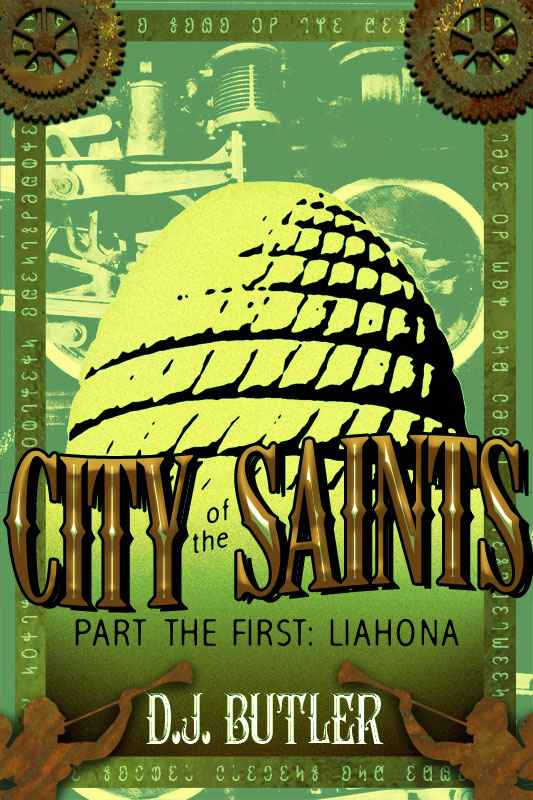

Liahona

Authors: D. J. Butler

Liahona

City of the Saints, Part the First

By D.J. Butler

Cover Art and Design by Nathan Shumate

Copyright 2012 D.J. Butler

Read more about D.J. Butler at

http://davidjohnbutler.com

I worked hard to produce this book.

Pirating this book means stealing from

me; please don’t do it.

City of the Saints

is

an adventure in four parts:

Part the First is

Liahona

.

Part the Second is

Deseret

.

Part the Third is

Timpanogos

.

Part the Fourth is

Teancum

.

If you like

City of the Saints

, you might also enjoy

Rock Band Fights Evil

, my action-horror pulp fiction serial.

Rock Band #1 is

Hellhound

on My Trail

.

Rock Band #2 is

Snake

Handlin’ Man

.

Rock Band #3 is

Crow

Jane

.

Rock Band #4 is

Devil

Sent the Rain

.

Rock Band #5 is

This

World Is Not My Home

.

Chapter One

“This is insubordination, Dick!” the man in the tall top hat

and cravat hissed.

“Well, then, Abby,” Burton growled back at him, “you have

something to write in your little notebook for today.”

“You may address me as

Ambassador

,” the younger, paler man whined, and removed his hat

for a moment to mop sweat from his brow with a white silk handkerchief.

The ceiling of the

Jim

Smiley’s

engine room was high enough for

the two men to stand in comfortably, but the heat that its boiler gave off,

even on a low idle, made the chamber feel smaller and infernal, like a smithy

with the windows all shut.

The heat might make Absalom Fearnley-Standish wilt, but it

wasn’t any kind of serious bother to Burton.

“If we are to stand on rules of address,” he snarled, “you

may call me

Captain Burton

.”

He picked up a heavy tool, spanner at

one end and spike at the other, from a steel crate of similar implements and

hefted it.

He leered at the

diplomat, knowing that the red light coming through the furnace’s grate would

give the scars on both sides of his face a devilish cast.

“This will do well enough.”

“Again I protest,” Fearnley-Standish said, eyes darting

around in the Vulcan gloom.

“My

commission letter says nothing of sabotage.”

“Well, then,” Burton answered in as reasonable a voice as he

could muster, examining the three brass pipes that rose from the iron furnace

to the enormous boiler, “you should have exercised a little more imagination

when you wrote the damned thing.”

With a grunt and a swing of his powerful shoulders, he slammed the spike

end of the tool into one of the pipes.

Clang!

Fearnley-Standish jumped.

Hot air rushed from the hole Burton had made, the room

becoming perceptibly more stifling.

“Egad, stop that!” he spat out, and Burton grinned.

“I find that your inexperience in the dark art of sabotage

comforts me,” he told the younger man.

“It restores my faith in the moral rectitude of Her Majesty’s Foreign

Service.

Moral rectitude, if not

effectiveness.”

He swung

again.

Clang!

“Still,

must do the job right.”

The second pipe was well holed, and Burton looked at the

boiler’s pressure gauge.

Its

needle, already low as the boiler idled, steadily dropped now towards

zero.

Burton was no mechanick, but

he thought that meant he had done the job.

