Liesl & Po (19 page)

Authors: Lauren Oliver

Will nodded vigorously, and the ghost flickered its agreement. Both were desperately uncomfortable, and unhappy because Liesl was unhappy. Above all, they wished—fervently, more than anything—that a second tear would not follow the first, as neither had any experience with a crying girl.

Only Bundle went to her and wrapped its Essence as close to hers as possible, so that in her soul she felt a comforting warmth. She wiped the tear from her chin with her forearm.

Will felt encouraged to speak again. “Er—it’ll be all right, Liesl,” he said, feeling horribly awkward. “We’ll get there. You’ll see.”

Just then a terrible, shrill scream echoed up through the hills. Liesl gasped and nearly dropped the wooden box. Will jumped, and even Po flashed momentarily to the Other Side, reappearing a second later.

“What was that?” Liesl asked. Instantly she forgot about the difficult way ahead, and the fact that Po and Will had been fighting.

“Sounded like a wolf or something,” Will said uncertainly. He had never actually heard a wolf, but he imagined they would howl like that.

“We must move on,” Po said. “It will be dark soon.”

Liesl climbed heavily to her feet. Every one of her muscles ached. And this time, when Will reached out and said, “Here, let me,” she passed him the box.

“Don’t drop it,” she said.

“Never.”

“Swear?”

He made an X over his heart.

They walked on.

THE TERRIBLE SCREAM THAT HAD SO STARTLED

Liesl and her friends did not come from a wolf.

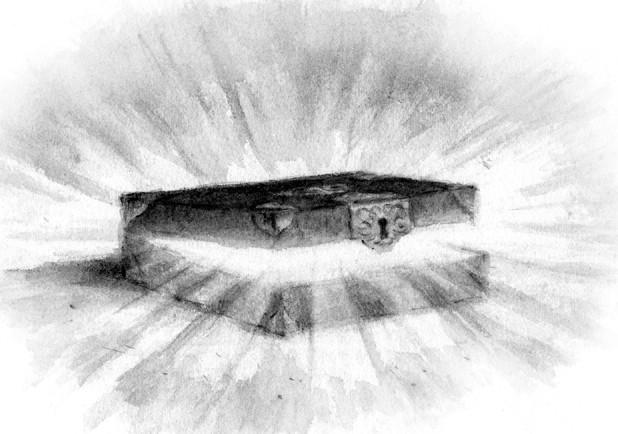

It came from Sticky, who had at that moment—having finally reached an area he felt was sufficiently remote—lowered the wooden box to the ground with eager, trembling fingers, and unlatched it.

How to describe his fury—his outrage—his pure and searing disappointment—when instead of piles of rubies and strands of pearls and little, clinking rings—he had instead beheld a pile of dust, of nothing, of worthlessness? (For so the magic looked to him—like dust.)

There is no way to describe his feelings at that moment. Even

he

could not describe them, which was why, instead, he screamed: a great, long howl, which carried up all the way into the hills.

Had Sticky taken the time to examine the contents of the box more closely, he might have noticed some interesting and unusual features of the substance that, at first glance, appeared to be dust. He might have noticed the very slight way it shimmered, almost as if it was moving and shifting ever so slightly. He might have noticed, too, that from certain angles it appeared to

shine

, just like the long-missing sun, and that it was not a uniform dark gray color, but a hundred different colors all at once—blue and purple and red and green.

But he did not look more closely. Enraged, he drew his leg back and gave the box a quick, hard kick. The box flew several feet and landed heavily with a large crack. Sticky noticed with satisfaction that the latch had broken off and the box had sprung open.

Then something occurred to him: The girl had made a fool of him. She had known, somehow, that he was after the jewelry, and so had replaced it with a box full of dust before sleeping. Yes, yes; it must be so. She believed she could outwit him.

The idea was like a deliverance. The jewelry existed—it

must

exist. The future that Sticky had dreamed of for himself all those years ago was still within reach. (And

how

he would take revenge on that snipe-y, snoopy sister of his once he was rich! He would track her down, wherever she was, and make her pay for every time she had pulled his ears, and pinched his elbows, and called him a worm!)

Sticky remembered that the girl had asked the way to the Red House, and so he set off in that direction. This time, there would be no midnight sneaking. This time, he would have the girl’s riches, even if he had to pry them from her cold, dead fingers.

Sticky smiled.

The magic—now exposed to the air—spilled from the box onto the ground. Slowly, very slowly, encouraged by the wind, it began skipping and spreading over the surface of the world.

EVENTUALLY THE IMPERFECT PATH THAT LIESL,

Will, Po, and Bundle followed began to wind down and out of the hills. The stars were smoldering behind a thin covering of clouds by the time they were at last on flat ground. By then the path had disappeared. All around them were dark, bare fields; and in the distance, a house, with candles burning brightly in its windows.

