Life and Laughing: My Story (13 page)

Read Life and Laughing: My Story Online

Authors: Michael McIntyre

When the exams came I had never been more prepared for anything in my short life. Still to this day, I remember most of my results. Maths 78 per cent, Geography 87 per cent, History 82 per cent, Science 83 per cent, French 92 per cent. I came top of the class in every subject. My mum was thrilled (but she was thrilled when I only studied PE and RE), my dad was proud, but the person I was most looking forward to seeing was Mrs Orton. From 4 per cent to 92 per cent, quite an improvement. I sat waiting in the classroom for the French lesson to begin, enjoying my newfound status. I was top of the class. I was a champion.

The teacher walked in, but it wasn’t Mrs Orton. We were told that she had left the school and this new guy, Mr Sissons, was taking over. It transpired that Mr Sissons marked the exams. Mrs Orton was gone, and she was unaware of my dramatic turn-around. I was truly gutted. Where had she gone? Nobody knew. There was a rumour somebody had finally shot her. About ten years later, I was playing tennis in a park when I heard an unmistakable sound from the next court: ‘Shoot!’ I looked over and there she was, planting a forehand volley into the net.

I ran over to her, forgetting I was now nineteen years old and a decade had passed. ‘Mrs Orton,’ I screeched, ‘I got 92 per cent.’ Naturally, she had no recollection of me whatsoever. I apologized and we continued our respective games.

Academically, that was my one good year. I never again worked so hard or scaled those heights. I suppose I just wanted to prove to myself and to my dad I could reach the top, and having done that I slipped back down to the middle. I never again excelled in any subject. I was a bit like Blackburn Rovers when they won the league in 1992. One subject I certainly never excelled in was Music. I am simply not musical in any way. I can barely press ‘play’ on the stereo. My dad, of course, had a musical background and was very keen for me to take up an instrument. More specifically, he wanted me to learn the piano. He owned a piano for me to practise on so he was especially keen for this to be my instrument of choice.

My best friend at the time was Gary Johnson. Gary was tremendously cool. He was a fair-haired American, liked basketball and had his own ‘ghetto blaster’. When my mum asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, he said, ‘Black.’ Gary said guitars were cool, so my mind was made up. The guitar was the only instrument for me. I argued with my dad for hours. The ‘guitar’ row was our biggest to date, and it was only when I threatened divorce that he eventually backed down. He begrudgingly bought me a guitar and booked me in for lessons at my school. Gary said my guitar wasn’t cool – he’d meant electric guitars. So I didn’t attend a single lesson. The guitar sat in my Golders Green bedroom in its case, untouched. My dad didn’t live with us so he would never know. I was now only seeing him every other weekend. He and Holly were as in love as Steve and my mother, and bought a big country house. She had been living in LA and he in London, but they now decided to pursue an English country life together.

Holly dreamed of an idyllic rural life and my dad set about making this dream a reality. The house they bought, Drayton Wood, had 35 acres of land, a swimming pool, a tennis court, stables and two paddocks. They purchased a Range Rover, of course. Kitted themselves out in new wellies and Barbours, and filled their property with two dogs (a Great Dane called Moose and a sheepdog named Benjie), two cats (Marmalade and Turbo), three horses (Nobby, Dancer and Lightning), two cows (Bluebell and Thistle) and six geese (I don’t remember their names), no partridges and several pear trees.

It was a wonderful place for Lucy and me to visit, and they seemed to adjust well, apart from the occasional mishap. The geese, for example, weren’t quite as successful as my father had hoped. ‘Geese are great watchdogs, the best,’ said my dad.

‘What about dogs? Aren’t they the best watchdogs?’ I challenged.

‘No,’ my dad insisted, refusing to follow my logic. ‘Geese are much better watchdogs than dogs.’ So rather than rely on the dogs or indeed install an alarm, he got six geese. On their first night at Drayton Wood, we went to sleep safe in the knowledge the geese would alert us to any unwanted guests by honking. In the morning, we awoke to find six dead geese. My father had forgotten about the food chain. A fox had eaten his new alarm system. It turned out our watchdogs needed watchdogs.

The ill-fated ‘watchdogs’ preparing for their one and only night at Drayton Wood.