For good measure, he smashed the gauge as well.

“That’s enough!

The Americans will hear us!”

Fearnley-Standish wiped sweat from his face again.

He was trembling.

“I forget,” Burton mused, “how young you are.

You’ve never cut through impenetrable

jungle, never traveled in a foreign country in disguise, never taken a spear to

the face.”

He raised his weapon a

final time.

“Great Kali’s hips,

you’ve probably never even sailed the Nile.”

“Blowhard!” Fearnley-Standish squealed.

“Coward!” Burton retorted.

“Stuffed shirt!”

Clang!

He smashed a hole in the third pipe.

“That should hold them for a day or

two, especially,” he gestured at the crate of spanners and other implements,

“if we take their tools with us.”

Fearnley-Standish stepped away and crossed his arms.

“I’m not carrying those.”

Burton grunted.

“Say something that surprises me,

Ambassador

.”

He

stuffed the spanner back among its fellows and then picked up the box.

“You might, for starters, explain why

you bothered to accompany me on this little sortie.

If you’re so convinced the Americans are not our enemies, or

at least our rivals, you might have saved yourself a little hysterical panting

and remained on the

Liahona

.”

“Did you hear that?” the diplomat hunched his shoulders and

twisted his neck, cupping a hand to one ear while he craned to look up the

stairs that led to the

Jim Smiley’s

deck.

“Pshaw!” Burton dismissed his fears and pushed past,

slipping effortlessly up the iron-grilled steps.

He was nearly forty, he thought proudly, but he was as

muscled as he’d ever been, as strong as he’d been when soldiering in India in

his twenties.

Fearnley-Standish hesitated, and then tapped up the stairs

in Burton’s wake.

“I am Her Majesty’s representative,” he buzzed in Burton’s

ear, “responsible for whatever happens on this expedition.

I couldn’t risk that you might run off

alone and do something foolish.”

Burton laughed harshly.

“Instead, you witnessed the foolishness!”

The deck of the

Jim Smiley

was reminiscent of a sailing ship, a flat space with

a railing around it and cabins fore and aft.

Everything was iron and India rubber.

“I hope you’re taking detailed notes in

your little memorandum-book.”

“Yes, well,” Fearnley-Standish harrumphed.

Something flickered in the corner of Burton’s vision and he

snapped his head around to look at it.

Nothing.

Just a shadow, a

well of darkness thrown into the lee of the

Jim Smiley’s

wheelhouse by the Franklin Poles, the great

crackling blue electric globes standing guard in front of Bridger’s

Saloon.

But was there a darker

shadow within the shadow, a slight stirring?

He stared.

Nothing.

He listened, and

heard the raucous, muffled sounds drifting through the plascrete walls of the

Saloon, but nothing more, nothing that indicated any danger.

The shadow was too small to hide a man

in any case, Burton reassured himself, and he turned and headed for the

rail.

The grated iron floor, the

deck

, since these truck-men all insisted on talking about

their vehicles as if they were sailing ships, jutted out a few extra feet to

the ladder, to get over the strangely rounded and rubber-cloaked hull of the

vessel.

“What is it?” the diplomat asked him.

“Nothing,” Burton dismissed both the other man and his own

fears with one word.

He dropped

the crate of tools to the ground with a rattling

crash!

and slid effortlessly down the ladder after it.

Fearnley-Standish descended more awkwardly.

Halfway down the starchy young man

missed a rung.

He dangled by his

hands for long and flailing seconds before he managed to reattach himself.

“What are you going to do with those?”

he demanded shrilly.

Burton laughed again at the pusillanimity of the other

man.

“I’ll put them in the one

place where Clemens and his goon won’t be able to find them in the morning!” he

cried over his shoulder.

Bending

at the knees to pick up the crate again, he headed across the yard towards the

great shadowy hulk that was the

Liahona

.

*

*

*

“Your road ahead is shadowed and perilous,” muttered the

gypsy.

He held Sam Clemens’s right

hand clutched in his own, which were armored in fingerless black kidskin

gloves, and peered closely at the creases in Sam’s flesh.

Close enough, Sam thought, that the man

could just as easily be

smelling

his future

as

seeing

it.

The man’s hair was long and greasy, as

befitted a gypsy, and his coat and vest were threadbare.

“Your future is one of failure,

disaster and great sorrow.

You

should reconsider your course, sir.

You should turn back.”

The gypsy fell silent and arched an eyebrow at Sam, as if

underscoring the fearfulness of his message.

The silence between the two men was filled with the babble

of the saloon around them.

