Liberty's Torch: The Great Adventure to Build the Statue of Liberty (20 page)

Read Liberty's Torch: The Great Adventure to Build the Statue of Liberty Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mitchell

Tags: #Itzy, #kickass.to

“Suddenly, at about half past eight o’clock in the evening, a colossal head was discerned through the vault of the Arc de Triomphe, while salvoes of cheering—

‘Vive la Republique!’

—echoed from far down the avenue,” wrote a reporter witnessing the scene.

Liberty swept through Paris, traveling from near Parc Monceau, where the corpses of Bloody Week fertilized the flower beds. She passed by the Arc de Triomphe, where Prussian invaders had marched through the roundabout upon conquering Paris after the siege. She traveled the same streets where the fathers and mothers of those watching, where even the spectators themselves, had fought one French government after another in search of freedom. Some fifteen hundred spectators sang the Marseillaise as she was paraded by.

“It was at once strange and moving to see that, at each turn of the wheels, the head swayed slightly,” the reporter wrote, “as though acknowledging the cheers of the inquisitive crowd. The effect was impressive and, in spite of ourselves, we tipped our hats to return the courtesy.”

The head passed the Spanish pavilion, the humble tents and wagons of the French Society of Succors for the Wounded, the cozy English cottages and the greenhouses lining the Seine. Amid little green folding chairs and low hedges, the head came to rest, and Bartholdi set up his kiosk.

Because Liberty was part of the Paris exposition, Bartholdi was not allowed to charge admission for visitors to enter the statue’s head. Instead he arranged a bold way to raise much-needed money. Any exposition attendee wishing to enter was required to buy a ten-cent picture of New York Harbor at the base. He also set up a souvenir stand where visitors could purchase an embroidered badge depicting the statue. An American newspaper reported in September 1878 that hundreds of visitors climbed into the head every hour. Thousands waited their turn so they could look out through the crown.

Bartholdi had hoped the head would impress Americans enough to goose fundraising from them, but the official review was just as grouchy as Bartholdi’s assessment of American decorative arts in Philadelphia. “Of course a head of such colossal proportions is seen to disadvantage without its proper height, but seen as it is now placed, it seemed rather empty of character and of modeling,” the United States commissioners to the Universal Exposition wrote. “It had the stereotyped frown of the academy. The hair, too, was scarcely expressed at all, except as one rounded mass, and, in a word, it left much to be desired.”

A reporter had turned his attention to the full-scale model in another part of the exhibition. “The straightly thrust up arm is not agreeable, and the action of the figure is strained and theatrical. . . . Whether this figure, made as it is intended, will be solid enough to resist the force of a violent gale when finally placed is a question upon which I do not enter, but it is one which demands most serious consideration.”

That harsh view of Liberty was countered by a reporter reviewing the entire exposition for the

Atlantic

monthly magazine: “The most singular of all is the section of Bartholdi’s Liberty, which is not here a hand, but an enormous head. It is the only thing on a scale with the Exposition. Casting a far-looking, level glance over the whole from its deep-set eyes, it has in its knitted brows a strangely troubled expression, as though it bore the entire burden of responsibility. One is ready to ask, ‘Why did you ever try to hold it?’”

Indeed, Liberty, as crafted by Bartholdi, does indeed look troubled, an evolution from his earlier sketches. In Bartholdi’s earlier renditions, she appeared as a pretty girl hired to hold a torch on a street corner for the day. In some sketches, she seemed almost surprised to find herself with such a task. This Liberty with rounded cheeks was young, but steadfast and filled with a kind of despair.

There is a story that Bartholdi modeled this face after his mother. French senator Jules Bozerian told a roomful of people honoring Bartholdi at a banquet in 1884 that, just before the face of Liberty was exhibited, the senator had met Bartholdi and seen Liberty’s face at the foundry. He had soon after attended the opera with Bartholdi and as they entered the box, the senator noticed a woman already seated there—Bartholdi’s mother. He exclaimed, “Why, there’s your model of the head of Liberty!”

Bartholdi allegedly pressed the senator’s hands and said, “Yes, it is.”

When the senator told the story at the dinner, Bartholdi allegedly teared up.

But Bartholdi never once confirmed that the face of Liberty was indeed that of his mother. When one takes a closer look, Liberty’s face does not resemble his mother at all. His mother bears a striking likeness, oddly, to George Washington, with a thin mouth, aquiline nose, and rounded arches to her light brows. Liberty has a strong, plumper jaw, a troubled brow, a straight, flat bridge of the nose, and a slightly downturned mouth with a full lower lip. Bartholdi possessed an attentive artist’s eye. He often noted the details of faces and he certainly had modeled enough accurate busts of important men.

Bartholdi believed the work should carry the eye to the most important idea of the statue. In Liberty’s case, the most important elements are the torch and the head. Perhaps Jeanne-Émilie served as the model for the body, but someone equally significant would have served for the face. He tended to use people important to him as models for his work, as with the Brattle Street Church frieze in Boston.

In all of his agonizing visits to Vanves, Auguste Bartholdi would have spent a great deal of time staring at Charles. Across from him, hour after hour, Auguste Bartholdi had nothing to do but observe the face of the once-gifted brother he had loved. The face of Bartholdi’s Liberty recalls a photograph taken of Charles in a studio in 1861 where he stands against a fragment of balustrade and blank backdrop.

As with the torch, when it was exhibited in Philadelphia, the head had drained the last of Bartholdi’s funds. The workmen had not started on the trunk of the body, the draperies on the lower legs, nor the arm with the tablet. The trickle of donations had dried up. A new political crisis had been occupying the French public. President MacMahon, the general who had led the Versailles troops in their brutal campaign against the Communards and had been elected in 1873, could not find common ground with the left coalition that had formed in the Assembly. It was a division that led to a stalemate.