Visiting my dad in the countryside was a real adventure. I had horse-riding lessons, rode my BMX, went swimming, played fetch with the dogs and tennis with my dad. It was the perfect weekend getaway. Holly created her dream country kitchen with copper pots hanging from the ceiling and more herbs and spices than I knew existed. She would prepare a variety of dishes with varying success for our juvenile palates. Regardless of how much we enjoyed it, Lucy and I always reported back to our mum that it was ‘disgusting’. Complimenting our new mum’s cooking to our real mum would not have been a wise move.

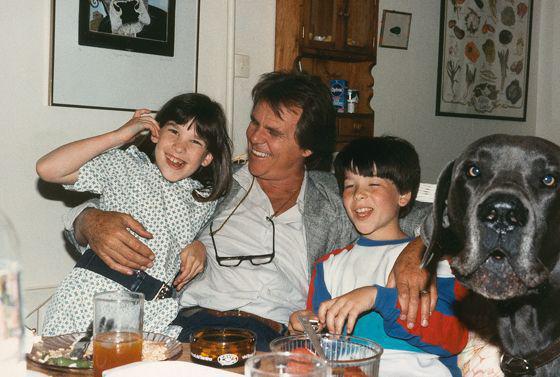

Lucy, Dad, me and our camera-loving Great Dane called Moose at Drayton Wood, my dad’s countryside abode in Hertfordshire.

At one lunch, my dad and Holly had several people over. I don’t recall the occasion. There must have been about ten of us sitting at the large dining room table. My father at the head, telling stories accompanied by his own booming laugh. I was a child surrounded by adults, so the only time I was involved in conversation I was asked typical questions like, ‘What school do you go to?’, ‘Do you enjoy it there?’ and ‘What’s your favourite subject?’

‘Hey, Michael,’ asked my dad, ‘how are your guitar lessons coming along?’

‘You must be a real Jimi Hendrix by now,’ Holly added.

I had been bunking off my guitar lessons for a year at this point. It had actually been so long that I had forgotten I was supposed to be going.

My heartbeat quickened, my voice trembled slightly as I mumbled, ‘Fffine.’

My dad addressed the whole table: ‘Michael begged me to get him a guitar. I wanted him to learn the piano, but he was so adamant.’

‘Adam Ant doesn’t play the guitar,’ interrupted Holly. Everybody laughed at the ‘adamant’ and ‘Adam Ant’ mix-up. I thought maybe I was saved and the conversation would turn to New Romantic pop. I was wrong.

‘What songs can you play?’ asked my dad with a mouthful of Holly’s finest ‘Sloppy Joe’. I was terrified and tried to change the subject.

‘Have you told everybody about the geese? And how you murdered them,’ I suggested.

‘Oh yes, I will. But first I want to know what songs you can play on that guitar I bought you.’

How was I going to get out of this? I had to remain calm, but my heart was nearly beating out of my chest. I flicked my eyes to Lucy, who knew I hadn’t even taken the guitar out of its case. She looked almost as terrified as me.

‘Er-er-eeerm,’ I stuttered.

‘Come on,’ reiterated my dad. ‘You’ve been learning the guitar for a year, what’s your favourite tune?’ All eyes were fixed on me; I felt like throwing up. I couldn’t think of a single piece of music ever written.

‘The …’ I began.

‘The what?’ pushed my dad.

‘The National Anthem,’ I said finally.

The whole table looked confused. A bit of ‘Sloppy Joe’ dribbled out of the side of Lucy’s mouth. ‘The National Anthem?’ said my dad, surprised.

‘That’s very patriotic,’ somebody else interjected.

‘Yes,’ I said, realizing I had some work to do to be convincing, ‘I love it, I just love playing it, I love our country, I love the Queen, I’m really good at it. Aren’t I, Lucy?’

‘Yes,’ Lucy assured everyone. ‘He’s brilliant at it, he plays it all day.’

‘OH MY GAD!’ interrupted Holly in her thick US accent. ‘Cameron, I can’t believe I forgot. I’ve got an old guitar upstairs in one of the boxes, I’m going to go and get it.’