“That must be Evergreen,” Liesl said. “We’ll rest there for the night.”

Nobody argued. It had been a long, exhausting hike. Even Po was tired—not physically, of course, but from a deep ache in its Essence, from flitting ahead and doubling back all the time, and having to wait for the others to catch up, and keep itself from speaking out when

yet again

Will had to stop and shake a pebble from his too-large shoes.

It was very quiet and very still as they set off across the frost-coated ground toward the house. With every step, Liesl grew happier. Soon they would have soft beds to sleep in, and perhaps a meal. And they were close to the Red House now, she was sure of it—it was only a mile or two beyond the end of the hills. Tomorrow they would finish their journey, and her father’s soul would be at rest. And then . . .

Well, the truth was, she was not sure what would happen then, but she pushed the thought out of her mind. Po would come up with something. Or she and Will would go to work at Snout’s Inn, where the woman had been so kind.

Will, too, felt he could not get to Evergreen fast enough. The box was heavy—Liesl had not lied—and he was so hungry it was painful, as though there were a small animal scrabbling around in his stomach, sticking him with its claws.

When they were thirty feet from the house, Liesl got a last-minute burst of energy and broke into a run. “Come on, Will!” she called. “Almost there!”

Will tried to run and felt a sharp pain in his heel. “Daggit.” He had gotten another stone in his shoe. “Be there in a minute!”

Liesl had already reached the house and was knocking firmly on the door. Will sat down on a large rock, rolled up his pant leg, and wrestled his shoe from his foot, muttering curses as he did.

“Hello,” he heard Liesl say as the front door opened. “We have come from Gainsville. Mrs. Snout said we might find lodging here.”

Dimly, distantly, Will was aware of a large rectangle of light spilling out into the night, and the blurry, dark figure of a person silhouetted within it.

The silhouette crooned, “Of course, dearie, come in, come in!”

Panic shot through Will like a sudden jolt of electricity. All at once he forgot his exhaustion and the pebble in his shoe.

There was something wrong with the voice—something wrong with its sweetness.

It was

too

sweet, like flowers laid over a corpse.

He recognized it.

“Thank you,” Liesl was saying, even as Will found his voice and screamed, “No, Liesl! No!”

Liesl turned, alarmed. But at that moment the Lady Premiere stepped out onto the porch and seized Liesl with both arms, snarling, as she did, “Come here, you nasty little creature!”

“Run, Will!” Liesl screamed as she was dragged backward into the house. “Don’t stop until—”

He did not hear the rest of her sentence. The door swung shut, and there was nothing but silence.

LIESL WOKE UP FEELING AS THOUGH SHE’D BEEN

clubbed over the head—which, in fact, was almost exactly what

had

happened. During her frantic struggles against the Lady Premiere, she had smacked her head against the doorjamb and gone as limp as a lettuce leaf.

The Lady Premiere had thus made two important discoveries:

1. She much preferred children when they were unconscious.

2. The girl did not have the magic, which meant that the boy must have it.

Liesl was lying in a narrow bed in a plain white room. She was quite alone. She did not know what had happened to Bundle or Po, and she shivered a little underneath the thin wool blanket that was covering her.

From beyond the door she heard the muffled sounds of arguing: a man’s voice she did not recognize, and the voice of the woman who had captured her.

“He can’t have gotten far with it,” the man was saying. “It’s dark as pitch outside, and he’s got nowhere to go.”

“Then it should be easy for you to find him and bring him back!” the woman retorted. Liesl heard footsteps, and their voices receded, though she heard the man mutter “useless” several times.

Liesl looked around the room more closely. There was a small oil lamp burning in the corner, a plain wooden table next to the bed, and next to that, a chair. Otherwise the room was empty.

Liesl sat up slowly. As she did, the pain in her head intensified. For a moment she had to sit gripping the edge of the bed and repeating the word

ineffable

over and over.

At last she felt well enough to stand. She did not have to check the door to know that it was locked. Instead she went to the window. Her heart soared as it slid open effortlessly, then her heart immediately plummeted again. She was very high up—on the third or fourth floor, she thought, though it was hard to tell exactly—and the ground below her window was rocky and uneven. The nearest tree was twenty or thirty feet away—too far to reach, or jump to.

She was well and truly trapped, and could only hope Will was on his way to the Red House with the ashes.

She slid the window closed again, momentarily startled by her own image in the glass: Her face and the room behind her were reflected clearly against the backdrop of the darkness outside. She had so often seen herself this way, reflected in the attic window, as she stared out onto the world beyond the glass and fantasized about being a part of it. Now she

was

a part of it, and that girl—the caged girl in the window, stuck onto a pane of glass—seemed almost unrecognizable.