Leonardo and the Last Supper (6 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

Andrea del Verrocchio’s

The Baptism of Christ

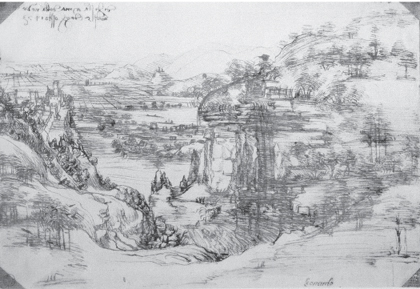

Leonardo appears to have been, in all things, unregimented and independent, willing to disregard fashion, tradition, and precedent. Something else that made him unique was his enthusiasm for depicting the world of nature beyond the bounds of human activity. His first known drawing, done in the summer of 1473, when he was twenty-one, showed an elevated view of the Arno Valley outside Florence: sharp promontories of hill and rock rearing above a plain. The sketch was probably done as a study for the background to a painting, since he seems to have been entrusted with the landscape backdrop in Verrocchio’s

Baptism of Christ

, which features a mass of sheer cliff thrusting upward from a valley floor. The drawing is celebrated as the first landscape in Western art: the first time that someone regarded the features of the natural world, devoid of human presence, worthy of reproduction. Leonardo carefully dated his sketch: “The day of Our Lady of the Snows, 2 August 1473.” On the reverse of the paper he wrote: “

Sono chontento

” (I am happy). In the Tuscan hills, studying rock formations and watching birds of prey rising on thermals, Leonardo may indeed have been the happiest.

27

Leonardo’s first known drawing, of the Arno River Valley

Rocks, like ringlets, fascinated Leonardo. He spent much time tramping around the hills—the hobby mocked by the poet Guidotto Prestinari. This interest in topography was scientific as well as aesthetic. His notes record observations on the layers of soil and rock in the Arno Valley, such as the deposits of gravel near Montelupo, a conglomerate of tufa near Castelfiorentino,

and layers of shells at Colle Gonzoli.

28

His rambles were so famous by the time he lived in Milan that he once received a sack full of geological samples from mountain men: “There is to be seen, in the mountains of Parma and Piacenza,” he wrote, “a multitude of shells and corals full of holes, still sticking to the rocks, and when I was at work on the great horse for Milan, a large sackful of them, which were found thereabout, was brought to me into my workshop by certain peasants.”

29

Such was Leonardo’s reputation, his eccentric pursuits known by the peasants as far away as Parma and Piacenza.

Leonardo was living and presumably still working with Verrocchio in 1476, when he was in his midtwenties. Why he should have lodged with Verrocchio rather than in his father’s more ample accommodation is a mystery, since also sharing Verrocchio’s house were the goldsmith’s scapegrace younger brother, Tommaso, a cloth weaver, and his sister, Margherita, and her three daughters.

30

Had Leonardo fallen out with his father, who following the death of his second wife had recently married for a third time? Ser Piero’s latest bride, Marguerita, was, at the tender age of fifteen, almost a decade younger than Leonardo. In 1476 she gave birth to a boy, Antonio: Ser Piero’s first legitimate child. She would produce five more (including a daughter who died in infancy) before dying in the late 1480s—at which point Ser Piero married for a fourth time and resumed his tally.

Italian literature of the day is full of stories of disputes between fathers and sons. These disputes were a consequence, in part, of a legal system that did not require fathers to emancipate their sons and give them legal rights until they were well into their twenties. The poet and storyteller Franco Sacchetti wrote that “a good many sons desire their father’s death in order to gain their freedom.”

31

Leonardo mentioned this intergenerational battle in a surprisingly churlish letter written many years later to his stepbrother Domenico following the birth of Domenico’s first child—“an event,” wrote Leonardo, pen dripping with condescension, “which I understand has given you great pleasure.” He put something of a dampener on the celebrations with the observation that Domenico was imprudently congratulating himself “on having engendered a vigilant enemy, all of whose energy will be directed toward achieving a freedom he will acquire only on your death.”

32

It is impossible to know how much Leonardo’s sentiments were formed by writers

like Sacchetti—a copy of whose famous collection of stories was in Verrocchio’s workshop—and how much by his own experiences with Ser Piero.

Leonardo probably lived with Verrocchio because he enjoyed the older man’s company. Verrocchio was an intelligent and literate man with sophisticated and wide-ranging interests. Vasari claimed that he studied geometry and the sciences—subjects that appealed to Leonardo—and that he was also a musician. Leonardo, too, was a musician, playing the lyre “with rare execution” and even giving music lessons to pupils.

33

He may even have learned his musical skills from Verrocchio: a lute appears on a list of possessions in the master’s workshop. This list also mentions a Bible, a globe, works by Petrarch and Ovid, and Sacchetti’s book of humorous short stories.