Given that distraction, the Franco-American Union could find few people interested in Liberty and sent word to the United States that it might be better for the American Committee to put off working on the pedestal for a year or two until the union could see how things worked out on its end.

Bartholdi did not have the luxury of waiting. He could not afford to occupy the Gaget workshop forever. He needed to complete Liberty and reassure the rather anxious Gaget that he would be moving on. The proprietors would demand their regular monies; soon they would want their space free for other projects. He could not furlough the fifty workers who had labored this long on this very specific work and who expected to be paid.

In presentations about the statue, Bartholdi tended to always portray himself as giving his work on the Liberty project free, as a labor of love. He was often congratulated for that generosity. In fact, Bartholdi had a savvy and ingenious scheme for how he planned to profit from Liberty.

Around the time of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition he had patented the bust of Liberty. On January 2, 1879, he applied to the United States Patent Office to secure Liberty’s entire image. He reserved the right to produce the image in all materials: “This design may be carried out in any manner known to the glyptic art in the form of a statue or statuette, or in alto-relievo or bass-relief, in metal, stone, terra-cotta, plaster-of-Paris or other plastic composition. It may also be carried out pictorially in print from engravings on metal, wood, or stone, or by photographing or otherwise.”

That patent, which was granted at the outset for fourteen years, would allow him to receive monies for any use of his Liberty image, including photographs, as long as he was willing to pursue the collection of those payments. If an American or French company wished to use Liberty in an advertisement, it would have to pay Bartholdi. He could temporarily put the funds collected toward the mounting bills or he could squirrel the money away in his own bank account.

In the spring of 1879, the Franco-American Union in essence surrendered the high road in its effort to motivate the French public to financially support the project. The fund was about two hundred thousand francs short, more than a fifth of the total cost, so the union convinced the French government to hold a national lottery to raise the final funds. By midsummer, even that strategy fell short, so the Ministry of the Interior allowed an extension of the drawing from December 1879 to June 1880—more time for the people to buy tickets. On July 7, 1880, the Franco-American Union received the last funds.

The French had completed their part of the bargain. Bartholdi must have been elated. Now all he needed was to assemble the statue. He had been praised for his forethought regarding all details of its creation. In the article by the journalist who visited the Gaget atelier and spoke with Bartholdi, there is also an account of the reporter’s visit to an art historian to discuss the statue’s significance. The historian discussed how much harder it was to build a colossal sculpture in the modern world. “[The ancients] could dare to do big statues because they had thought out every question belonging to such work,” he commented. “I am not sure that we have done so; we have too much else to think of nowadays.”

Sure enough, Bartholdi had been so busy with the fundraising and marketing and creating the statue’s pieces that he had not yet finalized with Viollet-le-Duc how to make his statue stand on her feet.

The news arrived suddenly. “France has lost one of her most famous sons,” the obituary read. “It would be difficult to mention an artist whose reputation was wider, at least the name of no other French architect was so familiar throughout Europe and America.”

On September 17, 1879, only two months after the French had donated their last funds to finish Liberty, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc died of apoplexy. He had gone to his country house, La Vadette, near Lausanne, Switzerland, and, surrounded by the Alpine scenes he had chosen for the wallpaper there, expired.

A special train for mourners left Paris for Lausanne with about one hundred people on board—architects, delegates from the Paris Town Council (of which Viollet-le-Duc had been a member), his pupils, and friends. In Lausanne, the Parisian mourners were met by Swiss officials, French army officers, military engineers, painters, writers, contractors, sculptors, and most of the town’s citizenry.

Viollet-le-Duc had helped engineer the construction of both Liberty’s torch and her head, which had included light metal support frameworks, but he had left no strategy on how to put the statue on a pedestal and keep her upright against the wind and changing temperatures.

Bartholdi could not very well admit to Evarts and Butler and Grant, nor the fifty men working for him, nor the hundred thousand people around France who had given money to complete his vision, nor the members of Congress who had approved his Bedloe’s Island location, that he hadn’t the foggiest idea of how he was going to get Liberty to her feet.

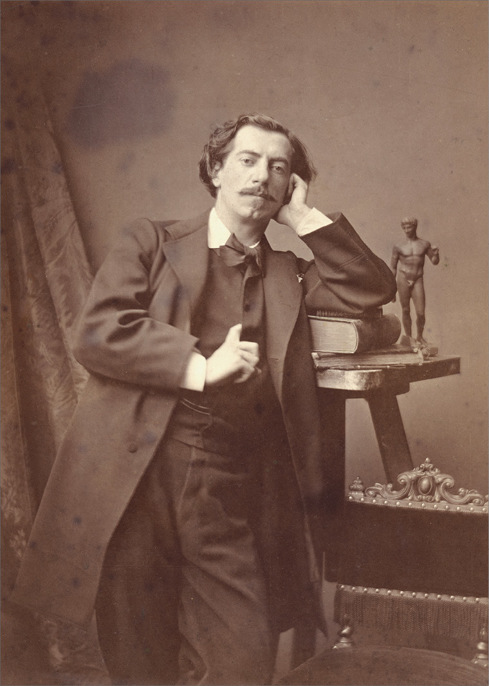

Portrait of the sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (1834–1904).

Credit: Musée Bartholdi, Colmar, reprod. C. Kempf

Charlotte Bartholdi, the artist’s mother, around age eighty. She was widowed when Auguste was two.

Credit: Musée Bartholdi, Colmar, reprod. C. Kempf