“That’s refreshing,” Sam quipped, chomping fiercely on his

Cuban cigar.

The air inside

Bridger’s was heavy with smoke, but it was the smoke of cheap American tobacco

rolled into cheap cigarettes, mixed with gas lamp emanations and the occasional

ozone crackle of electricity.

Sam

filtered the stink, as well as the rancid smell of sour, sweaty human bodies

and the drifting odors of horse and coal-fire, through a sweet, expensive

Cohiba.

Nothing, he thought, beats

a government expense account.

The gypsy stared at him.

His gray-streaked black mustache hung asymmetrical under his

bulbous nose, and was no match for Sam’s fine, manly soup-strainer.

His jaw looked misshapen, too, sort of

hunched sideways into the thick, mostly gray, beard that veiled it.

Above all the facial hair and the

badly-cast features, though, the man had dark, intense eyes, with baggy pouches

under them, and those eyes stared at Sam in surprise.

“Did you hear me right, sir?

I told you that your future is bleak.”

“Yes,” Sam acknowledged.

“Your honesty is marvelous.

Most fortune-tellers would take my two bits and tell me what

they thought I wanted to hear.

Beautiful

willing women, rivers of smooth whiskey and horses that run faster than the sun

itself are in your future, sir!

Come again soon.

”

He grinned, took another suck at the

cigar and winked.

“I respect your

integrity.”

And besides, he

thought, you’re most likely right, anyway.

If the Indians don’t kill me, the Mormons will, and that

wily codger Robert Lee must have agents out there somewhere as well.

Failure, disaster and sorrow, indeed.

Sam heard a

clatter

from the corner of the common room.

A squad of Shoshone braves, proud and alien with their beaded vests and

fringed leggings, their strange hair, clumpy on top and then falling long about

their shoulders, and their long magnet-powered Brunel rifles, had shoved aside

several tables and were beginning some sort of coordinated movement that looked

like it might be competitive interactive hopscotch.

They tossed flat disks across the floor and then raced in hopping

motions, each to another man’s disk and then back to his starting

position.

They looked like big,

hairy, dangerous, possibly slightly inebriated versions of little girls.

Sam forced himself to take a second

look at their guns and suppressed an urge to laugh.

Those Brunel rifles hurled bullets faster and farther than

any gunpowder-driven weapon yet made, and punched awful holes right through a

man’s body.

They were English in

design and manufacture, portable railguns, and Sam wondered how the Shoshone

found themselves so well armed.

He

sobered up quickly at the thought.

For that matter, as he looked closer, he spotted electro-knives and

vibro-blades here and there.

Somehow, though it was in a picaresque and highly individualized, even

chaotic, fashion, the Shoshone had gotten themselves serious hand-to-hand

weapons.

Might they have larger

armaments, too?

At this rate, he began to think all the wild talk about

phlogiston guns being tested out in the Rocky Mountains might not be so wild

after all.

Maybe he ought to

consider his mission objectives broader than dealing with Deseret alone, or at

least get that recommendation back to Washington.

It was bad enough that Deseret had air-ships, and might have

ray guns that rained fiery death on their targets.

Once such things got into the hands of the natives, there

might be no end of mischief.

Two of the Saloon’s bouncers, heavy men in buckskins with

knives and guns, didn’t look like they wanted to laugh at all; they moved a

little closer with expressions on their faces that were downright grim.

The gypsy shook his head, perplexed.

What had he said his name was…?

Archer?

He wore a tall boxy beaver hat, a long duster, brown

corduroy pants and a shirt that was striped vertically in purple and gold.

Round smoked glasses that might have

hidden his burning eyes rode low on the onion-like bulge of his nose.

He didn’t really look out of place

here, Sam reflected, surrounded by New Russia Trail pioneers, steam-truck

mechanicks, black Stridermen from President Tubman’s Mexico, cowboys and the

usual clutter of low-life entertainers that filled any bar west of the

Mississippi.

Sam knew that he looked much more at odds with the

environment, in his self-consciously modern attire.

He wore a jacket, without tails because tails were

inconvenient, and white because Sam liked to think of himself as the hero of

the story, even though, if pressed, he wouldn’t admit to believing in

heroes.

He wore Levi-Strauss denim

pants, brand new and shipped straight from the factory to the U.S. Army at

Sam’s request.

They were

comfortable and rugged, and they snapped up the front with a row of metal

buttons for convenience, as well as for a certain masculine flair that shouted

mechanick

.

At

least, that’s what they would have shouted to Sam, if he ever took occasion to

look at another man’s crotch and saw it protected by a row of steel snaps.