34

All of these sorts of items would later appear in Leonardo’s own studio in Milan, and these possessions are a testament to, among other things, his sustained interest in the intellectual milieu first discovered in Verrocchio’s house and workshop. Indeed, they suggest that the older man, with his manifold pursuits, was Leonardo’s mentor in matters more than just how to grind pigments or hold a stylus. Leonardo arrived in Florence as a country boy from Vinci with only the rudiments of an education. Verrocchio probably smoothed off some of the young man’s rough edges with—perhaps—evenings of recitals on the lute or discussions of Ovid’s poetry.

But the influence no doubt also went deeper. Verrocchio must have been the one who first awakened Leonardo’s interest in things such as geometry, knots, and musical proportions—and their application to artistic design. His tomb slab for Cosimo de’ Medici is a labyrinth of geometrical symbols whose dominant image, a circle within a square, would reappear in Leonardo’s

Vitruvian Man

. Meanwhile the two interlocking rectovals in Verrocchio’s design for the tomb are repeated in one of Leonardo’s ground plans for a church. Verrocchio designed the slab between 1465 and 1467: around the time when Leonardo entered his workshop. It is easy to imagine the young apprentice studying the intricate design and realizing that mathematics was not merely (as he had learned in his abacus school) a tool for commercial transactions but rather a visible expression of the world’s beauty and truth.

Leonardo also seems to have had another home in Florence. Verrocchio’s Medici connections, coupled with Leonardo’s obvious talents, opened the

door on a rare opportunity. The fact that Leonardo lived with and worked for Lorenzo de’ Medici is affirmed by one of Leonardo’s earliest biographers, an anonymous Florentine known (after the Biblioteca Gaddiana, where his manuscript was once kept) as the Anonimo Gaddiano. This manuscript, written in the 1540s, claimed that as a young man Leonardo stayed with Lorenzo the Magnificent, “and with his support he worked in the gardens of his palace in San Marco in Florence.”

35

Lorenzo’s sculpture garden was a kind of informal open-air museum through which he hoped to foster the talents of young artists (the adolescent Michelangelo would be admitted in 1489). Besides ancient statues and bronzes, Lorenzo and his curator, a sculptor named Bertoldo, assembled paintings and drawings by artists such as Brunelleschi, Donatello, Masaccio, and Fra Angelico. What work Leonardo did for Lorenzo in return for his salary is unclear, but he would have been able to make a close study of both ancient statuary and modern works of fame.

Equally important, the sculpture garden gave Leonardo access to Lorenzo the Magnificent, the most powerful man in Florence and a wealthy and astute patron of the arts. Lorenzo was probably at least partly responsible for one of Leonardo’s first independent commissions. Early in 1478 he was chosen by the Signoria, Florence’s ruling council, to paint an altarpiece for the chapel of San Bernardo in the Palazzo della Signoria (now the Palazzo Vecchio). Meanwhile he began several other projects. Toward the end of that year he made a note that he was starting “two Madonna pictures.”

36

The patrons for these Madonnas are unknown, but for another work he had a very important client: he was hired to design a tapestry for King John II of Portugal. Again, Lorenzo or someone in his circle may have helped secure this commission, since King John had connections at the Medici court.

37

Taking as his subject Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Leonardo produced a design that later impressed Vasari: “For diligence and faithfulness to nature,” he wrote, “nothing could be more inspired or perfect.”

38

At some point in the 1470s, Leonardo found work with the affluent Benci family, executing a portrait of a young woman, Ginevra de’ Benci. Ser Piero served as the Benci clan’s legal trustee, but Leonardo’s Medici connections no doubt also helped secure this portrait commission, since Ginevra’s father and grandfather both had been managers of the Medici bank, and Lorenzo himself composed sonnets in Ginevra’s honor.

39

The man who probably commissioned the work, though, was the Venetian diplomat Bernardo Bembo, who

during two embassies in Florence in the 1470s established a close relationship with Lorenzo de’ Medici and an even closer one, apparently, with Ginevra.

Another commission came Leonardo’s way in July 1481 when he was hired to paint an Adoration of the Magi for the Augustinian church of San Donato a Scopeto, outside the gates of Florence. Ser Piero no doubt played a vital role in securing the commission since he was the notary for the monks of San Donato a Scopeto. However, the contract for the altarpiece was a strange and complex one for which Leonardo may not have thanked his father. It stipulated that Leonardo should complete the altarpiece within two years, or at most in thirty months; if he failed to deliver, the monks reserved the right to terminate the contract without compensation and take possession of the work, such as it might be. His remuneration was a one-third share in a small property outside Florence originally owned by a saddle maker, the father of one of the monks. Oddly, he was also obliged to provide from his share of the property a dowry for the saddle maker’s granddaughter, a seamstress named Lisabetta.

40