‘What a great idea,’ agreed my father. ‘After lunch Michael can play the National Anthem.’

The blood drained from my body. I was in hell. I wanted the ground (all 35 acres of it) to open up and swallow me. Holly disappeared to look for the guitar. My mind was racing. What was I going to do? Should I feign illness or injury? I was in the midst of a nightmare. My dad began telling his geese manslaughter story. It seemed like only seconds before Holly returned, tuning her old guitar as she walked towards me. My father cut short his anecdote. ‘You found it, great!’ Holly placed the guitar in my trembling hands. The whole table turned to me.

‘Stand up, Michael,’ my father directed.

I stood up, awkwardly holding the alien instrument. This was the moment, the moment I had to admit my lie. The moment to reveal the shameful truth, that I was not so much Jimi Hendrix as the Milli Vanilli of school guitar lessons. I decided to go for it. I don’t even know if I decided. I found myself strumming the guitar and singing, ‘God save our gracious Queen, long live our noble Queen …’ I sang it as loud as I could, to mask the fact that I was just randomly strumming. It sounded horrific; my audience looked puzzled.

‘EVERYBODY!’ I encouraged. ‘God save the Queen, de, de, de, de, Send her victorious …’ Everybody sang along, just about managing to hide my out-of-tune, random guitar-playing. I belted out the last line with lung-bursting pride, like Stuart Pearce at a World Cup: ‘LONG TO REIGN OVER US, GOD SAVE THE … QUEEEEEN … YEAH!’ The most embarrassing moment of my life was over. I took a bow and received uncomfortable applause. It turned out I had fooled nobody, and later that night when the guests had departed, my father took me aside. ‘Michael, I think we need to talk.’

I wasn’t punished for skipping my guitar lessons. My humiliation at lunch was considered punishment enough. Also, my excellent exam results weighed in my favour. I claimed I had been too bogged down with work to learn an instrument.

My dad was pleased with my now glowing school reports. I don’t know why but I was particularly good at Latin. I was a ‘Latin lover’, but not in the sense that pleases women. I was also quite sporty. This might be difficult for you to believe. I opened the batting for the cricket team and was top scorer for the hockey team.

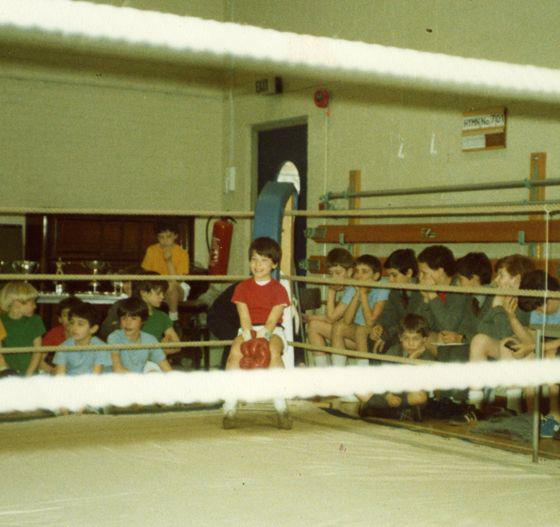

If you think hockey is a bit of a girlie sport, wait until you hear this: my posh private school taught boxing. An ex-boxer, I forget his name, whose face featured the obligatory flat nose, taught us the Queensberry Rules once a week. Fine, you might think. Boxing is good for exercise and co-ordination. Well, at the end of the year a boxing ring was set up in the gym, and there was a tournament when all the parents came to cheer their posh offspring beating the shit out of each other. Come to think of it, with me speaking Latin and boxing in front of a passionate mob, I was like a young Maximus Decimus Meridius in

Gladiator

.

A champion was crowned for every school year. I actually won in the first year, defeating Sam Geddes by a technical knock-out. Sam and I are friends to this day, and I haven’t stopped reminding him of my victory for the past twenty-five years. I’m sure he’ll be thrilled to learn it’s mentioned in my book. I’m sorry, Sam, but the fact is my speed, silky skills and breathtaking power were too much for you. I gave you a boxing lesson. I destroyed you.

In the Arnold House school gym in my boxing prime, about to unleash my silky skills on a helpless Sam Geddes.