everything important in my life seemed to be a property of that place: the house and the gardens, the fields, woods and waters belonging to it. Beauty belonged to it, and the underlying fierceness which must be accepted with beauty; animals belonged to it, and so did books and all my other pleasures; safety belonged to it, and so did my knowledge of good and evil and my wobbly preference for good. Of course my mother was really more important, but hers was an importance so vital that it belonged inside me, like the essential but unconsidered importance of breathing; and at a pinch the place could stand in even for her, and had once done so.

When I was about a year old my father, then an army officer, was seconded to a frontier commission which was attempting to confirm the boundary between Abyssinia (as Ethiopia then was) and Eritrea. My mother could join him there if she wished to, and to miss such an adventure would clearly have been absurd, particularly since the most baby-loving of my aunts, still unmarried, was living in her parents’ house and would dearly love to take charge of me there for the three or four months my mother would be away.